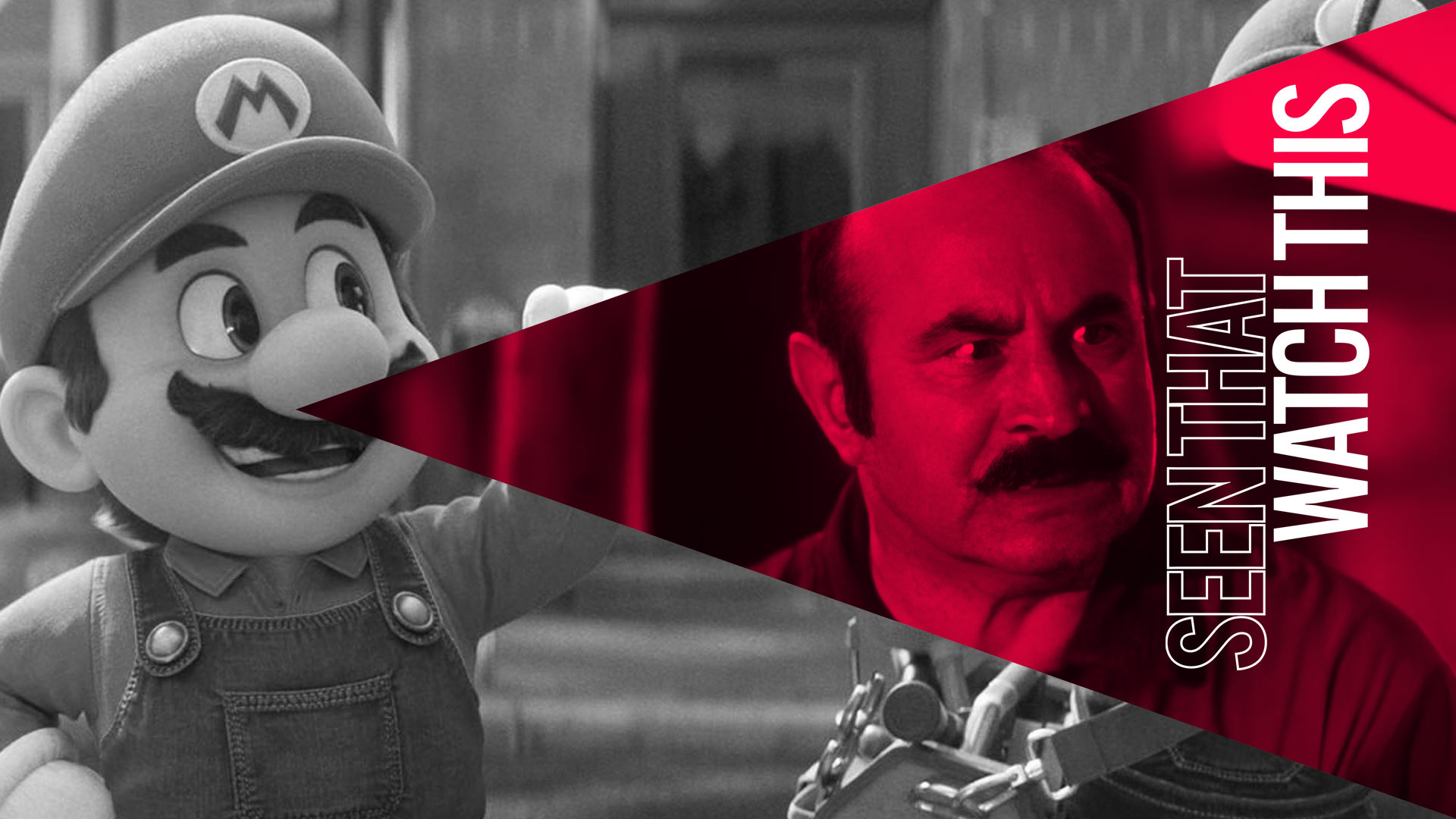

Which Mario movie is better: the new one, or the crazy, weird old one?

Seen That? Watch This is a weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, the shiny new Mario movie is held up against the grimy 1993 flop Super Mario Bros.

Super Mario Bros. (2023)

What’s better: a messily creative movie that makes wild and dumb decisions, or a safeguarded exercise in IP regurgitation with no original bones in its body? 1993’s legendarily bad Super Mario Bros. movie, filmed in live action with Bob Hoskins and John Leguizamo playing the titular characters, is one of those lunatics-running-the-asylum productions that made many wonder: what on earth were they thinking?

The new movie, presented in a gloss-lacquered animated aesthetic bright as boiled lollies, makes one wonder no such thing. There’s no doubt what the producers were thinking: don’t upset the apple cart; don’t destabilize the brand; don’t be bold. Everything about this sludge of risk-averse goop (co-directed by Aaron Horvath and Michael Jelenic) feels streamlined, homogenised, focus group-tested. There’s no life in it; none of the joys of human imperfection. Comparing the old and new Mario movies is an interesting case study in very different modus operandi producing chalk-and-cheese outcomes: one messy and full of creative mayhem, the other back rows-oriented pap.

Both begin with a prologue introducing a bizarro magical world (where the bulk of the story takes place) followed by a second prologue showing Mario and Luigi going about their business as plumbers in Brooklyn. The momentum of the 90s movie (directed by Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel) stalls before it even properly begins, with Mario (Hoskins) and Luigi (Leguizamo) loafing about on the street after their van breaks down and they’re beaten to a job by a competitor. Mario complains about the cost of bottled water—not exactly a valiant early moment for the hero—and Luigi is smitten by an archeology student he meets on the street: Samantha Mathis’ Daisy.

Super Mario Bros. (1993)

In the new movie, the brothers have recently launched a business and shelled out for a TV commercial, playing up to their Italian heritage with knowingly thick accents. Here their race to attend a job is captured in a single shot homaging side-scrolling video games, the virtual camera positioned on the street and tracking action from left to the right. This embellishment is a fun, self-conscious touch, and my favourite part of the movie.

The overalls-clad brothers then (in both productions) enter liminal space by way of a green tunnel marking the threshold from one world to the next. In the new film they’re spat out into the Mushroom Kingdom: a world of rainbow colours and shiny squidgy-looking things. In the other they arrive in Dinohattan—an alternate version of Manhattan located in a parallel dimension created by the meteorite that (seemingly) eliminated all the dinosaurs. There’s many differences between these two movies, but none more telling than how these respective alternate worlds were imagined and designed.

The twinkling Mushroom Kingdom is very cuddly and very game-y. The animation is supposedly cutting edge, intended to create the sort of sculpted cinematic images harder to execute in games, where the virtual camera is controlled by the player. And yet some recent games have struck me as far more impressive visually. For instance the PS5 third-person, piercingly bright platformer Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart creates sensational visual fractures through a “Rift Tether” mechanic that conjures portals the player can swing through.

Dinohattan on the other hand is dark and dystopian, with a junky steampunk aesthetic. The vehicles are pretty freakin’ weird (recalling the vehicular madness of Mad Max and The Cars That Ate Paris) and the streets have Blade Runner-esque bleakness, suffused with an authoritarian aura that reminded me of the Biff Tannen-ruled alternate 1985 in Back to the Future 2. Here the tyrannical ruler is President Koopa, played by Dennis Hopper with his trademark shit-eating snarl (albeit very far from the actor’s best or most outrageous performance). The plushie-like villain in the new movie, Bowser, is voiced by Jack Black—the sort of casting that makes you think “oh, that makes sense.” Nobody ever said anything about the first movie made sense. Not even the odd tagline it was advertised with: “This Ain’t No Game.”

Narratively speaking both films crash and careen, with stories involving Mario and Luigi rescuing Princess Daisy and Bowser/President Koopa potentially crossing over into the “real” world, like Flynn and his minions in the Tron movies. In Mario ‘23, the plot is a coathanger for splashy setpieces, including Mario duking it out with Donkey Kong and a race down Rainbow Road. In Mario ‘93 the plot builds up to the brothers arriving at President Koopa’s tower to rescue Daisy. This stretch embraces the long history of verticality in video games: a literal levelling-up. Like the rest of the film the finale is, frustratingly, both chaotic and casually paced.

The set and character design, however, is an imaginative triumph. The aforementioned environments are dank and ominously atmospheric; you can almost feel the steam rising up from the sewers. And Koopa’s henchmen are something else: very tall, and dressed in military garb, with disproportionately tiny lizard-like heads. Once seen, never forgotten. The new movie is bad: but the old one is weirdly, wildly, legendarily bad. I know which one I prefer.