Monsters Inc. is the Pixar franchise you never knew was a metaphor about climate change

While watching the new Monsters Inc. spin-off series Monsters at Work, critic Luke Buckmaster suddenly realised what this franchise is really about.

I always dug the premise of Monsters Inc.: cute toy-looking creatures scare the shit out of little kids in order to harvest their fear, which powers an alternate world with even more deranged energy extraction processes than our own. I liked the franchise even more when, watching the enjoyable first two episodes of its new spin-off series Monsters at Work, it struck me that the narrative is actually a clever metaphor for weaning off fossil fuels and embracing a future in renewable energy.

See also:

* Movies now playing in cinemas

* All new streaming movies & series

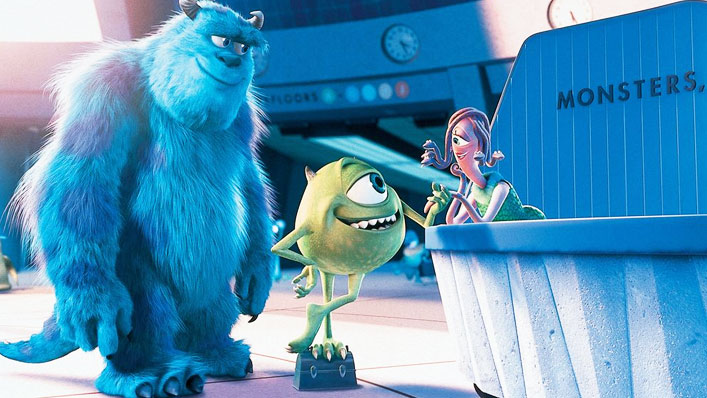

If that sounds like an ambitious reading, au contraire: it’s so obvious I almost felt ashamed for not noticing it earlier. A scene near the beginning of the first film practically illuminates this message in flood lights. Mike (voice of Billy Crystal) and Sully (John Goodman) watch a new commercial for their mining company-like employer, replete with images of hardhat-wearing staff and a voice-over explaining that Monsters Inc. extracts energy used to power every light bulb, every vehicle, every appliance in the city.

The commercial also acknowledges that change is afoot and the energy industry isn’t what it used to be (because “human kids are harder to scare”). The barons who have long raked it in using old extraction techniques—such as the bowtie and vest wearing Mr. Waternoose (James Coburn)—must adapt to a changing world or risk consigning themselves to oblivion. At one point Waternoose describes the situation as an “energy crisis” and is on the lookout for alternative power sources.

Part of this search involves—like dubious carbon capture technology being developed in the real world—looking in the wrong places. Enter the slithery purple chameleon Randall Boggs (Steve Buscemi), who has been developing a “scream extractor” he spuriously claims will revolutionize the industry. Like carbon capture technology it offers, at best, a stopgap solution that doesn’t address the core of the problem: that energy production and distribution must change.

By the end of the film, a new renewable energy source has been discovered: laughter. It’s clean, cost effective, and, like solar and wind, doesn’t have hugely detrimental long-term effects. Transitioning to this energy source is a no-brainer, but political conservatives—in the world of Monsters Inc. and in our own—are uncomfortable with the concept of change. The film shows, however, that the same companies who created the energy crisis can be part of the solution.

Like the coal mining industry, the scare industry in Monsters Inc. contains many essentially decent people (well, monsters, but don’t hold that against them) who just want to earn a crust—and perhaps take some pride in their work. They’ve been conditioned to believe there’s nothing wrong with a deadly and dying industry, whose failures are not their fault—though the smarter among them understand the need to rethink what they do.

The first episode of Monsters Inc. culminates with the protagonist, Tylor Tuskmon (Ben Feldman), ruefully crossing out the word “scarer” on his job description and writing above it “jokester.” He’s sad because he always had a vision in his head of what he would be doing professionally with his life—and the vision no longer fits reality. Still, he recognises the need to adapt; the company, and the city of Monstropolis, are transitioning to laughter as a viable energy source.

This conversion requires monsters to perform comedy routines in order to, as Donald O’Connor from Singin’ in the Rain put it, make ‘em laugh, removing the delicious wickedness of the premise. Which is sort of sad. But the franchise retains its ability to satirize the process of energy extraction. These are for instance the first words spoken in Monsters Inc., from an assessor behind a control panel who manages training simulations and also appears at the beginning of the first film:

“Take your position, on the mark, in front of the closet door, then proceed to perform your humorous dissertation or series of physical buffooneries for the artificial child. The metrics of your performance will be measured by our humour gauge, as well as our power gauge, which indicates the amount of giggle watt energy produced.”

The derivative 2013 sequel Monsters University is one of those follow-ups devoted to answering questions nobody asked—in this instance involving what Mike and Sullivan were like during their tertiary years. It’s limited in every way, including as a fleshing out of the clean energy / fossil fuel metaphor. It does make a point however about how energy companies ingratiate themselves within our social and cultural fabric, running initiatives designed to appeal intergenerationally in order to ‘get ‘em when they’re young.’

In the real world these initiatives are many and varied, including a children’s mascot named Hector the Lump of Coal (seriously) and propaganda materials distributed to classrooms. In Monsters University, uni clubs recruit youngsters and gameify elements of what will become the mining-esque experience—with freshmen for instance chosen to participate in the ‘Scare Games’. Little do they know, the profession they are preparing themselves for will one day—sooner than they think—cease to exist.

That’s life, eh? Change is coming whether we, or our politicians, or magnates such as Waternoose or Rinehart or Twiggy or Adani, like it or not. Sometimes change is positive and happens fast. In reality, for example, renewable energy sources are now cheaper to build than coal is to operate. In the universe of Monsters Inc., making children laugh powers cars, computers, toasters. An energy source built on hilarity? Sounds pretty good. But for the time being, in the real world, we should probably stay focused on wind and solar.