Ford v Ferrari is a revved-up historic drama about friendship and frustration

A revved-up historic drama with top notch Christian Bale and Matt Damon performances proves to be an engaging and surprisingly nuanced study of finding satisfaction amidst life’s limits, writes critic Craig Mathieson.

Call it The Fast and the Curious. Director James Mangold’s ability to infuse unexpected detail and emotional relevance into familiar genres – an approach seen as early as 1997’s Cop Land and given stark fulfilment by 2017’s Logan – shines through in this automotive drama, where the goal of winning a supposedly unobtainable race becomes the lens for friendship, frustration and ultimately release.

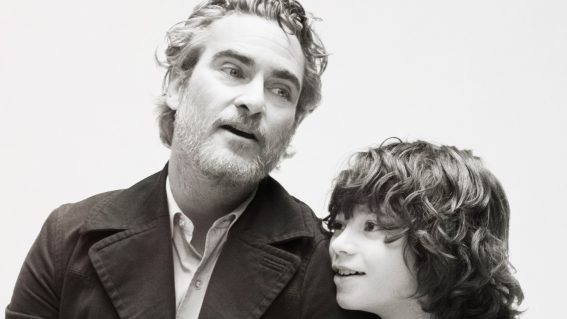

“You have to have a sense of where that limit is,” headstrong English race driver Ken Miles (Christian Bale) tells his son Peter (Noah Jupe), in one of several scenes that reflect on speed’s allure instead of merely celebrating it. Mangold has a similar and deeply satisfactory approach.

The set-up is conventional. In fact, a Hollywood studio could have made this film in the mid-1960s, when it’s set. A former champion driver trying to make his way as a designer and team boss, Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon) is tasked by a bastion of American capitalism, the Ford Motor Company and its autocratic boss Henry Ford II (Tracy Letts, terrific), with creating a car and racing team from scratch that can go to Europe and win the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans race in France. Shelby’s best driver is Miles, a World War II veteran who is opinionated, driven, and dismissive of interlopers. There are plenty of revs in that well-worn framework of feisty friendship and underdog appeal.

But at each turn Mangold illustrates deeper concerns with genuine empathy while never skimping on the engine whine and overtaking manoeuvres. You notice that for all his bark, Bale’s Ken is deeply connected to his capable wife, Mollie (Caitriona Balfe), who is more than a sounding board for his self-doubt, as well as Peter.

The qualities that scare Ford executives such as Shelby’s advocate, Lee Iacocca (John Bernthal), let alone oily saboteur Leo Beebe (Josh Lucas), don’t wall off Miles, who is more open to joy than rage. Both Bale and Damon give big performances, but they’re tied together by a back and forth that has a measure of insight.

Henry Ford II and Enzo Ferrari (Remo Girone) are both imperious oligarchs, making the plot more about individuals trying to navigate a fixed system than nationalistic fervour; Mangold shoots both men literally looking down on their workers as they address them. The process of testing and modifying a car is enjoyably crafted, with the character actor Ray McKinnon and his distinctive face prominent as Shelby’s down home engineer Phil Remington, while the race scenes use driving rigs and second unit legwork to get most of the racing shot in camera instead of being digitally composed.

The open face helmets means Mangold can hold on Bale’s face for comparatively long takes while driving, so that you can see emotions play over the angled lines. At one crucial point a bead of sweat sits just beneath Miles’ nose as he exerts himself. That’s the kind of granular detail that gives Ford v Ferrari a winning edge.