‘Samson and Delilah’ Interview

Samson and Delilah – now playing in cinemas – takes us deep into the outback to reveal a side of Australia rarely seen on screen. The director, Warwick Thornton, is a cinematographer by trade, who has made the leap to directing because he was starting to starve. “Rather than waiting around for the phone call,” he said, “I decided to start writing films. Writing films that I would like to shoot.” Flicks caught up with Warwick while he was in Auckland and pressed him about his film and how he made it.

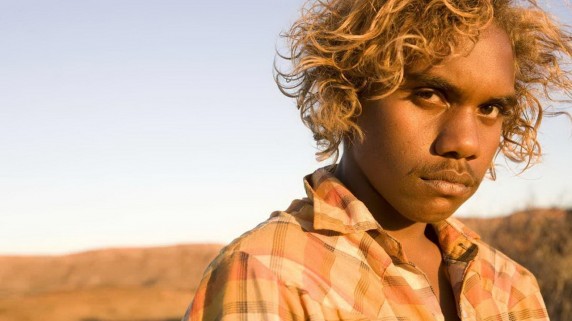

FLICKS: The actors in Samson and Delilah were all first-timers. How did you direct them?

WARWICK THORNTON: It’s not rocket science to teach someone to act. The great thing about people who have never acted before is they’re a blank canvas. They don’t come with their own formulas and their own ways. It’s very easy for you to teach that stuff to them because they’re like a sponge. But when working with 13-year-old kids from these desert communities, the problem is they are incredibly shy and they get incredibly shamed and very quickly embarrassed. Obviously there are many people behind that camera, so you have to break down all of that shyness so that when I say ‘I want you angrier’, or ‘I want you to be faster, smarter, shyer’ – all those kind of simple things – they can just do it without going, ‘Oh, I don’t really want to do this, I am too embarrassed.’ That was the hardest bit.

…which is an obvious benefit of having a small crew.

Yeah, absolutely, and we did that on purpose. I’ve done a lot of films where there’s been 20 trucks parked around the corner, and there’s 150 people for lunch, and there’s a lot of people standing around getting paid doing nothing. I didn’t want that. I wanted a very small personal crew – people who can work in the desert and they ain’t going to whinge and they’re not there just for money. I wanted this really special crew so I chose people that I’ve worked with over the last 20 years. People that I’d like to go with the pub with and shout them beers, you know?

And your brother plays Gonzo. I’ve heard a little bit about him – he sounds like an interesting character.

He’s a ratbag. My brother’s been an alcoholic since he was 17 and sort of living in parks and under bridges and all that sort of stuff. He’d always ask if he could be in one of my films and I’ve always said no. So when I started writing for that character I thought it was a perfect opportunity. But I took it a little bit further than that and I said to him, ‘You can be in a film, I’ve got this character that you’ll be able to play, no worries, but you’ll have to go to rehab and sort out your alcoholism.’ So he did, and three rehabs later, I think he had seven or eight months – he came out sober and then he was on set. It was great to see him sober. But then afterwards he went back to drinking – back in the parks and under the bridge. But, you know, at least he was sober for a while.

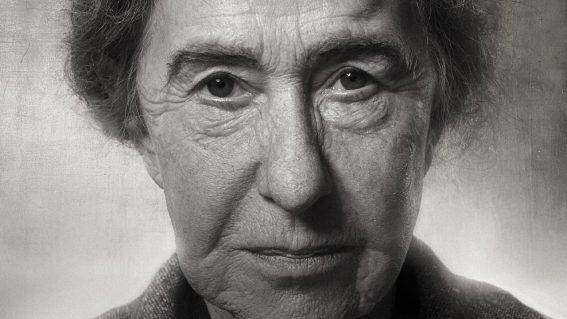

I really liked Mitjili Gibson, as Nana. She had a great face.

Yes, she was raised in the same area that the film is set. And I wrote the character of Nana with Mitjili in mind, because I have worked with her before. I made a little short film called Nana and I made two documentaries with her out in the western desert. She is quite a famous lady out there because she was 35 before she had ever seen her first white person. She lived full out nomadic right into her ’60s.

It’s quite unusual how there isn’t much dialogue in the film, just a lot of looks and glances between the characters. Was that decision made because their acting skills were limited?

No, no, it helped with the acting because they were just running off emotions and that sort of stuff. But that’s the way I see life, you know? When I was a kid, I was so embarrassed. I fell in love with this girl, first love, and I couldn’t talk to her, I couldn’t say anything to her. I was so painfully shy. And you would just want to throw rocks at her, and you want to get her attention but you are too embarrassed to, and see for me that is true love, that is true teenage love.

It’s interesting that the film kind of reveals itself as a love story as it goes on. I really didn’t know much about it at all when I started watching it and I thought it could get really grim and end on a really depressing note, but it was quite uplifting.

Yes, and it was really important for it to be uplifting, and you know, for their love to grow. It is not instant. It is not that sort of Hannah Montana concept of love, when suddenly you see that boy or you see that girl and you walk straight over and you have this huge ten-page monologue about how you feel about that person. It is so untrue. Love grows out of the weirdest places and sometimes you need to use love to survive. You have two kids in trouble and, for survival’s sake, they basically fall in love to look after each other.