Time is an elegant and unconventional documentary about incarceration

You’ve never seen a documentary quite like Time (now on Prime Video), a ruminative and elegantly made film that contemplates incarceration. Here’s critic Luke Buckmaster’s review.

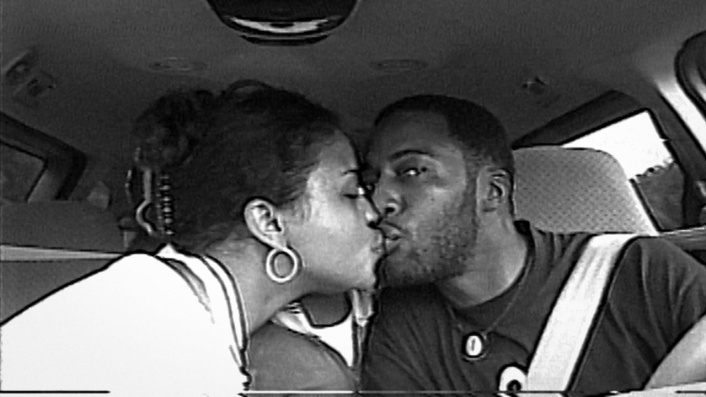

A black-and-white documentary ruminating on the connection between incarceration and the passing of time might sound like a downer—but there is a lovely softness and tenderness in Garrett Bradley’s film, which is threaded with qualities critics tend to describe using words like “lyrical” and “poetic.” Both descriptors apply, I suppose, though Time is also strangely insular and self-contained, setting its scope and limits very carefully and consciously, defined as much by what it is about as what it isn’t.

See also

* All new movies & series on Prime Video

* All new streaming movies & series

The hermetic seal Bradley wraps over the picture screams ‘time capsule’, even when the director switches from old home movies—recorded and presented in 4:3—to present day footage displayed in widescreen. Or perhaps that should be present era footage. As soon as the present is recorded it becomes the past, of course, a consequence of the intractable forward trajectory of our lives and the world around us, and also of film as a medium that sculpts moments into fossils: a mausoleum of moving pictures.

Bradley’s documentary got me thinking about the relationship film has with the passing and recording of time, and made me reach for an old book on my shelf: Laura Mulvey’s Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. In the first chapter I found the quote I was looking for, from the film historian Palo Cherchi Usai, who described moving image preservation as “the science of gradual loss and the art of coping with the consequences.”

The loss reflected on in Time is both gradual and, when you return to its roots, sudden, the lives captured in this film profoundly altered by a bank robbery in Louisiana in the late 90s committed by husband and wife Robert and Sibil Richardson. She received a three and a half year sentence and he—dissuaded by his lawyer from taking a plea deal—received 60 years. And the film is all about coping with the consequences, Robert’s jail time casting a great cloud over the lives of Sibil and their six sons, who grappled with an aching kind of nothingness: no updates; no more information about an upcoming parole hearing; no news of any kind.

The film has hymn-like ambience and the texture of a photo album drained of colour, that wistful monochrome look communicating the absence of profound things—the details, the energy, the vibrancy of moments that should have been memories forged and shared by the whole family. The film’s distinctive look and feel compensates for an elusive approach to virtually everything—including and especially the bank robbery, which Sibil reflects on in broad terms early in the piece, justifying it as such: “desperate people do desperate things; it’s as simple as that.”

There are no reenactments and there is never a question of whether the pair did it. Time is never about guilt or innocence: rather the scale of the sentence (60 years!), the effect it has on family, and the punishment’s context within a prison-industrial system where words like “justice” mean entirely different things depending on race and demographic. Sibil, a public speaker, Christian and self-proclaimed abolitionist, describes the prison system as being “designed just like slavery to tear you apart, and instead of using the whip, they use mother time.”

The film arrives during a period of heightened interest in true crime documentaries, even the best of them generally much more compelled by the crime than the criminal. Bradley finds a different vantage point, prioritizing emotional ambiguity over circumstantial details. But there are drawbacks: she offers few narrative hooks to hold onto, for instance, which makes the experience feel fuzzy in all kinds of ways, and the home video footage is notable not for its dramatic qualities but its ordinariness.

Yet there is unquestionably special about what Bradley has created, even if the crowning accomplishment is tonal. You come out of the film thinking deeper; watching it is almost a form of meditation.