Natasha Lyonne is great in Poker Face, but Columbo remains the greatest TV detective

Seen That? Watch This is a weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, Poker Face inspires him to revisit Columbo.

The reverse whodunit or “howdunit” format is enjoying a mini renaissance, thanks to Rian Johnson’s new series Poker Face—starring Natasha Lyonne as a bullheaded, jive-talkin’ quasi detective. I say “quasi” to distinguish her character, Charlie Cale, from payrolled sleuths working for the fuzz or private detective agencies. Traipsing across America, on the run from a casino magnate who wants her dead, Charlie squeezes in time to solve the latest murder, most involving people she’s recently met. By the time the body’s cold, the protagonist needs to be somewhere else—lest she joins the growing collection of corpses.

What distinguishes Charlie from other investigators is a superhero-like special ability to tell when somebody’s lying. This, along with her rogue status and brassy, bird-flipping flipping personality, gives the show a marketable point of difference from standard murder mysteries. Nevertheless, Lyonne’s character—and the show more broadly—lives in the shadow of the greatest television detective of them all. His name is Lieutenant Columbo.

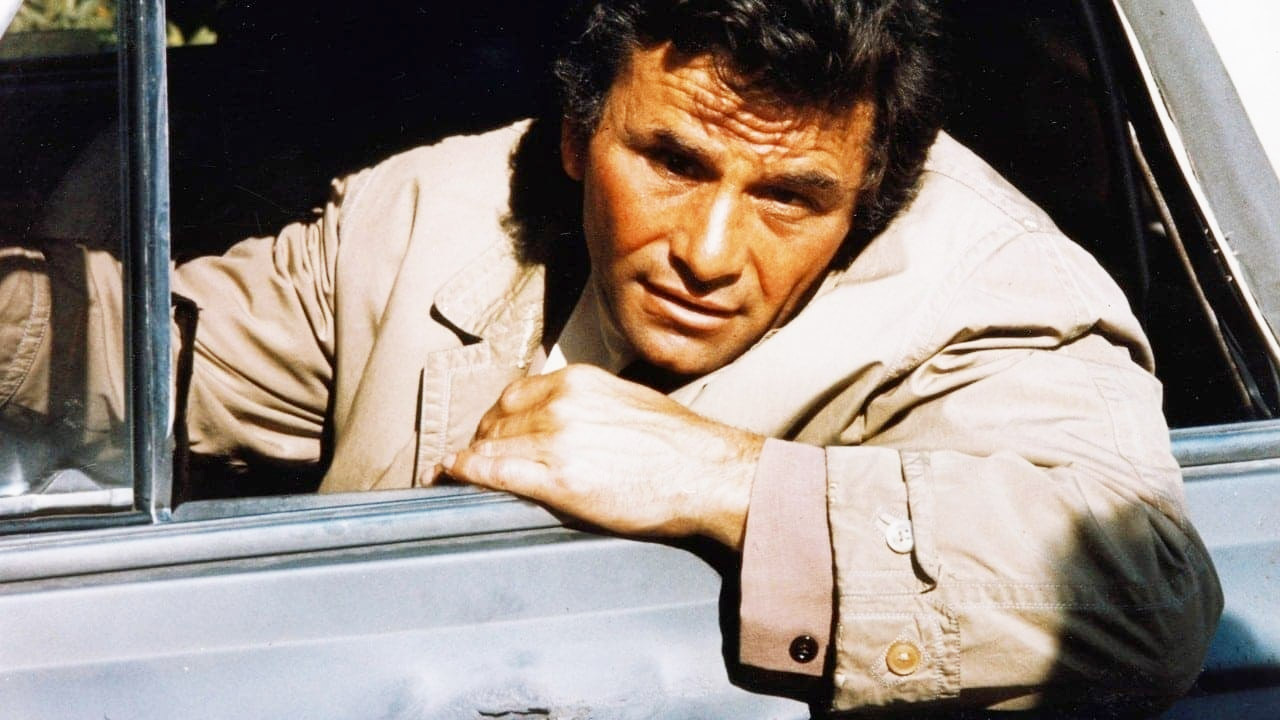

The words “Peter Falk as…Columbo” adorn the beginning of every episode of the massively successful series, which commenced in 1968 and ran for 10 seasons (plus various specials) until 2003, with various gaps along the way including a 12-year break between season seven and eight. That title card triggers a dopamine hit for fans, preempting the arrival of a thoroughly original character played by a brilliantly charming and low-key Falk, carving out a space that truly merits that overused descriptor: “inimitable.” Scruffy, personable and disarming, with a signature quint (due to Flk having one glass eye) and slightly aloof swagger, as if he’s always partly somewhere else, Columbo’s brilliance involves getting right in the face of the culprits—while conversing with them as if they’re old chums.

One lesson from the gospel of Columbo: sometimes the smartest thing to do is to conceal one’s intelligence. This comes in part from his unkempt appearance, famously dressed in a crumpled beige overcoat and looking—as one woman amusingly describes him in the third episode of the first season—”like an unmade bed.” Nor does he sound like an authority: instead of flexing his power and grilling suspects, Columbo presents himself as a person fussing about in details, making comments such as “I just get bugged by those little things” and beginning sentences with his famous “just one more thing” catchphrase.

The murderers Columbo investigates are typically clever, well educated, cultured people who initially assume he’s a bit of an airhead. By the time they realise the truth about him it’s too late for them. Some characters cotton on to his unprepossessing shtick faster than others, but rarely do the show’s writers directly address it. One exception is the following exchange, from 1971’s Ransom for a Dead Man, during which one villain absolutely nails his style.

Leslie Williams: You know, Columbo, you’re almost likeable in a shabby sort of way. Maybe it’s the way you come slouching in here with your shopworn bag of tricks.

Lt. Columbo: Me? Tricks?

Leslie Williams: The humility, the seeming absent-mindedness, the homey anecdotes about the family, the wife, you know?

Lt. Columbo: Really?

Leslie Williams: Yeah, Lieutenant Columbo, fumbling and stumbling along. But it’s always the jugular that he’s after. And I imagine that, more often than not, he’s successful.

In the reverse whodunit or “howdunit” format, the killer’s identity is never a mystery. Each episode of Columbo begins, like Poker Face, by showing the murderer execute a nefarious and usually very clever plan, before the shabbily dressed detective ambles along and blows it apart. This format, which obviously doesn’t include the guessing game involved with most murder mysteries, means the writers don’t get tempted by silly surprise twists engineered to out-manoeuvre the audience.

But it’s not quite right to say there’s no mystery. The big question mark hangs over how Columbo will crack the case; what evidence he’ll use to provide incontrovertible proof of their guilt.

Episodes (at least in the first two seasons, which I rewatched for this article) are generally directed in an unflashy style emphasizing details and Falk’s irresistible performance. But every once in a while a stylistic flourish takes you by surprise. For instance the first episode of season one, directed by Steven Spielberg, begins with the sounds of a typewriter in lieu of a score, the noise of the keys having a hollowed out, lingering effect. Better yet: the second episode has one of the coolest uses of split screens I can recall from any TV series. After the killer has done the deed, we see, in each lens of his glasses, a visualization of his plan for cleaning up and concealing the body. Here’s a still shot.

Perhaps the reason aesthetic chutzpah is so sparingly used is because everybody understood the main attraction—Falk, of course—was far better than any embellishment or special effect. It’s a performance of wonderful contradictions. Columbo can fill the room and fade into the background. He’s piercingly bold but laidback. He’s your best friend; he’s your worst enemy. He’s smart but looks like an idiot. He’s unerringly modest, but remains the greatest screen detective of them all.