The meaning of Fantasia, Disney’s beloved psychedelic masterpiece

This year marks the 80th birthday of Fantasia, Disney’s phantasmagoric animated masterpiece. To mark the occasion, critic Luke Buckmaster does the unthinkable—and explains what this trippy classic is really about.

If attempting to determine the reason, the point, the very raison d’être of Fantasia strikes you as like throwing mud at a wall and trying to make it stick using a hammer and nails—well, fair enough. Disney’s beloved 1940 classic, which turns 80 this year, occupies a legendary place in cinema history as the pièce de résistance of Big Mouse psychedelia: the closest Walt and co. ever got to visualising the effects of LSD.

See also

* Best new movies and TV series on Disney+

* All new streaming movies & series

But as I rewatched the film in honour of its 80th birthday—and also because it’d been quite a while since I’d seen it, or consumed enough consciousness-expanding drugs to replicate its kaleidoscopic qualities—a strange and perhaps hubristic thought dawned on me. I reckon I’ve finally figured out. The meaning of this surreal, magnificent dreamscape.

Fantasia is most famous for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, an illustrated segment scored to the titular track (from French composer Paul Dukas) which is the easiest to follow, narratively speaking, of the film’s eight dialogue-free segments. It stars Mickey Mouse, who, garbed in plush red robe and pointy blue wizard hat, summons a straw mop to life to do his bucket-carrying work for him—an innovative initiative that ultimately leads to disaster, when the formerly inanimate object multiplies like Mr Meeseeks.

This cautionary tale about not avoiding real work incorporates a literal kind of magic, involving sorcery and all. The broader production is magical in a more general sense—with its electric otherworldly visions, from dancing hippopotami to ice skating fairies and towering demons the size of cities.

Music is inseparable from these swirls of colour and light. The Philadelphia Orchestra performed seven of the eight recitals featured in Fantasia, which include the Nutcracker suite (Tchaikovsky), Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (Bach) and Rite of Spring (Stravinsky).

In between these segments, an MC—music critic and composer Deems Taylor—addresses the audience. In his first appearance he thanks the film’s key creative talent and describes the production as nothing less than “a new form of entertainment.” As much as I might claim to have “figured out” the point of Fantasia (and yes: I’m getting to it) it is Taylor himself who comes very close to directly explaining the riddle of the film.

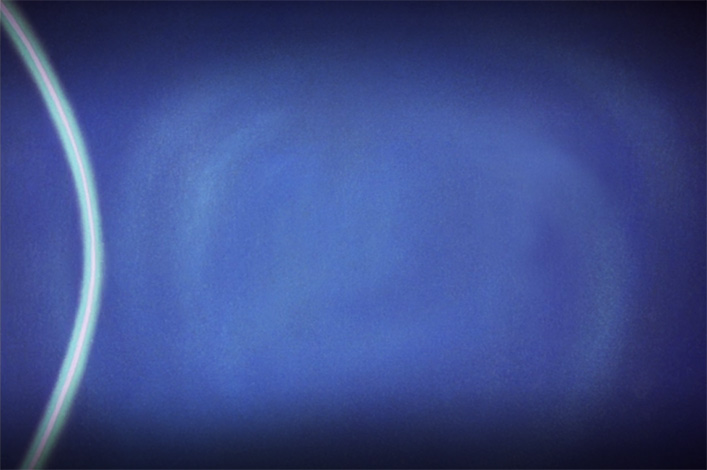

The crucial illuminating moment arrives just after the intermission, when the MC returns to introduce a special guest. It is not a question of who this guest is but what. Because the special guest is—wait for it—the soundtrack. “It’s alright, don’t be timid,” beckons Taylor, before the film cuts to a blueish background in front of which a curved white line appears, looking like a sort of electric rope, ensconced in pulsating blue light. This is the soundtrack.

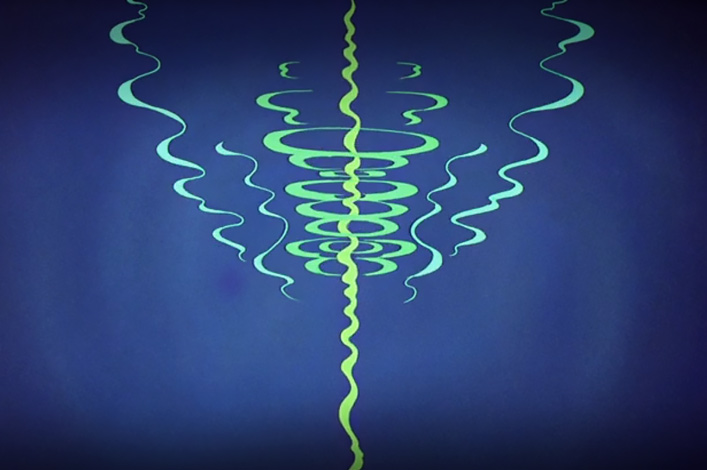

Loosening his guest up with a bit of flattery (“every beautiful sound creates an equally beautiful picture”) Taylor then requests from the soundtrack a series of noises, as if it were a cover band at a pub. When he asks for a harp, the soundtrack obliges and transforms into swirls of squiggly yellow that turn green and multiply, cascading beautifully down the frame, creating ripples that create ripples.

A range of other instruments (including a violin, flute, trumpet and bass drum) are requested, leading the chameleonic soundtrack to conjure different illustrations, attempting to explain in visual terms the presence and impact of a sound.

And that, friends, is the very reason, the point, the raison d’être of Fantasia. The nail that hangs the mud to the wall. This film is about visualising music. It might sound simple but it involves an infinite array of creative possibilities. This deeply imaginative process goes to the heart of what makes the film special.

Music videos to some extent embrace the challenge of visualising music also, most commonly applying the model used in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice—a cohesive visual narrative accompanying a soundtrack. In such instances the story can be understood even if the music is muted, the sound and images evoking separable experiences. Fantasia does more than that, crafting not only broad visual accompaniments but note-by-note illustrations.

That ‘here’s old mate soundtrack’ exchange underscores how central the challenge of visualising music is and how seriously the film regards this process—while also embracing it in a jocular and playful style. The argument that the orchestra weren’t just hired help but are in fact authors of the experience spilled over into real-life when The Philadelphia Orchestra Association sued the Big Mouse over profits in the 1990s, essentially arguing they were the film’s co-creators. The dispute was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.

As it dances around with its striking colours and sounds, the film does more than create a cinematic LSD equivalent: it asks us to think differently about the nature of art and authorship. Take for example the way Taylor introduces the hugely ambitious The Rite of Spring segment, a Darwinistic illustration of the first few billion years of earth’s existence, from the Big Bang to dinosaurs and beyond. He says “science, not art, wrote the scenario of this picture.”

That is quite something to hear in a family film, or, in fact, any film; a line like that stays with you. Earlier in the piece, the MC explains that each segment follows one of three different approaches. They are “the kind that tells a definite story,” the kind that “has no specific plot” but paints “a series of more or less definite pictures,” and the kind with “music that exists simply for its own sake.”

The first has narrative clarity, the second contrived elegance, the third abstract beauty. None are ‘better’ or more worthy than the others. Great art, as Fantasia reminds us, is not about easy definitions or playing by the rules.