100 years on, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is just as trippy as ever

The iconic horror-thriller The Cabinet of Dr Caligari is just as insane today as it was 100 years ago, when it first arrived in cinemas. This hugely iconic film has had a massive impact on cinema history, writes Ben McCann from University of Adelaide.

Berlin. February 26 1920. A new silent film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, is released to unsuspecting German audiences and quickly becomes a worldwide sensation. “When will I die?” asks one character to another. “At first dawn” is the chilling reply.

Werner Krauss plays Dr. Caligari, a demented hypnotist who uses a somnambulist, Cesare (Conrad Veidt), to commit horrific murders. But wait! All is not as it seems. In the film’s still stunning twist ending, the whole story is revealed to be the mad ramblings of a mentally ill inmate in a lunatic asylum.

So, 100 years on, why does The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari continue to shock?

Spirits surround us on every side

A milestone in the evolution of the horror genre, Robert Wiene’s brisk 75-minute masterpiece showcased a new cinematic style: German expressionism.

Heavily influenced by new theories about the subjectivity of art, architecture and visual culture, and symptomatic of a nation coming to terms with its post-war neuroses, films like Caligari depicted a highly stylised, distorted vision of the world, full of jagged camera angles, hyper-artificial sets and jerky, robotic acting.

Everything we see feels off-kilter, from the excessive make-up to the highly stylised title cards to alienating close-up shots. Themes of nightmare, paranoia, insanity and murder meet larger concerns about modern dehumanisation and mind-numbing authority.

Right at the start, a menacing iris-in shot (a small black circle opening up to show the whole scene) telegraphs the dread to come, beckoning us into this nightmarish world.

Part scary movie, part avant-garde, part Surrealist fever dream, Caligari still feels profoundly modern.

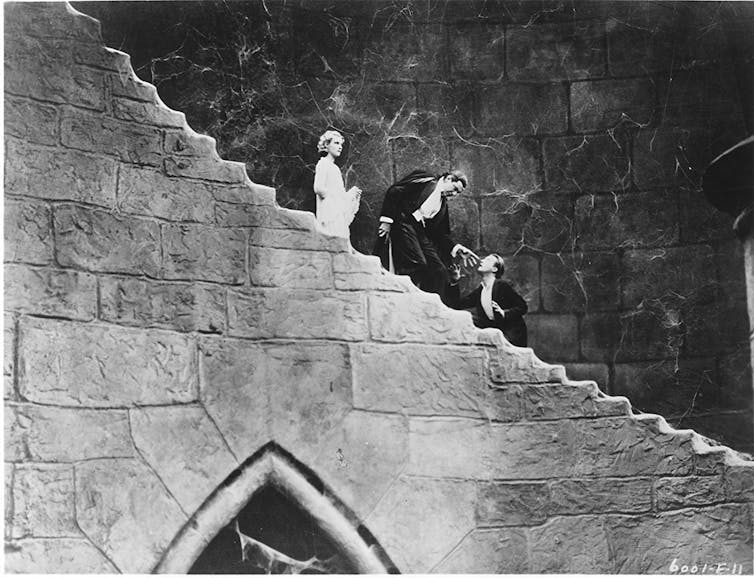

Production designers Walter Reimann, Walter Röhrig and Hermann Warm created a harrowing world of dark alleys, imposing rooftops and vertiginous staircases. Large shadows and occult symbols painted onto whitewashed walls resemble a bizarre mash-up of Picasso, Dalí and Munch.

The film’s use of unreliable narrators, flashbacks and twist endings reminds us of Edgar Allan Poe and the Grimms’ warped fairy tales. The central tyrant figure who exploits a society eager to submit to his will is an appropriate allegory for the German psyche at the time. Cesare is us – the common man, blindly following orders, killing at the behest of others.

Small wonder the film struck a chord with war-weary audiences across Europe.

Judge for yourselves

Critics have had a field day ever since. Siegfried Kracauer persuasively argued Caligari and other horror films released in Weimar-era Germany, like Nosferatu (1922) and Waxworks (1924), subconsciously laid the groundwork for the rise of fascism and Hitler.

Virginia Woolf marvelled at how the set design mirrored the emotions felt by the characters and the audience: “it seemed as if thought could be conveyed by shape more effectively than words”. David Thomson claims it is the very first “mad psychiatrist” movie.

Hollywood also took note: early Universal horror films such as Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931) owe a clear debt to Caligari’s visual texture and brooding menace. The classic noir films of the 1940s share the same DNA – the city is a site of paranoia and hidden dangers, where shadows are everywhere and staircases lead nowhere.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari resonates in other formats too.

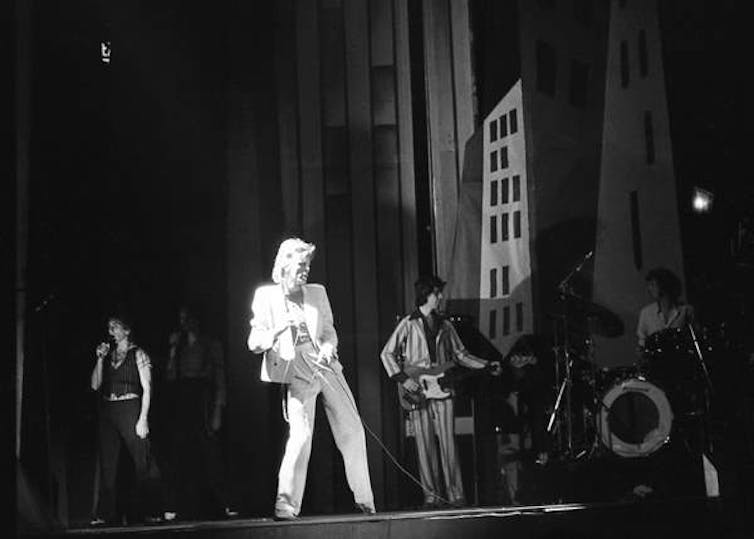

It has been adapted for the stage, turned into an opera, and was screened by the Victoria and Albert Museum as part of the David Bowie is exhibition in 2013. Apparently, Bowie loved the film so much that he asked that the stage sets for his 1974 Diamond Dogs tour capture the spirit of the original.

In the cult 1989 erotic sequel, Dr. Caligari, the granddaughter of the original Caligari performs illegal experiments on her patients at the CIA – the Caligari Insane Asylum.

Wiene’s film continues to echo in contemporary cinema. Its dream-like cityscapes have seeped into virtually every Tim Burton film from Batman (1989) to Corpse Bride (2005). It’s no coincidence Johnny Depp’s Edward Scissorhands is made up to look like Cesare.

And isn’t Martin Scorsese’s much underrated Shutter Island a modern remake, right down to the twist ending, the unstable narration and Ben Kingsley’s shadowy psychiatrist?

Themes of madness, small-town tyranny and zombie-like obedience have remained mainstays of horror films, from The Exorcist (1973) and The Shining (1980) right up to TV series like Hannibal and Twin Peaks.

And it’s clear audiences continue to respond: Caligari remains one of only a handful of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Mr Director, unmask yourself

The great German expressionist filmmakers would eventually disperse.

F.W. Murnau emigrated to Hollywood in search of bigger budgets and more technically ambitious films. Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder fled to Paris to escape the rise of Nazism, eventually ending up in America for long and illustrious careers.

Wiene was not so lucky. He died from cancer at age 65 in 1938, forever shackled to the legacy of his most famous film. But, a century on, Cesare’s ghoulishly staring eyes remain as frightening as ever.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.