Will the ‘computer screen’ movie be this decade’s ‘found footage’?

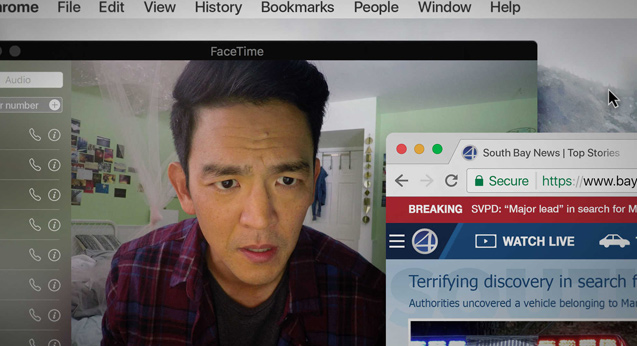

Thriller mystery Searching arrives in cinemas this week starring John Cho as a father who breaks into his missing daughter’s laptop to find out everything he possibly can about her sudden disappearance. The entire film takes place from the perspective of computer screens, which not only demonstrates the crime-solving potential of the Google search engine but also shows just how much of ourselves (and our different selves) exist in online spaces.

It’s not the first ‘computer screen’ movie ever. Blumhouse already made two Skype horror flicks with the Unfriended series. Nacho Vigalondo conducted all sorts of gonzo-magic with the format in the schlocky Elijah Wood thriller Open Windows. Prior to that, short film Noah set Toronto alight with a more down-to-earth story about social (dis)connection.

I never thought I’d be writing this but Timur Bekmambetov, director of Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, recently received some earnest critical shakas for tackling the subgenre. His latest film, Profile, follows a British journalist who dives into the online propaganda machine of the so-called Islamic State.

Bekmambetov believes strongly in the format. He calls it ‘Screenlife’, which is also the name of the production tool he helped developed to tell these kinds of stories. And he’s planning to release a lot more of them.

At this moment in time, ‘Screenlife’ has a freshness to it that gives films like Searching, Unfriended, and Profile a hefty draw. However, it doesn’t take long for innovation to turn into imitation and we’ve only just gotten over the previous fidget spinner of movie gimmicks – the ‘found footage’ subgenre.

The success of 2007 microbudget horror Paranormal Activity and 2008 handycam monster flick Cloverfield helped populate the last decade with a flurry of ‘found footage’ features. With it came a hearty glut of films that used the format in varied and genuinely effective ways: buddy-cop thriller End of Watch, superhero sci-fi Chronicle, ecological disaster drama The Bay, moon landing conspiracy comedy Operation Avalanche, just to name a few.

Unfortunately, the good got lost in the shit blizzard of poorly-executed horror slop like The Gallows, Apollo 18, The Devil Inside, Exists, Chernobyl Diaries, and Paranormal Activity 2, 4 & 3D. Under these quick-buck flicks, the format was used as a means to seek attention and make budgetary cuts. Who needs costly things like decent lighting, proper editing, passable sound design, or a tripod when you can ditch all that and write it off as a creative decision?

This unhealthy marriage of what’s popular vs what’s easy led to oversaturation and the eventual disinterest in ‘found footage’. ‘Screenlife’ could just as easily outstay its welcome, though it has a lot more potential to stay fresh and relevant.

On the surface, Searching may seem like a film shot in 13 days (actually true) with just a couple of webcams (partially true), but there’s a whole orchestra of moving parts essential to the ‘Screenlife’ aspect. Going steps further than Bekmambetov’s streamlined tool, director Aneesh Chaganty brought in the post-production crew weeks before they even hired actors in order to create all the simulated screen work, with Chaganty himself playing every role for reference.

Aneesh Chaganty (left) and John Cho (right)

“We sort of made an animated movie, then shot a live-action film,” Chaganty summarised in this interview with TechCrunch. Once they captured all the performances, the post-team went through it all again making adjustments and refinements, creating a production line that sandwiches on-set filmmaking with two fat slices of animation.

Needless to say, this film wasn’t easy to make – relative or otherwise. It required intense planning with clear execution in order for it to even exist, let alone be a compelling film.

Such a film can still be made with no-name actors and a Paranormal Activity budget – Unfriended exists, after all – but the format demands some kind of coordination between footage and interface. In other words, it’s not as easy as shaking a camera, screaming into a dimly lit warehouse, and slapping a Blumhouse sticker on the poster.

That lack of ease is what could prevent ‘Screenlife’ from cheap oversaturation. Additionally, given the forever-growing nature of technology, the subgenre can grow with it to avoid the staleness that crept up on ‘found footage’.

Social platforms are just as expansive. There’s Skype, Facebook, Messenger, Snapchat, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, Twitch, Facetime, Soundcloud – that’s just a handful of the online tools at the human race’s disposal. Then there’s the likes of Vine, Chat Roulette, Bebo, My Space, and other ghosts of social media past. Who knows what the future holds for virtual friend-making.

The only concerning caveat comes with how audiences watch movies. With more people ingesting films on their own computer screens now more than ever, the incentive of watching a ‘computer screen’ film away from your computer screen may prove to be at odds with general consumers.

Having said that, a moment in Searching caught me somewhat overwhelmed by the sight of that default green hill wallpaper on the big screen. That boring lump of grass revealed flakes of nostalgic memories from my teenagehood, so to have it engulf my entire vision felt oddly comforting. I wouldn’t have gotten that feeling from my iPad.

That’s the ultimate difference between the two subgenres. While ‘found footage’ reflects a medium that reflects life, ‘Screenlife’ simply reflects life – albeit a modern, first-world, technological, interconnected one. We don’t just passively watch screens; we constantly interact with them as a means of communication which, in turn, has grown new forms of human behaviour.

There’s a moment in Searching where John Cho’s character types a message, pauses, deletes the text, and writes something different before sending it to his daughter. Essentially, you’re just watching words on a screen, but it’s an action that – in context – feels extraordinarily relatable and human. ‘Screenlife’ depicts this new language of ours, and there are exciting opportunities to explore it in cinema.