Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon is a telekinetic trip of style but not much substance

“Carrie on a frisky, strung-out weekend in New Orleans”: arty thriller Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon borrows some familiar supernatural tropes, says Eliza Janssen, and has juuust enough style and sick beats to get away with it.

The light of a full moon makes people stranger: who knows why? Maybe it’s just been baked into us through centuries of superstition, giving us some subliminal permission to let go of our inhibitions and romp in the darkness.

There’s no doubt that there is something truly supernatural going on in Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon, but it’s hard to say whether the titular telekinetic’s powers are tied to the big orb in the sky at all, as it goes from pure white to a portentous shade of red. We meet her in a psych ward, under the “care” of an abusive nurse when she quickly snaps out of catatonia and bites back. Is the moon to blame, or has Mona Lisa (Jeon Jong-Seo) awoken purely because we, the audience, are watching her?

Director Ana Lily Amirpour introduced herself to the international arthouse with the impossibly cool Iranian vampire flick A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, then dipped in critical esteem just a bit with The Bad Batch, another story of an embattled loner in a sick genre setting. Her third feature takes itself a bit less seriously than those hip horror films, but it also relies on some tropes and character dynamics you’ve certainly seen before—resulting in something less original than Amirpour’s other works.

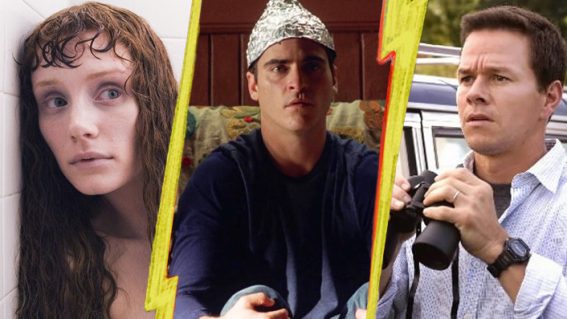

There’s the Good Cop (Craig Robinson) haunted by his mind-controlled encounter with Mona Lisa; the lonely emo kid (Evan Whitten) with whom she falls into a Boy And His Monster relationship; and the sex worker with a heart of gold (Kate Hudson) who takes Mona Lisa under her wing. She for one blames all the oncoming violence and mayhem on the current lunar cycle. “I knew something freaky was gonna happen tonight”, Hudson’s pole dancer purrs after seeing proof of Mona Lisa’s unexplained abilities: “with the full moon, I like, feel it in my ovaries.”

Me? I think Mona Lisa’s power, and the film’s most succulent themes, are derived from the fact that she’s barely a character at all. With no memory of her real name or where she came from, she wanders from the asylum through a bayou and into New Orleans’ most noisy, touristy quarter. Everyone she encounters immediately measures her up for what they can inflict upon her: greasy frat bros want to hit on her, the cops want to cuff her, and Hudson, herself a woman bitterly profiting off the male gaze, sees the super-powered stranger as a moneymaking venture. Jong-seo plays the protagonist as a mirror, darkly projecting the unkindness of strangers back into their faces whilst not seeming to want anything for herself but survival.

Spongelike, she’s able to hover from one situation to the next without really developing a sense of autonomy, which is effectively sad but not especially energising in terms of story. She seems to appreciate humanity’s decency through Hudson’s son, a fellow neglected child and kindred soul, and a tatted-up sleaze played by Ed Skrein returns in the film’s third act as a surprisingly sweet and supportive character.

But through Amirpour’s aloof, edgy style, Mona Lisa is always a cipher, and her initial insights on the human race aren’t elaborated upon beyond her first, bloody encounter with Robinson’s terrified cop. Before manipulating him to shoot himself in the leg, she asks him icily, “do you like people? Why?” The movie almost delves into misanthropy itself with a later scene of violence against Hudson, which feels like distasteful and disproportionate comeuppance.

The soundtrack, full of sweaty, thumping alt-dance beats is a real highlight. Italian composers Daniele Luppi and Bottin keep that nocturnal, N’awleans vibe centred, making the threatening scenes a little lighter and the slower, daytime sequences blip by like necessary breathing space. Were it not for Amirpour’s good taste and laid-back visual style, the film’s straightforward (anti-climactic, even) ending could’ve made this whole project an overfamiliar missed opportunity—Carrie, but on a frisky strung-out weekend in the South.

Under the moonlight, though, it all looks and sounds like an exhilarating, trendy trip. As long as that’s what you’re looking for in Amirpour’s shadowy reflection of a main character.