Why Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse belongs to one of modern cinema’s most exciting movements

Critic Luke Buckmaster explains why the sensational new Spider-Man movie is part of a hugely exciting movement in modern cinema – which has nothing to do with the superhero genre.

Near the beginning of Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse the audience are whooshed through a potted summary of the titular hero’s origins (bitten by a radioactive spider etcetera) in a slab of narration that kicks off with the words “let’s go through this one more time.” That line returns later to describe other iterations of the iconic web-slinger. This film’s high concept twist is that it belongs to a universe (or Spider-verse) where numerous realities exist, each of them containing a different version of the character as well as a different aesthetic with which to view them.

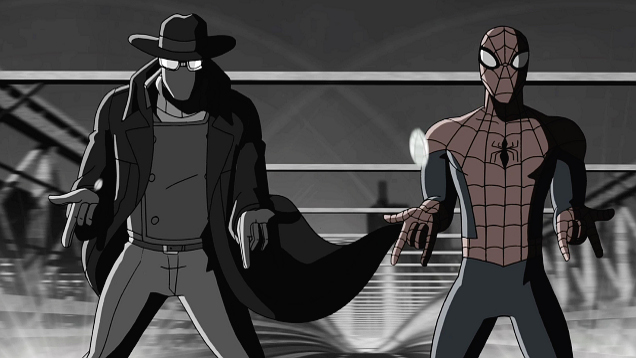

There is a noir Spider-Man voiced by Nicolas Cage, for example – who can only see in black and white, which poses problems for the completion of his Rubik’s Cube – and a Looney Tunes-esque talking pig called Spider-Ham. Co-directed by Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey and Rodney Rothman, Into the Spider-Verse distinguishes itself from other superhero stories by using a hokey plot device (the opening of a portal into different dimensions) not to enable the villain but to riff on the imitable qualities of the hero.

When we hear the “go through this one more time” spiel on the second and third occasion, describing versions of Spider-Man who are not the young protagonist Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) the irony becomes clear: there is no end, no ‘one more’. It is a way for the screenwriters, Phil Lord and Rodney Rothman, to acknowledge pop culture’s infinite cycle and to comment on the myth of origins. At one point when Miles is cutting his teeth as a do-gooder he is even criticised for wearing Spider-Man merch: the genuine article clothed in an imitation of the real thing.

There is a poignant moment in the wake of Spider-Man’s death, after he is sent to the great big cobweb in the sky by the boulder-like villain Kingpin (Liev Schreiber). The world mourns the death of a superhero. Shortly later, however, a different Peter Parker emerges from another dimension and we “go through this one more time.”

This version of the hero crashes through a tombstone with his own name on it: a chilling premonition of his death that actually happened but never was. The underlying message is that Spider-Man cannot die, for the same reason Banksy’s art (which is briefly referenced) will live on far longer than the man/men or woman/women who ‘was’ or ‘is’ Banksy: because the character is based on an idea, and ideas transcend bodies and physical spaces. The concept of the mask is much more powerful than any person who wears it.

This intensely energetic movie belongs to an exciting modern movement. Before we progress: no, I am not referring to superhero movies, which more often than not are intellectually lazy exercises in brand management, with a chilling effectiveness in their ability to stupefy audiences. These recent films offer thrillingly contemporary ideas that go beyond post-modernism (the so-called “culture of quotations”) and intertextuality (the relationship between texts) into a narrative space incorporating multi-dimensional elements.

Can we call this multidimensional modernism? Does that label sound too lofty? If you’re partial to more colloquial language, perhaps we can call it ‘trippy shit that connects and rearranges perceptions of realities’. While filmmakers manipulating impressions of reality is broadly speaking nothing new, these stories are different and hugely relevant to the current times, in which the nature, fabric, and boundaries of the universe are so regularly questioned. The futurist Mark Pesce summed up the mood when he described the current moment as The Last Days of Reality.

It could be argued that “movement” is too strong a word, given unlike great film movements of the past (such as German surrealism and Italian neo-realism) there is no overarching, edifying tone or purpose to this multidimensional modernism. On the other hand perhaps that is another reflection of these intellectually chaotic times.

Many recent films I see as belonging to the movement reflect in some way on commercialism and consumerism, have a proclivity for nostalgia and consider art – and even the universe – in the context of creations within creations. The infinite cycle, the myth of origins. Many incorporate an element of self-critique. Here are six interesting recent examples, all gleaned from film (television can be a separate conversation, with lots of potential for Rick and Morty references).

In her root reality the protagonist of Zootopia is a small bunny. But when she chases a thief through a gated community called Little Rodentia, where various rodents go about day-to-day life in a bustling rodent metropolis, she becomes this universe’s equivalent of a Godzilla-sized beast. Perhaps the point is that we are all too big to grasp our relevance to tiny things, and too tiny to comprehend the size of the universe.

An alien race watched footage of human beings playing video games and misinterpreted it as a declaration of war. One of the forms they assume in order to communicate with humans is the character of Max Headroom, which they project into the sky. Headroom was heralded as the first computer-generated TV host but was in fact an actor in heavy prosthetics pretending to be one. Now he returns as actual CGI, meaning he is a computer-generated image of a real person pretending to be computer generated.

What would happen if characters from Muriel’s Wedding, Grease and BMX Bandits entered the dystopian world of Mad Max? There are many unexpected collisions in this provocative film that mixes cinematic worlds in order to create new incendiary meaning, perfect for a point in time in which everything feels like a remix of a remix. When Lord Humongous speaks with John Howard’s voice, delivering the former PM’s famous ‘we will decide who comes to this country’ speech, fiction has turned shockingly real and reality has merged with make-believe.

A film that exists exclusively inside the LEGO world introduces a universe-realigning twist over an hour into the running time, revealing the nature of God. God is Will Ferrell. The LEGO Movie switches to live action to communicate that the universe we have been observing belongs in a man’s basement, riffing on a classic episode of The Twilight Zone. Is this an art film or a toy commercial?

Belgian video artist David Claerbout and his team of animators re-drew every frame of Disney’s animated classic The Jungle Book in order to remove all human elements. The resulting film has no plot, no story, no dialogue. Does it now become an observational documentary? In a medium based on projections of light and sound, is there any real difference ‘genuine’ animals and hand-drawn ones?

Characters inside a virtual world enter a virtual cinema which turns into The Overlook Hotel, from Stanley Kubrick’s horror classic The Shining. Those who saw Ready Player One on the big screen went to the cinema and watched characters enter a virtual world, then enter a virtual cinema, then enter a virtual reconstruction of an old film, then return to the virtual world, then return to the ‘real’ world – an imagined dystopian future where people consume too much digital media.