Spotlight on Alex Garland: sci-fi’s consistently brilliant ideas man

Some find his work distant, others are put off by its intensity; but there’s no denying Alex Garland’s storytelling has a tangible effect on his audience. Rory Doherty chooses five of the Men director’s essential works.

Alex Garland first snuck into Hollywood when his eco-utopian book The Beach was adapted by Danny Boyle and his frequent screenwriting collaborator John Hodge. It wasn’t before long that Garland himself became a Boyle collaborator, and so started the career of one of Britain’s most identifiably uncanny but persistently human writers.

Garland’s career can be split into three sections; his three Boyle collabs, his work as a producer and screenwriter (where he also wrote for video-games), and his work as a director of his own scripts, a journey that continues with this month’s Men. His work gets richer with every script he writes, and having directorial control only strengthens the uneasy, melancholic, and intellectual strangeness he wants to pervade his fictional worlds.

Sunshine (2007)

After debuting with the more intense zombie-but-not-zombie horror 28 Days Later, Garland would work closely with Danny Boyle for another rewarding sci-fi tale. A scientific team is sent into space with a bomb big enough to reignite our dying sun, but they find their journey haunted by a team that attempted the mission before them.

The thriller’s reach does at times extend further than its grasp (a result of the years of overhauling and refining the story), but Sunshine’s approach to existential and philosophical ideas and tendency to go operatic make it stand out amongst contemporary space fare.

Dredd (2012)

According to longstanding rumours (and Karl Urban saying it out loud), Alex Garland didn’t just pen this adaptation of the iconic British comic character—he directed it too. Set nearly entirely in a dystopian tower block where fascistic cops administer judgement and punishment on the spot, the helmeted, growling officer Dredd finds himself trapped with a rookie and an army of gang members.

The fight to topple one drug dealer is as gruesome and pulpy as you can imagine. A uniquely unintelligent offering from Garland, Dredd is outlandish, stylised fun, with some gleefully excessive bloodshed in a finely-detailed futurescape.

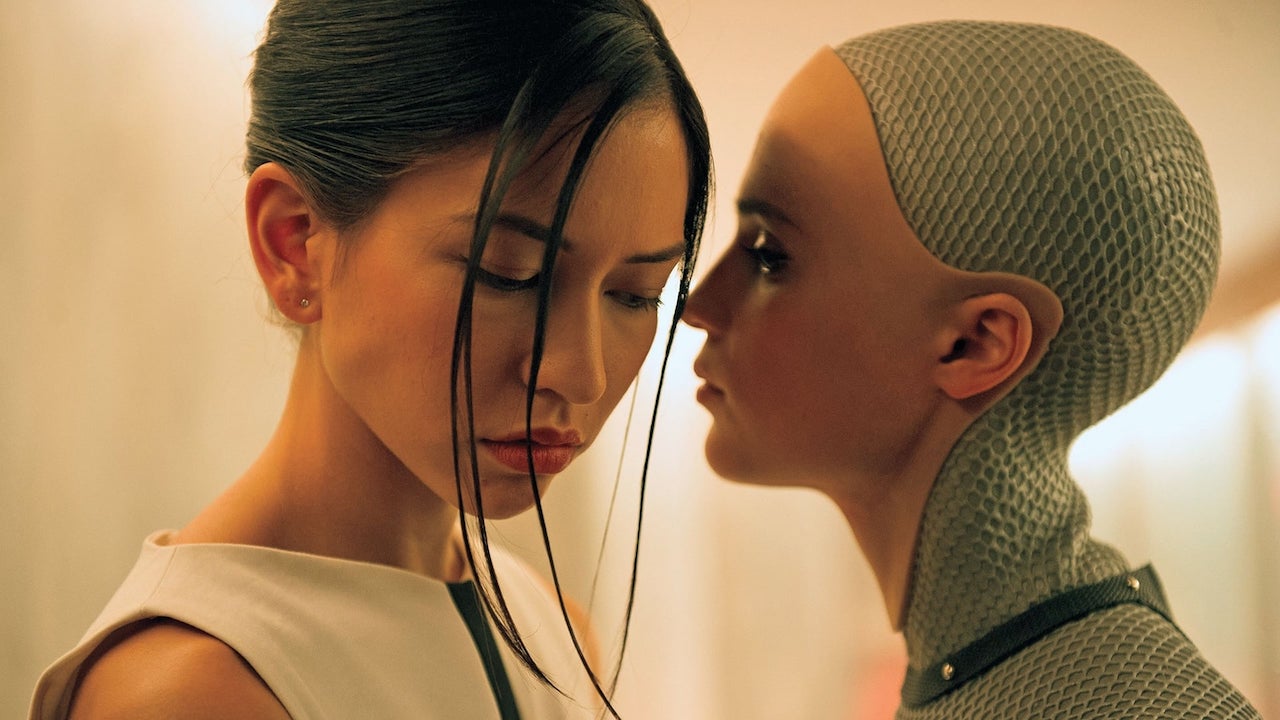

Ex Machina (2014)

After a couple book adaptations and four screenplays helmed by other directors, Garland made his official directorial debut with a low-key sci-fi thriller that blew everything that came before out of the water. A deft, intense three-hander oozing with polished style, it sees a bro-ish tech pioneer using one of his nobody employees to test a newly created android’s artificial intelligence.

Locked up in the pioneer’s ultra-modern, ultra-reclusive compound, secrets start to be revealed and loyalties become twisted. Gripping throughout, the film also presents complex gender dynamics and a formidable explanation of why “mimicking humans” shouldn’t necessarily be the ultimate goal for artificial life.

Annihilation (2018)

It’s a mythic voyage into the unknown, it’s an uncomfortable reflection of the self, it’s a submission to chaos; Annihilation is unquestionably Garland’s most powerful and perplexing film. When a meteor crash starts impossibly affecting a coastline’s ecology, a secretive faction’s mission threatens to unpick the humanity of every one of its female team members.

But the weird and eerie permeate Annihilation long before its protagonists immerse themselves in the mutating biosphere. It underperformed in the US (releasing exclusively on Netflix in the UK), but for eager viewers, Annihilation serves as a potent rumination on how the fantastical can symbolise our own very real undoing.

Devs (2020)

Those promised a tech conspiracy thriller would undoubtedly be disappointed with his foray into television, but Garland’s miniseries about grief colliding with quantum computing and the illusion of free will is an ambitious and multi-pronged exploration of topics that would make even the most seasoned of writers feel hopelessly intimidated.

Sonoya Mizuno, who appeared in Garland’s prior two films in non-speaking roles, takes centre stage as the reeling, overwhelmed Lily—she’s surrounded by an imposing and commanding ensemble whose personal struggles blend with massive, looming sci-fi ideas. With a filmography as confident as this, it’s incredibly exciting to think what Garland will offer us next.