Seen That? Watch This: 3 superhero comedies better than Thor: Love and Thunder

Seen That? Watch This is a new weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release—here, Thor: Love and Thunder—and matching it to comparable, superior works, creating the ultimate cinephile homework assignment.

Thor: Love and Thunder

To take stock of where we are, MCU-wise: we’re up to Spider-Man 47, several dozen Doctor Strange movies, the fourth or fifth Endgame, and a handful of Thors. Maybe I got those numbers slightly wrong, but who can keep up? Love and Thunder is Taika Waititi’s second outing led by Chris Hemsworth’s beefcake hammer-wielding hero, of that much I am sure, thrusting him into another save-the-world narrative—this time involving a pasty-faced Christian Bale on a mission to destroy all gods.

Bale’s villain Gorr gets a good opener: scabby and rakishly thin, he stumbles across a desert into an oasis to meet the god he’s devoted to—only to discover this divine being is a total dick. Therefore Gorr—not unreasonably—declares “all gods will die.” The script plays into the idea of legend, with the rock-like Korg (Waititi) delivering campfire narration recounting the adventures of the titular “space viking.” This would’ve provided a clear narrative framing, but clarity (and narrative) is not one of the film’s features. It doesn’t take long for proceedings to get disorderly in that very orderly, box-ticking MCU way, rehashing the usual elements i.e. battlefields with creamy skylines, blandly choreographed bling-filled fight sequences, and turgid dialogue.

Thor and his ex-girlfriend Jane Foster (Natalie Portman) have the gall to lecture us about mortal virtue, by way of Hallmark dialogue: “I choose love”, says the former; “keep your heart open”, soapboxes the latter. The drama is pure flapdoodle, but Waititi brandishes a couple of effective comedic weapons: one a pair of screaming goats, the other a very amusing performance (with a weird Greek accent) from Russell Crowe as Zeus. In comedic terms, Waititi has taken Love and Thunder about as far as the studio bigwigs will allow; in the MCU artists are relegated to middle management.

It doesn’t have to be like that. Below are three examples of superior superhero comedies that don’t just tell jokes from within their narrative worlds, but alter their very form and presentation to make those gags sizzle.

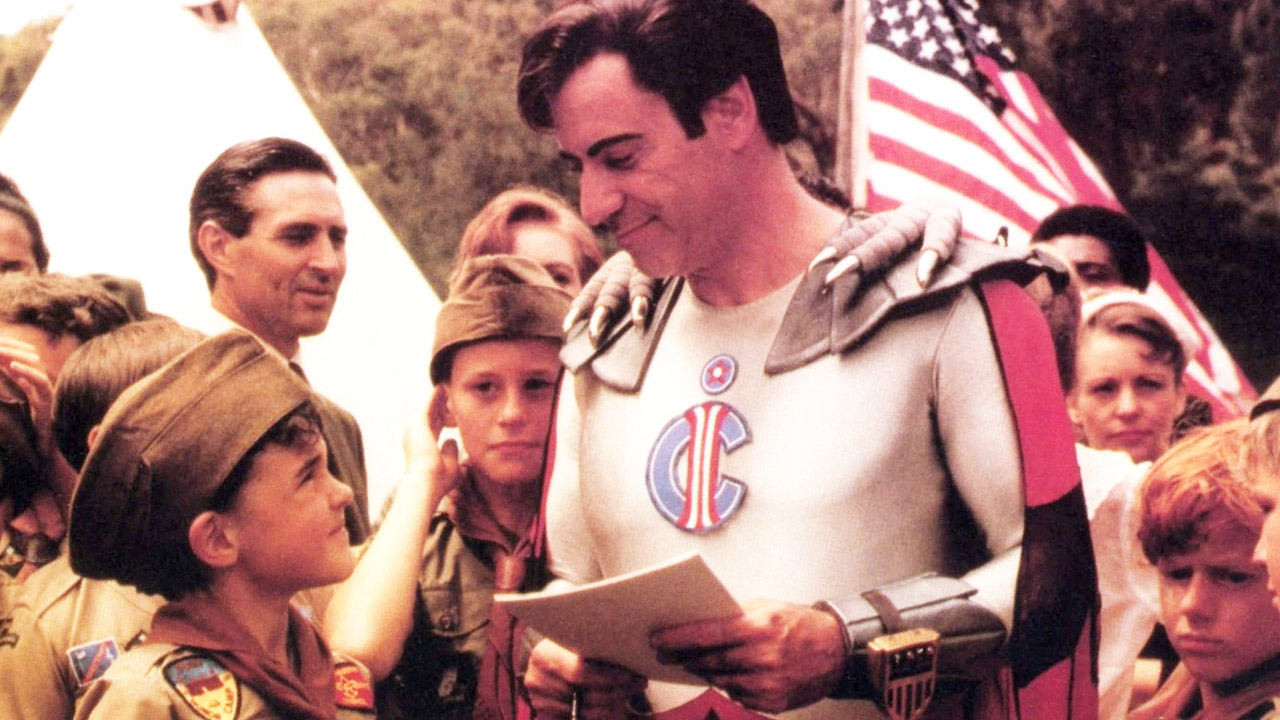

The Return of Captain Invincible (1983)

Philippe Mora’s Ozploitation comedy inventively carved out a now-familiar space: the postmodern superhero movie that cynically deconstructs the genre while still delivering goodies-v-baddies spectacle, with a terribly flawed protagonist. Several comparable films now exist (see Watchmen, The Incredibles, Kick-Ass, Hancock) but none have matched its strange exuberance. Alan Arkin’s titular character begins flying high—busting bootleggers and fighting Nazis—but falls out of favour with U.S. authorities, prosecuted for violating airspace and wearing undies in public.

The disgraced Cap buggers off to Australia, where he becomes a hopeless drunk singing sad songs about a rapidly changing world. The film is also a musical, because why not—particularly when the songwriter is The Rocky Horror Picture Show’s Richard O’Brien. When Captain Invincible’s nemesis (Christopher Lee) steals a devastatingly powerful “hypno ray”, guess which over-the-hill former hero the American government turns to in their hour of need?

It’s one of those “there are no words” and “what were they thinking” oddballs—with a scratchy, endearingly unconventional quality. One scene that always stuck in my mind, depicting the now-flabby protagonist practicing how to fly again, is weirdly layered in a way that makes you wonder whether Mora is trying to say something or just feeling around in the dark. The Cap practices flying in front of a blue screen, while a wind machine blows on him. It’s a genuine attempt to get him used to sailing through the sky again—as well as a commentary on media simulations and constructs.

Super (2011)

Rainn Wilson’s weirdo schtick, finessed in The Office, gets a good workout in a film that plays the concept of copycat superheroes for nasty laughs. Wilson’s Frank is a schlub who, when Kevin Bacon’s smarmy drug dealer lures his recovering wife (Liv Tyler) away from him, snaps and starts clobbering people with a monkey wrench while dressed in a goofy homemade costume. Coining his own catch phrase (“shut up, crime!”) and targeting, along with Bacon’s goons, scumbags who cut in line at the movies, the humour is black as black can be, with intense zest and playfulness.

There isn’t much room in the MCU, as the Thor movies demonstrate, for self-conscious comedy: the universe’s internal logic is sacrosanct. But in Super nothing is written in stone and there are no moral assurances—even that good and evil exist in the first place. Gunn tosses around wacky visual embellishments that confuse distinctions between realism and comic book fantasy. One takes place literally inside the protagonist’s head: as Frank contemplates opening his door, we see illustrations of a possible future unfold inside a cartoon thought bubble.

This deranged protagonist is clearly deeply unwell (see also: Kick-Ass and Griff the Invisible), inspired by, of all things, a dodgy production on a Christian cable TV channel. Is Gunn deliberately drawing a line all the way back to the bible as the ultimate foundation of the genre—with Jesus the original superhero? Could The Ten Commandments be another way of saying “shut up, crime!”?

Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie (2017)

“This whole visual storytelling thing is hard”, says a character in David Soren’s gloriously kiddish pastiche. This reflects the director’s attitude: keep moving, keep poking every scene for opportunities, keep shifting realities. The core of the film is a childhood fantasy: two young kids—George (voice of Kevin Hart) and Harold (voice of Thomas Middleditch)—get complete mind control of their malevolent principal. Said principle becomes a superhero (at the characters’ beck and call) with a difference: indestructible, idiotic, and undie-flinging.

The film begins as a series of scribbled down pictures, before introducing its root reality. An hour in, it morphs into the style of a flip book. Fourteen minutes in, the closing credits appear, the boys unsuccessfully attempting to trigger the end of their own movie. Seventeen minutes in a segment is acted with puppets—and on we go. Soren works a little too hard, intentionally dislocating the narrative and scrambling the rhythm, but that’s a refreshing criticism to make.

Once the mean ol’ principal has been neutered, an actual villain is required. Enter Professor Pee-Pee Diarrheastein Poopypants Esq: a science teacher embittered by the cruel laughter aroused by his surname, and apparently unaware of his ability to legally change it. Ergo, he launches a nefarious plan to transform the kids into humourless subservients using a special ray gun. We don’t need to recount the narrative logic allowing him to do this; more pertinent is the point that the film is energetic. Very energetic.