E is for The Evil Within: a horror movie disasterpiece, made over 15 tragic years

In monthly column The A-to-Z of Trash, bad movie lover Eliza Janssen takes us on an alphabetically-ordered trip through the best bits of the worst films ever. This month, the heartbreaking tale of The Evil Within; a twisted horror vision that just might be the actual Citizen Kane of bad movies.

It would be unfair of me to dismiss The Evil Within as trash cinema—even though the film does have its share of unintentionally hilarious, indescribable, and/or utterly tasteless moments.

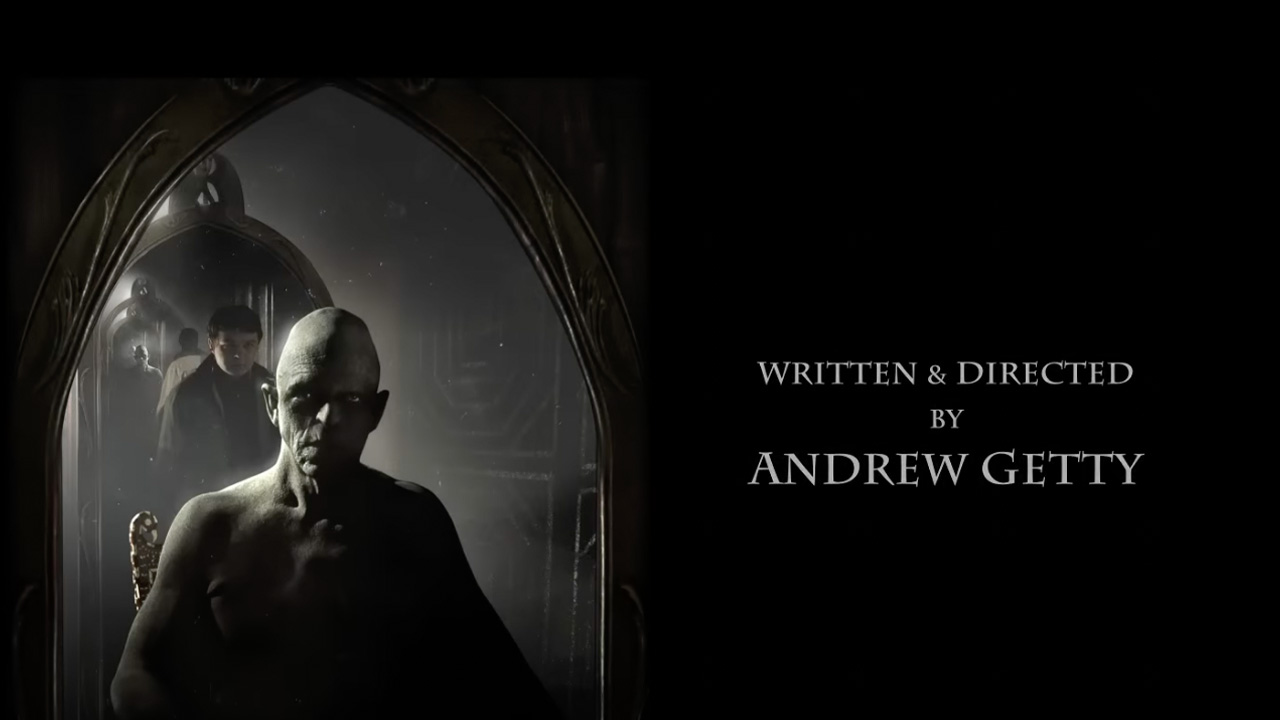

It’s probably the only movie I’ll cover for this column that has a bewildering 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes—and a 51% audience rating. The first and only film from Andrew Getty (yep, of the Getty Gettys) began filming in 2002 and was only completed in 2017, two years after the director’s tragic death in 2015.

A self-financed labour of love, Getty’s nightmarish vision was posthumously plonked into a few genre film fests and then onto YouTube and Tubi, where you can watch it right now for free. I beg of you: please, go ahead, watch the first five minutes of this misbegotten masterwork right now.

Keep in mind that these trippy, ingenious visuals came out the same year as David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return. A woman morphs into a doll, picked up by a child whose slow-motion eyeline leaves a black trail across a picture-frame: it’s super reminiscent of the shabby, arts-and-crafts-y, disturbing CGI in Lynch’s series, smoke and lightning and motion that earned that project international critical acclaim. Twin Peaks’ third season isn’t TV, many fans claimed: it’s one enormous, brilliant movie. The Evil Within isn’t a movie, I’d posit: it’s distilled trauma, an inherited lifetime of amphetamine-fuelled nightmares left to rot on Tubi. What could be more existentially horrifying?

Originally titled ‘The Storyteller’, Getty’s debut film is an angsty reflection on the tricks and illusions our minds exhibit to us—really solid material for a psychological horror movie. Unfortunately, Getty immediately hamstrings himself by casting the able-bodied TV procedural actor Frederick Koehler as a mentally disabled man. Like Forrest Gump, he loves ice-cream and has a childish crush on a more experienced, street-smart woman.

“You’re gonna have to get used to the way I speak out loud”, Koehler’s sneering narrator explains to us before we see him, stuttering and stooping like every archetypal disabled character any neurotypical performer has ever played: “my inner voice is considerably more sophisticated.”

It must be said that Koehler acts his bloody pants off in this difficult, often embarrassing double role, alternating between malevolence and whimpering naivety over the course of single sentences. Even just his generous scheduling commitment is impressive, considering that the actor would’ve had to step back into the uncomfortable role time and time again as Getty’s production was beset with funding issues and even lawsuits.

In sleep, Koehler’s hero Dennis is tormented by his own misanthropic doppelgänger, who can also take the form of The Hills Have Eyes horror legend Michael Berryman. In waking life, Dennis is patronisingly cared for by his brother Sean Patrick Flannery: he believes that his able-bodied sibling’s life would be “easier without a big dribbling mongoloid in it”, as one typically upsetting bit of dialogue reveals. The only way to bridge the two, torturous worlds is for Dennis to murder “kitties”, “doggies”, random neighbourhood kids, and anyone else who gets in his way.

In between that artistically bold, lyrical opening sequence and a bonkers, body-horror finale, The Evil Within is unfortunately bogged down by repetitive exchanges, many of which consist of Koehler screaming at himself as he regrets killing another innocent. Every so often, though, there’s a shot or unconvincing set that reminds us of this project’s mind-boggling hyper-specificity. Getty is clearly aiming to adapt his own nightmares as authentically as possible, pushing a camera through the plastic tunnels of a hamster enclosure or painstakingly engineering an animatronic, drum-playing octopus at a family pizza bistro. I love bad movies and I love good horror movies, and I’ve rarely seen a film that walks the line between heartbreaking failure and heart-stopping terror so precariously. Add in the fact that a far more widely-known horror video game was released in 2014 with this film’s exact title, and you’ll almost have me sobbing at the project’s misfortune.

Tommy Wiseau’s The Room is often touted as “the Citizen Kane of bad movies”, but I’d argue that this is an unsuitable comparison, suggesting only the popularity and cultural impact of both projects rather than any creative similarity. The Evil Within is much more like an aborted version of Welles’ movie, spiked with a lil of Inland Empire’s Hollywood horror sensibility. Both this flop and the 1941 classic were directorial debuts, of filmmakers who threw their whole selves into the medium and accidentally constructed self-loathing portraits of their own ego. The connection between the fortunes and corruption of the Hearst and Getty stories makes each project fascinating, forever tying each fictional tale to vaster American—and even particularly Californian—forces.

Welles, Wiseau, and Getty each project their hang-ups into self-aggrandising, attention-grabbing films, and so The Evil Within deserves to be newly appreciated as a feature-length cry for help from someone whose oil tycoon asshole of a grandpa perhaps cursed them from birth. Getty’s spoiled perspective has him comparing his inheritance to a disability, to the mental anguish of living in a warped CGI dream realm: it can be problematic and in poor taste, but it’s something you won’t find in any other work. It’s a true shame that we’ll never get a sophomore work from this iconoclastic, tragically lost nepo creative—or even just an interview in which he can explain what the fuck he was going for here.

In any case, it’s dope as hell that Andrew Getty got to use some of that family oil money to film a scene of a woman getting her brains expelled out of her skull via fire extinguisher. Vale.