Cats, Sonic, Star Wars and the wild new era of the ‘never finished’ film

In an unprecedented move, an updated version of Cats with improved visual effects is arriving in some cinemas. Critic Luke Buckmaster explores a growing trend of films that are never “finished” – a trend that has alarming implications for the future of movie watching.

At the Melbourne premiere of Cats, once the critically lambasted musical had concluded, a friend and colleague of mine told me that he felt so violated by the film that he had to rush to the bar across the road and immediately wash the experience down with hard liquor. “The film looked like it was only partially rendered!” he yelped – looking like a man who’d just sucked on a lemon and chased it with a shot of battery acid – before stepping onto a busy road and narrowly avoiding incoming traffic.

I laughed, bade him goodnight, and thought no more of that comment until last weekend – when I read a news article reporting that Universal had decided, in an unprecedented move, to send cinemas an updated version of Cats containing “improved visual effects.” Cripes. Maybe my friend was right and the damn thing hadn’t been properly rendered. The film’s director, Tom Hooper, seemed to acknowledge as much; it was reportedly at Hooper’s insistence that the studio are distributing the rejigged version.

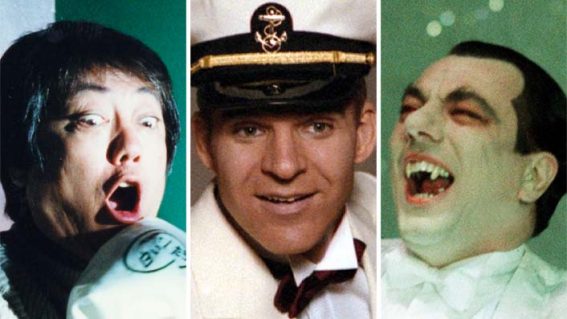

George Lucas – the Star Wars creator and fastidious tinkerer – must have read about this and said to himself: “why didn’t I think of that?” The incident that most famously crystalises Lucas’, erm, passionate work ethic is the Han shot first debacle, which continues to not go away even in the post-Lucas Star Wars era.

It is not the first time the producers of Cats have dropped a stink bomb on the general public, and then, waiting until the ammonium sulfide had dissipated, followed it up with “and here’s take two!” When the film’s first trailer arrived in July, it broke the internet in a very bad way, generating furious agreement among a tortured population that this was a surreal sojourn to cinematic kitty litter land comprised of the stuff nightmares are made of. Hooper and co redesigned the film then delivered a “fixed” trailer.

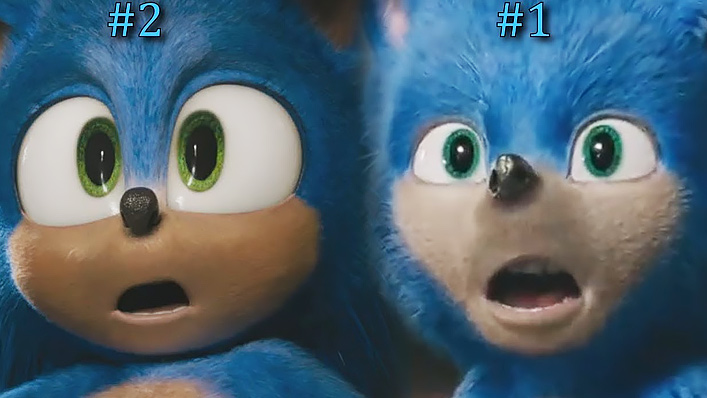

A similar situation befell the Sonic The Hedgehog Movie – in addition to anybody unlucky enough to be within a three block radius of any screen playing it. In its first trailer the beloved spikey video game character resembled a hideous Cronenbergian, Kafkaesque creation with human teeth and a terrible gleam is his eyes.

The film was resigned and a second trailer was greeted with significantly fewer people shielding their faces. Like Cats, the producers used the trailer’s reception as an elaborate focus group, altering aesthetic according to the scale of public outcry.

There is something strange, interesting and potentially alarming going on here, with – when combined with other factors such as the way films are distributed and stored – implications about the nature of film as a “complete” or “finished” form of art. The notion of “motion” in “motion pictures” may be extending – from movement within single images to the flux of a medium that no longer has an end point, moving further and further away from the finality of other arts: the painting forever encased behind glass, or the printed book sitting unalterable on a shelf.

When directors nowadays say “that’s a wrap!” on set, it is purely out of tradition – because those words mean nothing in this age of post-production digital wizardry, when anything can be computer-created and/or reinvented after the fact. Films are now delivered in digital formats and, as the Cats debacle demonstrates, can be uploaded and disseminated via massive files that cinemas download from servers. One of the big questions is not just what the new version of Cats or Sonic or the “Cats Meet Sonic crossover movie (now that’s the stuff of nightmares) looks like, but what happens to the old version.

One of the reasons George Lucas copped so much flak for fiddling with Star Wars was because the release of rejigged new films came with a concerted campaign to remove the old ones. It was impossible for Lucas to eradicate his earlier versions, however, partly because he did not have the time nor the skills required to creep inside all our homes at night and take back our old videos and DVDs – as much as he might want to (sweet dreams, children!).

But physical discs are on the way out, as we all know, replaced by digital/online versions. We are beginning to see what happens when the streaming gatekeepers decide that the content we once took for granted is no longer suitable for our eyes. Because what they giveth they can taketh away.

The recently launched Disney+, for instance, boasts every episode of The Simpsons back catalogue. All, that is, is except for one. The first episode of the third season – Stark Raving Dad, which was infamously voiced by Michael Jackson – is no longer available, consigned to the dustbin of history. The show’s producers decided to pull it from rotation following the release of the HBO documentary Leaving Neverland, which contains extensive allegations of child abuse committed by the late superstar.

This particular example may or may not anger you – but it sets a dangerous precedent. What happens to the work of somebody who runs foul of, well, everything, like Mel Gibson? Does Gibson’s entire oeuvre get deleted – including films he directed, collaborating with a number of other artists including actors, editors, writers and cinematographers, whose hard work could also become, in effect, obliterated from existence?

What happens when a streaming company lobbies a government for financial incentives – and the government says sure, you can have your rebate or your tax offset or your relaxed regulation. But first, how about removing that bit of politically sensitive content? How would we ever get it back?

It doesn’t take much of an imagination to guess where this slippery slope might lead. It is, to mix metaphors, what we call “the thin end of the wedge.” The debacles of Cats and Sonic were borne of ineptitude rather than nefarious intent, and Lucas’ continual tinkering of Star Wars is the folly of a perfectionist gone made. In the future we might not be so lucky; we might have to say goodbye to stuff we once loved, with no recourse to get it back. Then, we will really have a reason to rush across the road and down some liquor.