The Girl Before is a sharp, edgy thriller – despite the melodrama and oversized wine glasses

A woman moves into an ultra modern house owned by a peculiar architect in this elegantly framed miniseries that remains compelling despite some drawbacks, writes Clarisse Loughrey.

These days, psychological thrillers are riddled with girls. There are girls on trains, girls that are gone and girls with dragon tattoos. These aren’t women, unless they are sitting by some alliterative window, but girls: girls with eyes as wide as the rim of their wine glasses, with frail limbs and fractured sanity.

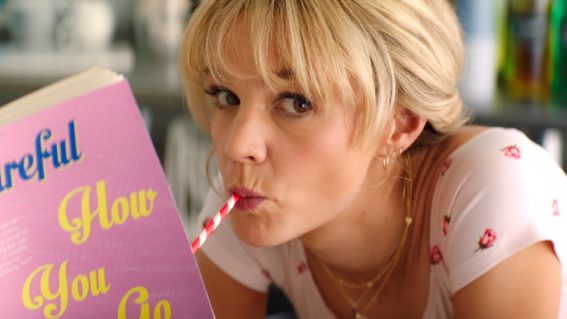

Now, we get The Girl Before—Emma (Jessica Plummer), to be precise—who is not averse to wearing oversized loungewear, as these girls often do. But who, most importantly, is dead. Another girl, Jane (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), now lives where Emma met her untimely end, having taken a tumble down the stairs.

Was it an accident? Was she pushed? Jane reflects quietly on the possibilities while pacing around her open-plan kitchen. Occasionally she catches a glimpse of Emma—in restless, phantom form—looking out forlornly from one of the house’s many reflective surfaces. The Girl Before, the first of JP Delaney’s easily consumable thrillers to be adapted to screen, may sound like precisely the kind of diverting nonsense that Netflix’s parody The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window recently targeted.

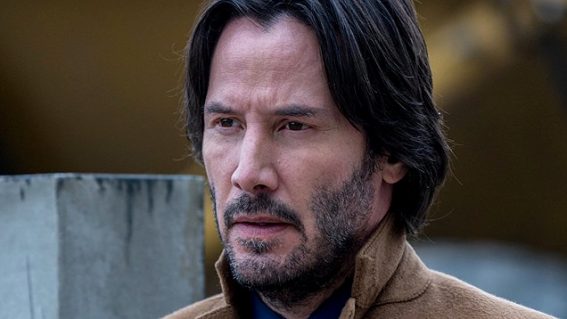

But there’s an edge here, as sharp as the blade on a steak knife, and an unexpected feel of austerity to the proceedings that’s baked into the very walls of the home these women (sorry, girls) move into. The place is a minimalist fortress, designed by a popular but authoritarian architect named Edward (David Oyelowo). The rental agreement includes a list of demands that rival those of the prince in Beauty and the Beast.

There’s no forbidden west wing here, but a requirement to banish all books, coasters, pictures, magazines. In fact, all the tenant’s belongings should be able to fit into a single wardrobe up in the bedroom space. And then comes the real red flag: why do Emma and Jane both look so alike? Is this a coincidence or part of a larger pattern? (It’s part of a larger pattern.)

The house, One Folgate Street, is so joyless in its construction—a Tetris set of concrete panels around a rock courtyard with a single, lonely tree—that the viewer might be tricked into thinking The Girl Before is a stealth Black Mirror spin-off. Series director Lisa Brühlmann, whose credits include Killing Eve and The Servant, has a clear sense of style and the camera has an elegant way of slipping room-from-room, character-to-character.

But though the house’s virtual control system, which functions a little like HAL 9000 for the IKEA generation, is unavoidably dystopian in its silent observation of the tenants, Delaney’s story is less about technology than it is about those who wield it. The extent of Edward’s controlling nature (dangerous or pitiable?) is, at times, indiscernible to us—largely because of how delicately Oyelowo approaches the role. He’s not as openly, manipulatively personable as a Patrick Bateman-type on the prowl. There’s a softness there that wants to coax out from us the words: “maybe he’s just misunderstood.”

The Girl Before, as a whodunit, lacks mystery due to the minuscule size of its cast. Its Hitchcockian touches are more repetitive than they are inventive. But there’s a compelling thesis behind Edward’s notion that “all buildings are designed to have an effect on people.”

One Folgate Street, then, offers the illusion of control. Over the course of the series, we come to learn why these women (sorry, girls) are so willing to give up so much of themselves for the promise of serenity. There’s a bedroom in Jane’s old place that she refuses to redecorate, a place where death lingers. Emma is not the same woman she once was, following a burglary where she was home and her boyfriend Simon (Ben Hardy) was not.

The show is smothered in a kind of upper-middle-class gloss, where everyone’s concerns are treated by officers and doctors with the utmost urgency. But it still manages to explore how women—especially women of colour—are regularly dehumanised by the systems supposedly built to protect them. And it’s a familiar story we’re able to explore from two very different perspectives, since Plummer and Mbatha-Raw’s performances sit at either end of the emotional spectrum.

Plummer is open, vulnerable, at times chaotic. Mbatha-Raw is restrained, but quietly imploding. The Girl Before, if you can put aside all the melodrama and the oversized wine glasses, is a convincing reminder that to rebuild ourselves, we must always start from within.