Why the Shaun the Sheep Movie is a modern masterpiece

With the sequel to the Shaun the Sheep Movie on the horizon, Luke Buckmaster revisits the original film – and explains why it is one of the finest cinematic achievements so far this century.

The trailer for Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon recently arrived and, sheesh, it doesn’t look pretty. Or perhaps a better way of putting it is that the surface of the film looks impressive – maintaining the gorgeous stop-motion aesthetic we expect from Aardman Animations – but other elements show cause for concern. The introduction of a cute cuddly alien character for instance, as if squeezed in at the request of the merchandise department. And also the presence of a slappable-sounding American voice-over man making bad jokes, such as “one small step for lamb, one giant leap for lamb-kind!”

Why do I care? Because its predecessor, 2015’s Shaun the Sheep Movie (a feature-length spin-off of the Shaun the Sheep TV series) is a brilliant movie – so the sequel has huge, hoof-shaped shoes to fill. I am far from the first critic to heap praise on co-directors Mark Burton and Richard Starzak (who have not returned to direct Farmageddon) for constructing such a delightful work of art: so spirited, lively, inventive, humane. Yet I can’t help but feel that this magnificent production – packed full of jokes and frequently laugh out loud funny – doesn’t get the kudos it deserves, perhaps due to its kiddish marketing materials and young core audience.

Shaun the Sheep Movie is dialogue-free, a decision that makes it a bolder work than Aardman’s other fine films including (and especially) 2005’s Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. This decision also means it is not just a silent film but a film that in a sense is more silent than the vast majority of productions made during the early years of cinema. These films had no audio but most had dialogue, with intertitles displaying the characters’ speech. The films that didn’t use intertitles stood out – such as F.W. Murnau’s great 1924 drama The Last Laugh, which relies on expressionistic camerawork and pantomime to tell a sad story about an ageing hotel doorman.

In the Shaun the Sheep Movie, no dialogue and no intertitles means everything – from the smallest gag to the largest plot point – needed to be written and depicted visually. No slabs of exposition, no announcing or repeating details through dialogue. In the great craft they demonstrate, which is necessary to tell cinematic stories pictorially, the directors remind us that the fundamental aspects of film and television are movement and images – the essential elements of “motion pictures.”

Burton and Starzak embrace the properties of great silent comedy – the cinema of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton – from a modern point of view, crafting an experience obviously old in some ways and obviously contemporary in others. When the characters leave the familiar surrounds of the Mossy Bottom Farm and journey to a nearby metropolis, on a mission to find and return their amnesia-afflicted farmer, the film observes human society from an absurdist perspective. It evokes ideas explored by two of the most distinctive twentieth century filmmakers: the French director Jacques Tati and the Italian director Luis Buñuel.

In one scene the (heavily disguised) sheep sit around a dinner table at a fancy restaurant, pretending to be humans. They must counter their natural animal instincts to mimic the people around them – meaning, for starters, that they resist the urge to chomp on the menu and instead pretend to read it. The scene grows increasingly absurd: a faster paced companion piece to a famous stretch in Tati’s 1967 masterpiece Playtime, when a pretentious modern restaurant becomes a setting to satirise the noisiness of modern times. That Shaun the Sheep restaurant scene is also a little like something out of a Buñuel film – most obviously The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, the director’s 1972 surrealist classic about people who are always arriving for dinner but never get the chance to eat it.

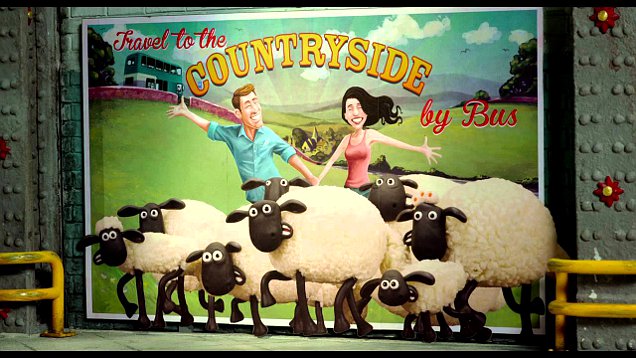

In a clever visual flourish early on, the quick-thinking sheep hide from the villain (an overzealous animal control officer) by bunching up and freezing in front of a billboard with a picture of green pastures on it. When the nefarious animal catcher looks at this picture the villain accepts them as part of the bucolic printed tableau, and the group scuffle off when he looks away. When the villain returns his gaze to the advertisement, the picture is now without the sheep and thus significantly barer; he blinks and does a double take. The influential theorist Jean Baudrillard would have had a field day with this: the natural is manufactured and the manufactured natural, creating a hyperreality where reality and artifice have become indistinguishable.

There’s a lot you can read into this movie, including the Orwellian situation unfolding back at the farm. Shaun successfully dethroned the man in control of the animals’ daily routine, pursuing his dream of a life of leisure. He is heavyhearted to discover however that one power structure (the farmer) has been replaced by another, more oppressive power structure (Mossy Bottom’s party hardy pigs).

Perhaps the best recommendation is simply that the Shaun the Sheep Movie is a joy to watch. The directors show great respect for the audience, in a sense encouraging viewers to direct their own experiences; we can scan the frame for puns and piece together stories within stories. Like in Playtime, the film’s crowning achievement is the mastering of a kind of cinema that, after all these years, has barely even been invented. The European artistes mentioned in this article have had their works praised, vaunted, canonised, hung up and framed in the hallowed halls of academia. We shouldn’t forget Shaun and his pals – even if the film’s posters look kiddish, and even if the sequel proves disappointing.

Shaun the Sheep Move is available to stream on Stan