Retrospective: Hitchcock’s only B-movie The Birds turns 60 years old

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 horror film The Birds celebrates a big anniversary, and Eliza Janssen finds plenty of material for its sinister, sexually-charged secret reading upon rewatch.

“WHY DID THE EAGLES AND VULTURES ATTACKED?” So goes the tagline for the infamously crap 2010 film Birdemic: Shock and Terror, a bad-movie-night classic directly inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, made almost 50 years earlier.

It’s a very valid, if grammatically incorrect, question. In The Birds, all the film’s townsfolk shaken up by the arrival of Tippi Hedren’s protagonist are asking it constantly: why would an entire bay’s bird population suddenly become bloodthirsty? Is it because of her?

Rewatching The Birds on its 60th anniversary, I feel more certain than ever that this is the solution—that Hedren’s Melanie Daniels is the sexually-charged catalyst for all that doomsday pecking and squawking. I also realise now that The Birds isn’t as distant from Birdemic as it might seem, despite the yawning abyss of difference in their impact and filmmaking quality. They’re both B-movies, and The Birds may be the only B-movie Hitch ever filmed.

In Hitchcock’s filmography, it comes out a year after Psycho, another horror film about fatal mommy issues, and about 10 years before Frenzy, another solid contender for the director’s grimiest, nastiest movie. But in my opinion, The Birds stands out for its genre trappings as a creature feature, and its refreshing tackiness amongst Hitchcock’s more sophisticated stories of deals and duplicity and adult romance.

There are unconvincing seagull puppets, exposition delivered through radio newscasts with very convenient timing, and a wonderful third-act sequence of townsfolk arguing in Bodega Bay’s diner, spouting off their opinions about the ongoing carnage like the supporting characters in any Roland Emmerich film do. There’s no eloquent murderer here, forcing our main characters to outwit them before they strike again in lush black-and-white. Only feathery darts of death, spilling jammy red blood down the faces of some not particularly talented kid actors.

The bird effects were created at Walt Disney Studios with an archaic greenscreen-esque technique known as “sodium vapour process” or “yellow screen”, filling frames of Hedren and the town with hundreds of superimposed fowls. This is still a Hitchcock movie, so when sparrows flood down the Brenner household’s chimney and flutter madly in the family’s faces, we buy their questionable FX thanks to his buildup of suspense just before the flurrying begins. But where’s the music, in between the clattering of wings and the long, heart-pounding silences that plague the film?

In strong contrast to Bernard Herrman’s seminal, lush work on Psycho the year before, he’s credited here as only “sound consultant”—because The Birds has no non-diegetic music at all. It’s an eerie and brilliantly modern choice, highlighted best in the horrifying midpoint scare where Lydia (Jessica Tandy) doesn’t even scream when she finds a farmer dead with his eyes pecked out. It’s one of the most stark and stylistically experimental ways in which The Birds strays from its ‘man vs. nature’, B-movie quality.

The other major exception is the movie’s wild, somewhat troubling themes of obsessive female sexuality. Don’t believe me? It’s right there in the title, with “birds” being a common synonym (and a diminutive one at that) for women in Hitch’s native England. From her opening meet-cute with hunk Mitch (Rod Taylor), Melanie is instantly the kind of character who’d be considered problematic AF if this were a 2000s-era romcom, and if she were the male protagonist instead of a mischievous, spoiled socialite. Just to flirt with him, she pretends to work in the pet shop he enters: he’s looking for love birds as a gift for his sister Cathy. “As she’s only turning 11, I wouldn’t want a pair of birds who were too…demonstrative”, he implies. “At the same time, I wouldn’t want them to be too aloof either”.

Okay sir, so you want birds that can fuck but aren’t too reproachably horny. Got it. Hollywood’s Hays Code would only be abolished five years after The Birds’ release, meaning overt references to sex were still encouraged to be coded as wondrously as Hitchcock did in the infamous three-second-kiss scene in Notorious. But by the time Melanie has bought the birds and driven hours to Mitch’s seaside small town to deliver them, we can sense what’s being censored here. She’s the prototypical Hitchcock blonde—glamorous, icy and driven—and because she’s a woman behaving badly, only bad things can follow.

Mitch is the only significant male character in The Birds, and he’s really very boring, necessarily stepping into a tired action-man role in the film’s finale. All the women encircling him in Bodega Bay are more interesting. Their lives are defined by his presence, each representing some twisted facet of womanhood. The Birds is loosely based on a novella by Daphne Du Maurier (also responsible for the novel Rebecca, another Hitch-adapted tale of female jealousy and repression), but it’s scripted by a guy and directed by a guy, resulting in a mysterious and powerful story that secretly skirts the territories of both feminism and outright misogyny.

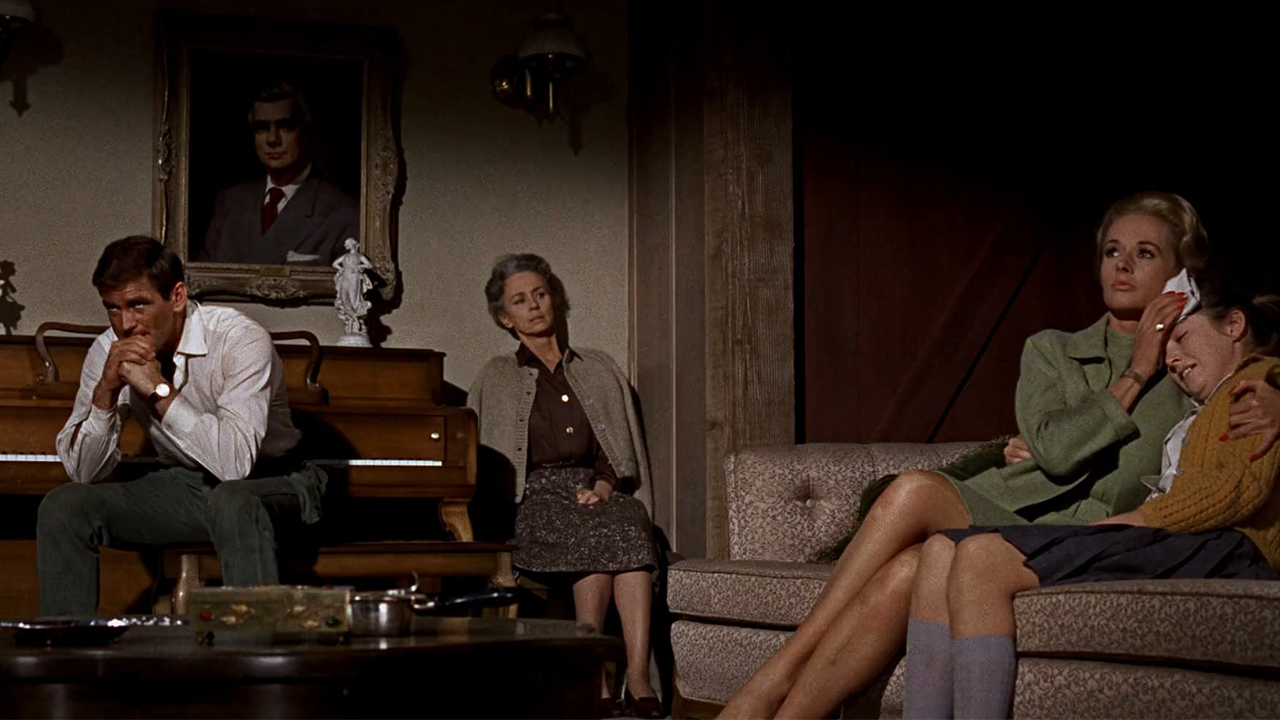

Mitch’s little sister Cathy (Veronica Cartwright) is purity and innocence personified: his spurned ex Annie (Suzanne Pleshette) is like a slightly more butch, earthy version of Melanie, with a deeper voice and brunette hair. Wife Material, Mark 1. But the greatest mirror to Melanie’s selfish, desire-driven party girl is Mitch’s controlling mother, Lydia (Jessica Tandy). The women have practically the exact same hairstyle! And Mitch has fallen into the role of surrogate husband to her after his father’s death, calling her “dear” and “darling”: cattily she warns him of tabloid gossip surrounding Melanie, trailing off on “but when you bring a girl like that home…”

The scenes of crows, sparrows and gulls descending into chirpy violence always escalate when there’s conflict, in dialogue or just a sour look, between any of these obsessive women. And when she sees the Oedipal hold Lydia has on Mitch, Melanie swoops in to take a frightened Cathy under her wing (jeez sorry, two bird puns in one sentence), which of course only makes the havoc intensify. Men are depicted as trophies or protectors, proven when Melanie updates her rich father over the phone and all the surrounding male characters look her up and down: “No, I’m not being hysterical”, she coos down the line. “…Alright daddy. Yes, daddy.”

This rewatch was my first time noticing a pivotal bit of Melanie’s backstory: she reveals to Mitch that her mother “ditched her when she was 11”. The same birthday Cathy’s celebrating, amidst all the flying terror that arrived in town the same day Melanie and her lovebird gift did. So did she cause the whole thing? Yeah, I think so: the flurry stops after she’s attacked in the attic by owls and gulls, bleating “get Cathy and Lydia out of here” in a moment of redemption. The trauma humbles her ambition, a changes that’s additionally disturbing and morally questionable due to Hitchcock’s very real terrorising of Hedren on set, replacing the mechanical birds in the scene with real ones without her knowledge or consent.

After the birds have abused Melanie into catatonic civility, both she and they are docile: watching the family drive out of the darkened, apocalyptic-looking small town with beady eyes that seem to say “that’ll learn ya”. No longer a spoiled, spirited rich girl, she cowers into Lydia’s chest, having now suffered enough to be accepted into this broken domestic unit. To be accepted as a Good Woman. If bird puppets don’t haunt you, this Blanche DuBois-esque character turn certainly will.

Upon release, The Birds was savaged in some reviews for the same reasons I’m praising it now: “the worst thriller of Hitchcock’s that I can remember”, “shock for shock’s sake”, “a sorry failure…sadism all too nakedly present.” I wonder if these same critics enjoyed the dull ending of Psycho, in which a psychiatrist drudgingly explains why the villain we’ve loved and then feared for 90 minutes is such a nutcase.

I say The Birds is a terrifically fun and scary creature feature, with a truly unsettling mystery at its core that hints at the dangers of repressed female sexuality at best—and outright incestuous paranoia at worst. Both the surface level of flappy mayhem and its dark underbelly work, all these years later: follow it up with a viewing of Birdemic to appreciate its terror even more.