Innocence lost: the traumatising sound and sights of indie horror Skinamarink

Now screening in very, very select cinemas and headed to Shudder soon, the buzzworthy indie horror Skinamarink gave Eliza Janssen a severe case of the heebie-jeebies. Here’s why its analog childhood terror is worth experiencing.

After dark, I still skirt my way to the bathroom from my bedroom with my back to the wall: still ensure that my feet are safely under the covers. It’s pretty childish, sure, but as a kid who grew up with an obsessive fear and curiosity of horror movies, some boogeymen never leave you.

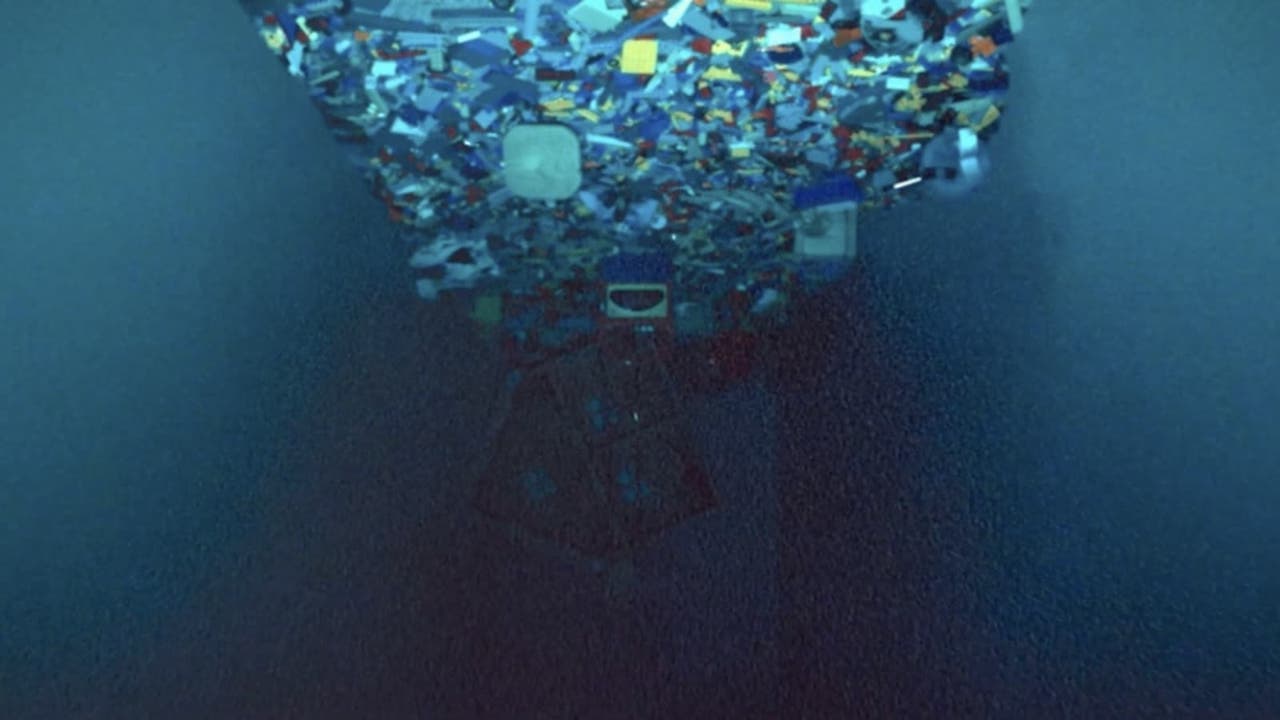

I have a feeling most viewers of Skinamarink, the first fuzzy, confusing feature by US director Kyle Edward Ball, will be transported back to that vulnerable young state too. With its crowdfunded budget of just $15k and shooting location of Ball’s own childhood home in Canada, the movie makes its meagre budget a feature rather than a bug. The sound design is oppressive, Eraserhead-esque, and lower-case subtitles don’t always appear to clarify what the home’s entities are whispering to us.

With notes of found footage or Sinister’s sinister video tapes, Skinamarink reaches out with a chubby little hand and drags us around a darkened home, never clearly showing the faces of child protagonists Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault). They’re heard or felt much more than seen, as are their ghostly parents.

Anyone particularly triggered by imagery of neglect or, as the film obliquely suggests, child abuse should absolutely steer clear, as the two minors’ fragile optimism is obviously headed to an infernal and existentially terrifying end. Even as their food (mostly sugary cereal) runs out and the comforting static of old-fashioned cartoons on the TV itself turns scary, they’re always certain that mum and dad could show up to make everything better.

The film has drawn rightful comparisons to Mark Z. Danielewski’s ergodic novel House of Leaves, a horror story which requires the reader to interpret complex footnotes and strange arrangements of text for the sole purpose of building a claustrophobic, liminal atmosphere. Right from its never-referenced title, Skinamarink accomplishes the same bewildering sense of the viewer being completely as lost as its hopeless characters.

You might recognise the nonsense word from a preschool song of the 1910s (you know, one of those bops) that goes “skinamarink-a-dinky-dink, skinamarinky-doo, I love you”—but why the hell does the word skin feature so heavily, in such a trivial and cutesy children’s ditty?

As an aesthetic experience rather than the sophisticated “prestige horror” we’ve come to expect lately, Skinamarink is utterly terrifying. One particular sequence that had me watching through my fingers sees Kaylee beckoned up to her parents’ bedroom, where they or things that look eerily like them are sitting and sobbing on the bed.

The mother’s distorted voice urges her to look under the bed and oh fuck she does, a few times, not finding anything at all but raising every hair on the viewer’s traumatised bodies. When the inevitable jumpscare moment does come, it’s nothing special—but ingenious sound design will still shatter you.

I hope that even viewers with Kevin and Kaylee’s distracted attention spans will feel hypnotised by the film’s void-like vibes: the analog hissing and humming creates a palpable dread that’s only reinforced by its sudden absence, in the third act’s surreal silence. The fact that Ball dares to create such traumatising sounds and visions in the home in which he grew up, with his own retro plastic toys haunting a new set of babes in the purgatorial woods, makes all the abstract horror that much more visceral.

We’ve all been confused little people, bathing in the protective light of TV and our favourite nightlight as the grown-ups meant to protect us are nowhere to be seen: for 100 agonising minutes, Skinamarink sits us right back in that unforgettable, helpless state.