I Used to be Normal: A Boyband Fangirl Story can’t let go of its desire for cred with the cool kids

What to make of a film like I Used to be Normal: A Boyband Fangirl Story? A documentary that doesn’t appear to want to make fun of its subjects and yet is made in such a way that laughter from the audience is all but inevitable.

Let’s face it, people have been primarily conditioned to find feminine cultural tastes inherently inferior. Pop music in the form that we know it today is widely considered the domain of young girls (and queer men, but the film doesn’t go there so let’s avoid it too) who simply don’t know any better and who just haven’t discovered rock and/or more transgressive artists. It’s not to be taken seriously and thus neither are its devotees.

I Used to be Normal is about four such devotees: Dara from Sydney, Susan of Melbourne, Sadia in San Francisco, and Elif, the youngest of the four, still a teenager, from Long Island. They each share an obsession with a specific boyband that goes beyond what most people would consider “normal”. Australian filmmaker Jessica Leski tells their stories in this energetically if frustratingly assembled documentary.

Pop music, of course, has been a staple of the music documentary. The sheer world-dominating class of Madonna both on stage and off is what makes Madonna: Truth or Dare perhaps the greatest music documentary ever made, and the ability to challenge conceptions of vacuousness and emptiness while embracing the joyousness of pop spectacle allowed the more recent likes of Katy Perry: Part of Me and Justin Bieber: Never Say Never to succeed despite what one may think of the music at their centre. But these films often struggle to gain acceptance without qualifiers.

This perception that people who like pop music are somehow being conned by the gloss and the shine and the pretty lights is at the heart of I Used to be Normal. Amid festival audiences looking for ironic lulz, Leski attempts to persuade that pop isn’t just a tween’s game by observing her four subjects with an often-respectful tenderness that is a refreshing counter to the attitudes they often receive from friends, family and strangers in the real world. Her film dives into their lives and reveals the struggles of being somebody whose entire being is connected to something the world perceives as trivial and just a youthful excursion of frivolity. Not because they don’t find fulfillment in their fandom, but because society tells them they shouldn’t.

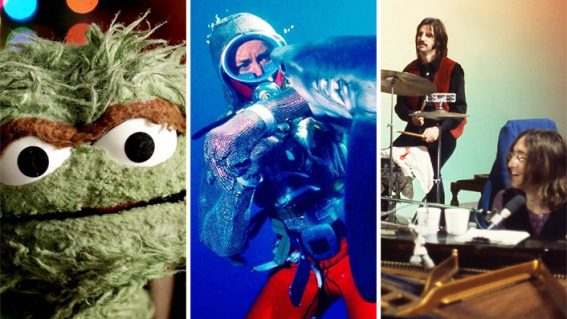

We hear about how Sadia’s love for the Backstreet Boys was an antidote to her strict Muslim upbringing, but has struggled to translate that devotion into adulthood. The two most seemingly well-adjusted are the Australian subjects, with Sydneysider Dara detailing how her all-consuming love for British pop group Take That allowed her to come to terms with her own reality as a same-sex attracted woman whose affinity for lead singer Gary Barlow wasn’t a mere teenage crush. Meanwhile, Susan’s history of Beatle-mania is suggested as a reaction to the changing times of the 1960s and as a means of young women to express themselves and their growing independence.

Now, to be fair, its subjects are clearly more ensconced in the world of their chosen paramour than your every day fan, but too often I found the movie fell back on lazy laughs at the expense of its subjects without exploring beyond the surface any of the themes that they raise. Saddest of all is Elif, the daughter of Turkish immigrants who is seen as a disappointment by her parents, who see their daughter has being corrupted by western ideas and now wants to be a musician like her idols of One Direction.

The film even gets its title from her as she screams hysterically over a video of her beloved One Direction, claiming this newfound devotion is so unlike her. Her story is a potent one of a young girl discovering a love for music through her obsession, but too often the videos of her – videos that went viral, no doubt to her embarrassment – continue to punctuate the film. Her hopes and dreams are real, but her reactions are a form of mania that audiences are all but asked to laugh at.

And it’s a subconscious thing a lot of the time, too. Pop music is just pre-packaged pap made for studio executives to make money off of the easily gullible backs of young audiences after the latest shiny pop bauble. Too many people are all too comfortable making jokes at the expense of somebody who prefers a drum machine to an acoustic guitar because pop music is objectively bad and you should know it. It’s an offensive and simplistic trap that I Used to be Normal falls into too often to ignore.

It wants to have its cake and eat it too, by letting you into the mind of fans while letting you laugh at them because you would never be so dumb as to be like them. Like the friend who’s eager to tell you they don’t like ABBA and yet sings along to “Dancing Queen” at every wedding they attend, I Used to be Normal can’t quite let go of its desire for cred with the cool kids – sadly, at the expense of its subjects.