Host is a lean and loud in iso horror movie filmed on Zoom

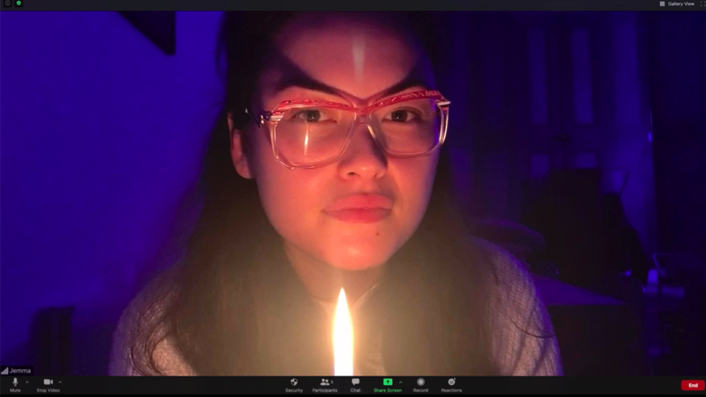

Now streaming on Shudder, Host follows a group of friends who conduct a séance over Zoom. It’s a nervy-jangling fright fest that resonates with the current moment, writes Luke Buckmaster.

First, a prediction: the ‘screen thriller’ genre will never really take off, and never entirely go away. Not for as long as we have screens in our lives. Films such as Searching, Unfriended and now director Rob Savage’s in iso horror movie Host—about a group of bored friends who participate in a séance over Zoom—have more than a little curiosity value, combining the grammar of film language with the design and processes of day-to-day computer usage.

Read more

* Here are the best titles to watch on Shudder

* All new streaming movies & series

This combination creates interesting offshoots that have a basis in both but are the exclusive domain of neither. Zoom users for example will likely discover many of the cuts in Host are so seamless they’ll barely even notice them, because they are informed by learned processes. Some of these cuts simulate the app’s ‘speaker’ mode, which switches to whoever is talking and presents them in full screen.

Savage and editor Brenna Rangott aren’t bound by this; they cut when they want. But the question beckons: who is in control of the speaker mode process? In one sense it’s governed by the user (because they know if they speak they’ll be enlarged) but the computer ultimately determines the outcome. This is compelling in the context of a scary movie, because horror films are about struggling for control or losing it completely. What if an angry spirit and a computer teamed up: the ghost in the machine, as it were, working with a ghost in real-life, breaking the rules of both physical and virtual worlds?

That is one of the more intriguing things about Host, though one senses it might have been explored accidentally—given this isn’t an experience for which the word “cerebral” immediately comes to mind. The story follows a familiar trajectory: cheerful reckless youngsters engage in mischief before something ghoulishly terrible emerges to wipe the smirk off their faces. Haley (Haley Bishop) sets up the Zoom call, bringing together six friends who don’t treat the exercise seriously, having a laugh and warming up for the occult world by slamming shots.

An older Irish woman (Seylan Baxter) joins them to facilitate the spirit-whispering side of things, though “whispering” doesn’t quite reflect what’s in store—i.e. screaming, shrieking, door slamming and various instances of ‘what’s that behind you?’ Before the carnage arrives, the characters play around with Snapchat-esque filters and one puts up a virtual background, which adds another layer of unreality, another kind of apparition.

Clocking in at a slight 56 minutes, this lean, compact chiller is directed with discipline and doesn’t overstay its welcome. While the narrative never feels remotely original, its aesthetic evokes a sense of immediacy for obvious reasons—with so many of us on Zoom these days—and its messages about isolation and virtual presence also resonate with the present moment. Now is a time when many of us are grappling with communal solitude; what it feels like to be lonely together. I write this from the perspective of somebody living in Victoria, a state that, at the time of writing, is in strict lockdown due to a second wave of the coronavirus.

It would be a bit rich to describe Host as a metaphor for the fear of isolation, or a metaphor for anything, given how happy Savage is to crank the dial and send the film into nerve-jangling cliché convulsions. But it does reflect contemporary forms of powerlessness. Not just iso-related but fears pertaining to a world of digital encroachments in which most of us recognise, to various extents and in various ways, that we can no longer fully trust our eyes and ears. It’s a shame Savage didn’t do more with the idea that the evil spirit is twisting the virtual environment; for a much better film that delves into that, check out the 2018 thriller Cam—a terrific example of truly contemporary aesthetic exploring truly contemporary conditions.

The performances in Host are universally effective in their snotty coarseness and fingernail-chewing intensity (I’d be interested to hear actors discuss whether performing in front of a webcam is easier or more difficult—I suspect the former—than a standard movie camera). Host is lean and loud but also limiting—as a film and as a format. I’d like to see a version with the viewer able to toggle between screens themselves, maximising, closing and shifting windows as we do on our computers. That feels like a natural extension of the experience.

Unlike the found footage film, which is predicated on the idea of witnessing an unalterable record of the past, the screen thriller alludes to the present and implies real-time elements. Real-time content is the fundamental form of computer-based art, requiring a reciprocal relationship between user and machine. There is a place for hermetically sealed forms of art such as movies, of course. But in a film about real-time computing, that uses an app as both its central location and its primary means of representing reality, it is hard not to leave the experience wanting to dive in. Into the virtual interface, that is: the characters can have the séance and the shrieking and the evil spirit to themselves.