The amazing cynicism of Rocko’s Modern Life

With a movie version of the classic 90s cartoon Rocko’s Modern Life set to arrive on Netflix, critic Luke Buckmaster revisits the show to see how it holds up. What he found blew his mind.

One weird side effect of the current craze of nostalgia-mongering is that sometimes this cycle of old-is-new-again throws up something you never entertained the idea of seeing again. The other day when scrolling through my social media feeds, for instance, a face from my distant past leapt back into my mind like visions from an acid trip. The last time I thought of this person – well, animal, actually, of the anthropomorphised variety – it was a very long time ago; my pubescent self might have been nursing a Tamagotchi or prodding my first pimple.

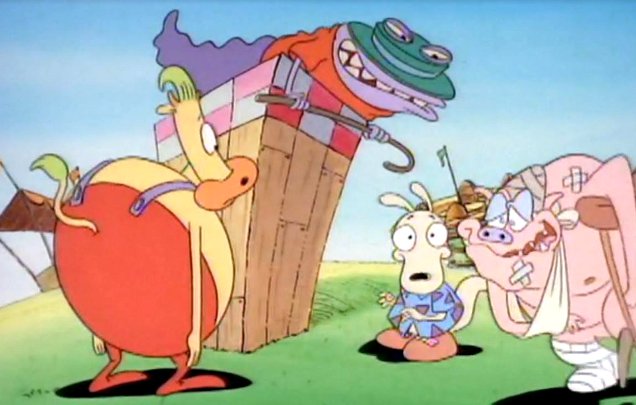

I am referring to Rocko, the protagonist from Rocko’s Modern Life – an animated Nickelodeon sitcom that launched in 1993, which according to recent reports has a movie adaptation heading to Netflix. I am ashamed to admit I had completely forgotten that Rocko is a fellow Australian; a wallaby in fact (in my defence, he certainly doesn’t look like like one). I also found myself unable to recall a single plotline…only fragments – such as the protagonist and his pal Heffer eating ice cream or sitting on the couch watching the tube.

All this begged the question: what is the show actually like? Is it any good? Returning to content loved as a youngster to watch again through an adult lens is a fraught exercise, often resulting in intense disappointment.

But, rewatching the first two seasons of Rocko’s Modern Life, I rediscovered an amazingly cynical show: weird, wild, bawdy and coarse, architectured with a thoroughly interesting and perhaps perverse approach to the concept of family entertainment. Instead of smoothing over all the edges and creating content inoffensive to everybody, as the thinking generally goes, this vision of family entertainment involves creating edgy jokes that resonate with adults – with the assumption that younger viewers won’t get them or appreciate them on the same level.

Throughout the show there are tonnes of drug references, stacks of innuendo, loads of violence, a sadistic doctor, various kinds of deaths, a plot line that sees Rocko briefly employed as a phone sex operator, and many anti-corporate and anti-capitalist messages. These last ones are the most interesting, communicating to youth a message to be sceptical about the world around them – not just in specific situations, but even sceptical about the underpinning principles of consumer-driven society.

One episode (ep nine, season one) contains the most cynical depiction of an amusement park I think I have ever seen. Rocko and Heffer pay top dollar for admission into ‘Slippy’s Rides O’Plenty’, given the assurance from a frog-like thing at the front gate (presumably Slippy) that they will experience “fine food, fast rides and some challenging games,” and that “no-one leaves without a smile.” Immediately after that line is delivered a happy customer walks into the frame looking terribly beaten, hobbling on crutches with his arm in a sling and bandages plastered all over him. He does indeed muster a smile. When he tries to make a thumbs up gesture, this poor wretched thing’s thumb falls off and the stump starts spitting blood.

The pair enter Slippy’s broken-down shithole of a place and encounter a horrible set of experiences, which satirise corporate greed and the making of a quick and dirty buck. The ‘Chemical Toss’ attraction allows people to hurl test tubes full of dangerous chemicals. The ‘Oil Spill’ is exactly what it sounds like. The ‘Elevator to Hell’ sends people plummeting into a pit of fire below the ground (from which the devil emerges). The seats on the merry-go-round are made of dead animals, a toilet, a washing machine and an electric chair.

Instead of winning anything from the claw machine, the claw actually manages to come out from behind the glass and steal Rocko’s watch, which it adds to its prize pool. You play, we keep. A log ride spits Rocko and Heffer into raw sewerage and almost slices them in half with a sawmill. The dodgem cars result in several injuries, and a visit from an ambulance.

In another episode, titled Jet Stream (ep 3, season one) Rocko and Heffer visit the airport. Heffer is petrified about flying but is comforted by a staff member who describes the experience of using this particular airline as one in which the company embraces its customers with “loving arms.”

We catch a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what happens to the pair’s luggage: it is set on fire, smashed and shot out of a rocket. When they board the plane, first class is amazing – but coach, where they end up, is as filthy as a trash-strewn barnyard and crammed full of ugly and angry people. Before they take off the pilot makes an announcement: “I tend to black out at higher elevations.”

Like in the carnie episode, great horror awaits. Throughout the show the writers present a reasonably common scenario – like flying on a plane, getting a new job, going to the doctor or buying a new appliance – then imagine pretty much the worst thing that could possibly happen, just shy of death (which actually does happen, but not to the main characters – although in one episode Heffer dies and comes back to life). If this sounds like an onslaught of constant downers, well, it is – but the writing has wit and flair, and the show is presented in a wonky, drunken kind of aesthetic that is thoroughly weird and distinctive. I think I love it.

How could I possibly have forgotten these deranged plotlines? I don’t know – but I do know that, as somebody who is sometimes described as a cynical person, I now I have a pre-prepared retort: “I’m not cynical, I’ve just seen Rocko’s Modern Life.”