5 great movies that unfold in real-time, to watch after Hijack

Seen That? Watch This is a column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, inspired by the plane-based hostage drama Hijack, he revisits some of the greatest movies that unfold in real-time.

Can you guess what happens to the plane in Idris Elba’s new show, Hijack? En route from Dubai to London, it’s no ordinary flight, taken control of by hijackers whose reasons are initially unclear. The way in which it unfolds, however, is ordinary, in the sense it unravels in real-time, an hour for the characters equalling an hour for the audience.

The series revolves around Elba’s Sam Nelson, a passenger who just happens to be a professional negotiator, attempting to resolve the situation via strategic thinking and good old fashioned conversation. It does a pretty good job sustaining tension in a format that doesn’t allow the story to take big jumps forward in time. The “real-time” concept isn’t new, and, in fact, as the below list demonstrates, most of the best applications of it, cinematically speaking, belong to decades past.

Rope (1948)

Hitchcock thrillers never got more commonplace, more everyday, more relatable. A couple of friends host a party and—as was the fashion at the time—decide to serve dinner on a trunk containing the corpse of a mate they just murdered. Based on Patrick Hamilton’s play of the same name, Rope begins with the dirty deed, showing visions of a man being strangled, the eponymous object around his neck (poor Dick Hogan, the actor who plays the victim, stars in the film for approximately four seconds). One of the killers, Farley Granger’s Phillip, is angsty and self-doubting, while the other, John Dall’s Brandon, is sickeningly smug, quick to boast about having committed “the perfect murder.” Perfect, that is, until old mate James Stewart arrives on the scene as the almost supernaturally perceptive Rupert Cadell.

The dialogue flows beautifully, building conflicting personalities that eventually bring the drama to a head. Hitchcock embraced the film’s theatrical origins by staging it as one continuous single take, concealing a small number of cuts. The creepiest thing about Rope isn’t the act of killing, or even the killers per se, but the intellectualisation of murder they use to justify it.

High Noon (1952)

“Do not forsake me oh my darlin’, on this my wedding day…” These famous words open Fred Zinnemann’s convention-breaking western, commencing a famous song that’s catchy in an old-timey way and also an emotional projection of the protagonist’s mindframe. Gary Cooper’s Will Kane is the sheriff of a backwater town called Hadleyville, newly married to Grace Kelly’s Amy. Their celebrations are cut short when news spreads that a vicious outlaw, intent on killing Kane, has been pardoned and is on board the noon train.

The impending arrival of Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) looms over the film. The plot is lean: Kane, an exemplary sheriff, goes around town attempting to rustle up support from men who one by one look the other way. Whereas most westerns embrace a “shoot first, talk later” approach, this one opts for something more meaningful, fine-tuning its moral messaging and interrogating the values of small town America.

12 Angry Men (1957)

One of the great single setting films has lost none of its power or relevance. Sidney Lumet’s classic legal drama skewers the American j̶u̶s̶t̶i̶c̶e̶ court system by illustrating its pitfalls and weaknesses, while offering a patina of hope in the form of an individual taking seriously the concept of reasonable doubt. On a stinking hot day (though the film is in monochrome, so the heat doesn’t entirely register) a dozen jurors are tasked with determining the fate of a poor young boy charged with murder, who will go to death row if convicted.

The case seems cut-and-dried, But one highly intelligent and empathetic juror, perfectly played by Henry Fonda, isn’t entirely convinced and starts chipping away at previously held assumptions. Reginald Rose’s script makes their conversations believable and yet theatrically pleasing. One by one the others change their minds; the film is an ode to rational thinking and critical enquiry.

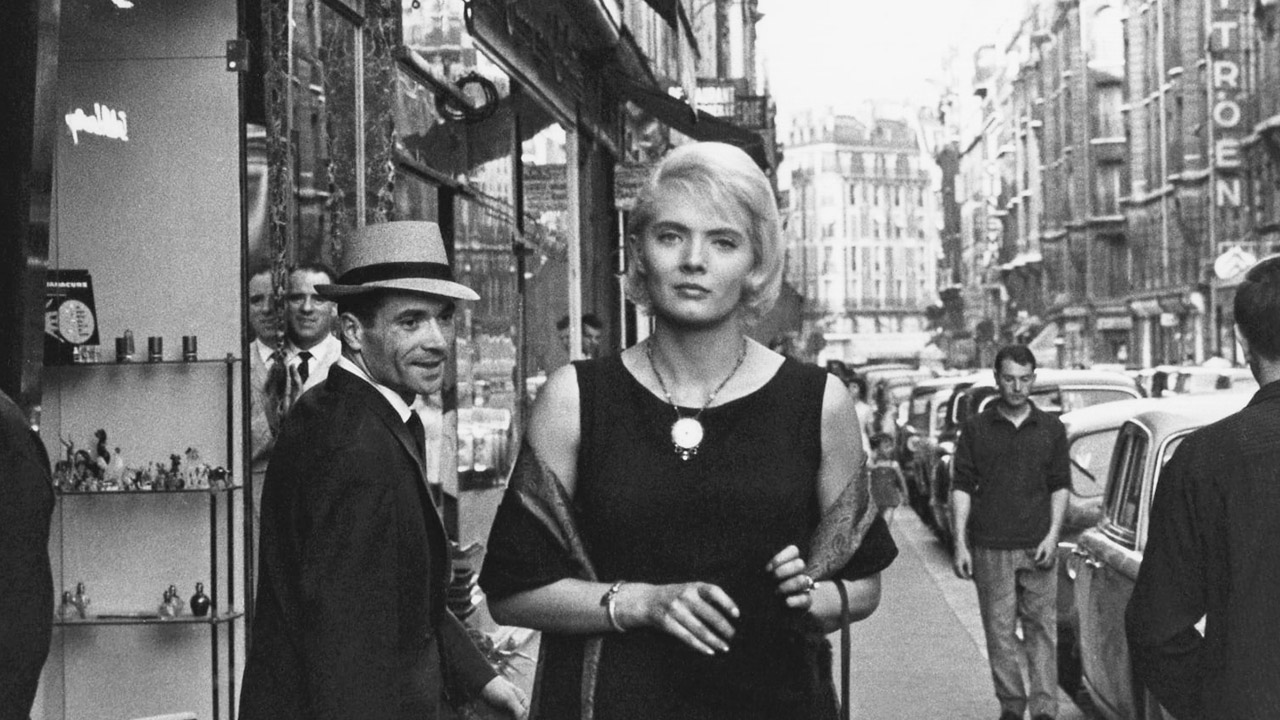

Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

A woman receives a tarot card reading, goes for a walk, visits a cafe, catches up with a friend, catches a taxi home, hangs out, goes for a walk, visits a shop or two. Cléo from 5 to 7 doesn’t sound like riveting drama, but this is an Agnès Varda production, and in fact one of the auteur’s best, radiating style. It has a spritzy lightheaded energy: the cinematic equivalent of popping a champagne bottle. Corinne Marchand is unforgettably cool as the titular character, anxious about her health, and grappling with an underlying sadness that seems to be wrapped up in her beauty.

“I can’t see my own fears. I think others look at me; I look at no-one but myself,” her internal monologue comments, as she gazes at a reflection of herself. Set in Paris in the early 60s, the film is a chic ode to cosmopolitan life, full of the buzz and thrum of city energy.

Russian Ark (2002)

There’s never been anything quite like Alexander Sokurov’s single take masterpiece, which proposes a different form of filmmaking: part movie, part theatre and part museum tour, unfolding in first-person perspective. We hear the protagonist, or narrator, but don’t see him: his eyes are the camera, and the camera his eyes. “Judging by their clothes, this must be the 1800s. Where are they rushing to?” he begins, referencing well-dressed people he follows into a palace (in real-life, Saint Petersburg’s Heritage Museum) where the rest of the film takes place.

In one unbroken and beautifully explorative shot, he/we are guided by the Marquis (Sergey Dreiden) through 33 rooms, filled with opulent art and sculptures, each presenting a different period of Russian history. Is time folding in on itself? Is it a dream? An elaborate play for an audience of one? The “real” in “real-time” has really never been so strange, so dream-like.