Bone-chilling documentary The Social Dilemma will make you rethink social media

What are the consequences of our infatuation with social media? Netflix’s must-see documentary The Social Dilemma may cause you to rethink how you use your phone and computer, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

“Nothing vast enters the life of mortals without a curse”, reads the opening text insert preceding Netflix’s new documentary The Social Dilemma—a quote from Sophocles. Over the course of 94 gooseflesh-raising minutes, director Jeff Orlowski investigates the potentially catastrophic effects of social media networks onto human societies, combining an overarching ‘can’t put the genie back in the bottle’ outlook with a patina of optimism—in the message that there is still time to embrace a more ethical approach to online discourse, although it almost certainly has to come from the top down.

The film’s first major accomplishment was securing a group of insiders keen to speak out against tools they themselves created. Experts include Justin Rosenstein (creator of Facebook’s ‘like’ button), Sandy Parakilas (former Operations Manager for Facebook), Bailey Richardson (one of Instagram’s first employees), legendary tech innovator and computer scientist Jaron Lanier, and Tristan Harris, a former designer ethicist at Google who has argued at length that online platforms exploit psychological vulnerabilities and downgrade human potential.

What is really the product being sold?

Talking points in a whirlwind of tangential subjects (there’s enough material here for a hundred, even a thousand more documentaries) include surveillance capitalism, the deliberately addictive design of social and search platforms, and the grimly compelling question of what—or who—is really the product being sold. Hint: think about what Soylent Green is really made of.

The tone of the film is something akin to assault: a group attack on social media from Silicon Valley hotshots, acting like Tom Cruise in Jerry Maguire—taking an impassioned stand against their own industry and imploring others to follow. The findings are frighteningly compelling, and scary because the film rings true—even if Orlowski’s perspective often ignores historical contexts that might help us put the contemporary situation into perspective.

His attitude seems to be: yes, the world has experienced previous worrying trends, but the scale and extent of the social media experience is unparalleled. It’s hard to argue with that. The director notes for instance that for the first time in human history, a small group of designers and programmers—mostly white men aged between 25 and 35—make changes that impact the lives of billions of people. But no reason to worry, right? It’s not as if Facebook has been busted conducting secret mood experiments on its users.

Feeds provide customized versions of reality

For me the most alarming tangent unpacks a metaphor explored in James Bridle’s excellent book New Dark Age, about how when we look to the cloud (now of course an actual thing above us, as well an intangible digital force all around us) we all see different things. Social and search algorithms cater to our biases and preconceptions, transforming reality into a kind of Rorschach mask, shifting and morphing depending on who is watching.

Imagine if, when we visited a widely trusted news website such as ABC News, each of us saw a different version of the reportage, customized to accommodate our worldview. You should be able to imagine that, says Lanier, “because that’s exactly what’s happening on Facebook; it’s exactly what’s happening on YouTube.”

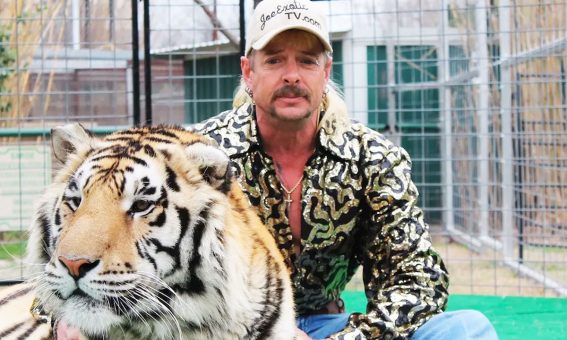

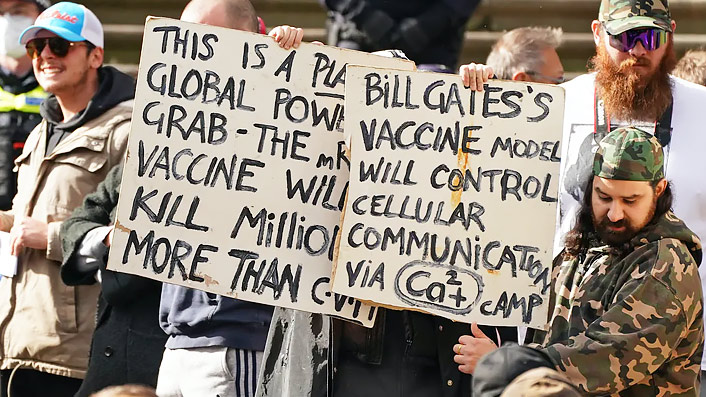

One of the film’s key talking points considers how social media spreads conspiracy theories and misinformation across the world like a poison, corroding people’s ability to think rationally. Not necessarily due to nefarious intent, but rather, notes Harris, because the system operates on “a disinformation for profit business model”, meaning the biggest and easiest profit is made through distribution of unregulated messages. In the current moment, conspiracy theories are spreading faster than ever before—from anti-vaxxing to anti-5G to QAnon and the ‘plandemic’.

Bridle touches on the danger of these unscientific and gallingly irrational perspectives in New Dark Age, giving the process of tumbling down the conspiratorial rabbit hole a name: ‘algorithmic radicalisation’. Noting that engaging with one conspiracy theory empowers the algorithms to promote others into your feed, thus providing “an endless echo chamber of supportive opinion”, Bridle writes:

“What happens when our desire to know more and more about the world collides with a system that will continue to match its answers to any possible question, without resolution?

If you’re searching for support for your views online, you will find it. And moreover, you will be fed a constant stream of validation: more and more information, of a more and more extreme and polarising nature. This is how men’s rights activists graduate to white nationalism, and how disaffected Muslim youths fall towards violent jihadism.”

Everybody is living in their own Truman Show

In addition to propelling a dangerous journey towards extremism that potentially culminates in real world behaviour (as The Social Dilemma chillingly demonstrates) this also risks the creation of a society where nothing is agreed upon as real or true. As Roger McNamee, one of Facebook’s earliest investors, puts it: “The way to think about it is 2.7 billion Truman Shows. Each person has their own reality with their own facts.”

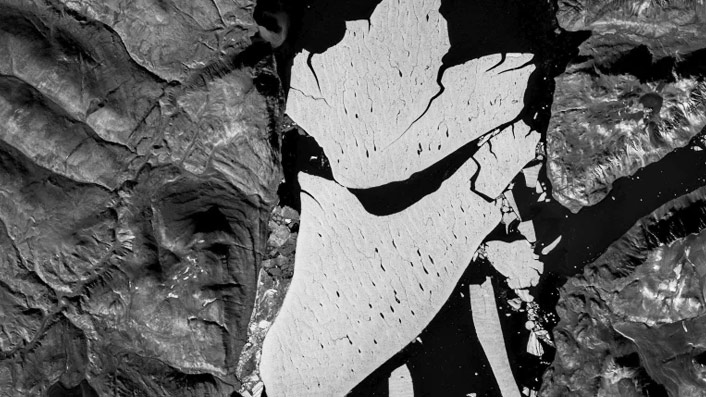

The nature of reality has always been debated, and humans have never—and surely will never—arrive at a consensus worldview. But now the stakes are higher than ever, and social media is amplifying misinformation on an unprecedented scale. If you combine this new era of algorithm-exacerbated delusion with real-world crises such as the pandemic, and existential threats such as the climate crisis, we potentially encounter problems that cannot be properly addressed because they cannot even be recognised as problems.

Decades after global warming was established as a scientific fact, climate deniers are still rampant online—often because they have political allegiances to parties (such as the Liberals, or the Republicans in the U.S.) that do not prioritize—and in fact actively campaign against—climate action. As I write this, unprecedented bushfires rage in California, and word has just come through that a massive chunk has broken off the Arctic’s largest remaining ice shelf, which is roughly 80 kilometres long and 20 kilometres wide (about the size of Paris).

Send these articles (or any others) to a climate denier and they almost certainly won’t make a difference. Online repositories such as Google, Facebook and YouTube offer countless pieces of content allowing them to ‘prove’ the opposite: that climate change is a hoax, or nothing to worry about, or not human-created, or even that it is good for us. We are fed information that allows us—and even encourages us—to live in delusion while brutish reality continues to run its course. Science, reason and compassion are more important than ever—and seem to be in increasingly short supply.

The most chilling section of The Social Dilemma speculates about where unregulated social media platforms, acting in effect as de facto governments, might lead us, dropping words such as “civil war”, “collapse of democracy”, and “autocratic dysfunction.” Cripes. Pleasant weekend viewing this is not. But it’s a must-see documentary and it’s important to have this conversation now. As Tristan Harris, the former ethicist from Google, puts it: “Our technology is going to become more integrated into our lives, not less. The AIs are going to get better at predicting what keeps us on the screen, not worse.”