Lovecraftian horror movie Glorious features a glory hole voiced by JK Simmons

It’s just your average, garden variety film about a man trapped in a toilet cubicle, accompanied by a god talking to him through a glory hole. Rory Doherty reviews the outrageous but annoyingly self-aware Glorious.

There’s a particular kind of creative mind that’s endlessly fascinating. It’s the type possessed by Glorious director Rebekah McKendry and writers Todd Rigney, Joshua Hull and David Ian McKendry, who probably tried to come up with a post-COVID feature that required minimal actors and locations, where whatever big names they could get would have to feature in a reduced capacity.

Apparently, such creative limitations resulted in the most outlandish high concept premise you’ll hear all year: a film about a man on the brink of psychosis, who finds himself trapped in a life-or-death cosmic horror situation with an eldritch god hidden in a rest stop toilet cubicle. Who talks to him through a glory hole. Voiced by Academy Award winner JK Simmons.

It’s a story idea that assures Glorious more curious eyes and, potentially, an audience likelier to forgive any dips in quality—we’re all rooting for that premise to work. While McKendry et al. do a stellar job transplanting the ideas behind HP Lovecraft’s work into a distinctly crass setting, it’s impossible to ignore how underwhelming great swathes of the writing can feel. Unlike the non-Euclidean monstrosities that earn the moniker Lovecraftian, the emotional journey of Glorious is something we’ve all seen before.

Wes (Ryan Kwanten) is looking worse-for-wear when he pulls into a rest stop, reeling from a curiously ill-defined breakup and ready to either turn his life around or spiral into disrepair. It’s here he encounters the bassy-yet-folksy tones of JK Simmons, who encounters a fairly novel ice-breaking dilemma—how do you convince someone you’re a Lovecraftian god?

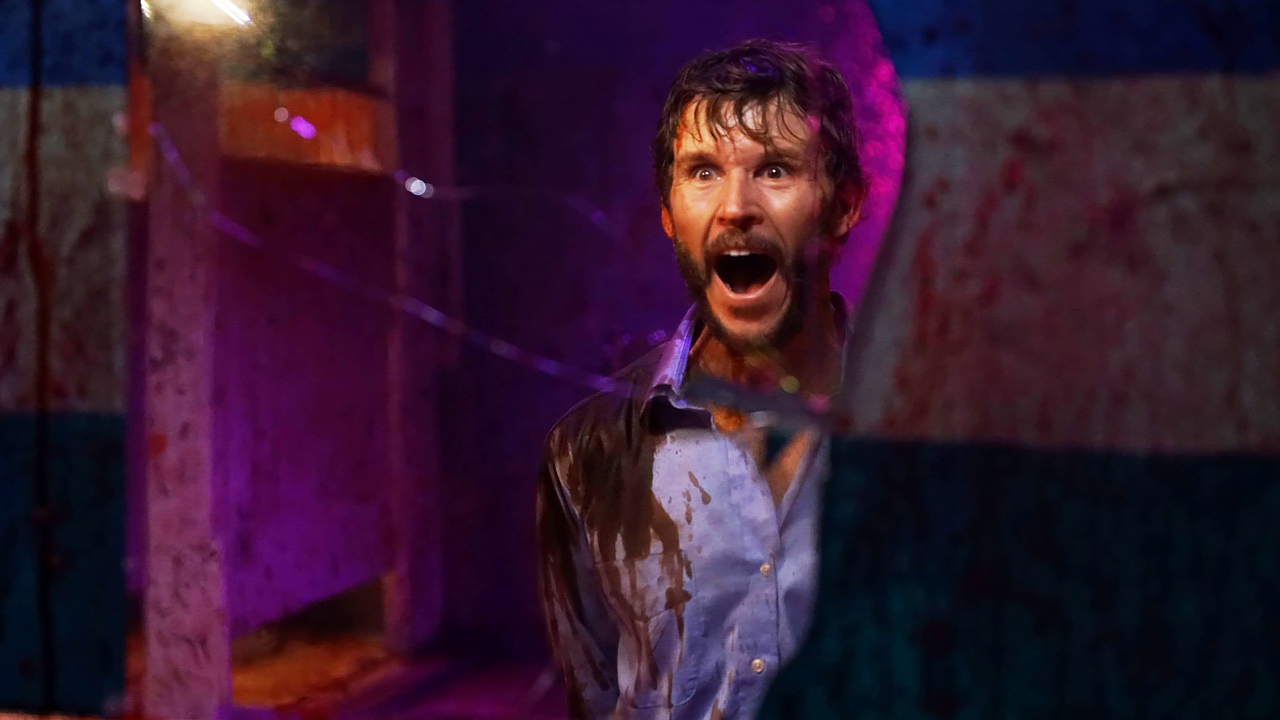

The bathroom striplights take on the purple-pink hues that Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond ensured we associate with Lovecraft, and Wes finds he can only escape the bathroom through hallucinations of his ex Brenda (Sylvia Grace Crim). After a decent amount of time discussing the bodily excretions that have already made contact with Wes’ body and clothes, and a few thwarted escape attempts, we settle into the meat of the story: primarily a lot of treading water before the stakes are incrementally raised or exposition revealed.

It’s a cheap critique to say that a feature film should have been a short instead, but seeing as Lovecraft’s work can be interpreted and updated in an exhaustless myriad of ways, the fact that Glorious spends so long repeating its scant plot beats suggests the writers could have developed their story to fashion a more engaging journey.

The heightened premise results in an irritating tendency for the script to show self-awareness for how ridiculous its story is. Several times, characters will utter lines that amount to “Isn’t this wild?”—a thought supposed to be articulated by the audience, not the film they’re watching.

Glorious ’ job is to be wild, to upend expectations and push beyond the familiar—not to express self-satisfaction about how wild the idea behind it is. There is a moment of misdirection, whereby it looks as if our central glory hole will become pivotal to the furthering of the plot—but all we get is a joke about how stupid such a plot point would be. Does Glorious call out the crassness of audience’s expectations because its creators couldn’t find a way to earnestly pull them off?

The film’s partial hollowness is softened by how eye-catching it looks and feels. Multicolour body-horror graffiti becomes animated to tell the caveman-art mythology behind Simmons’ cubicle’d creature, and a couple shots notwithstanding, the CG graphics meld with practical effects and production design to create a claustrophobic sense of othering within a familiar, if grim, environment. When vaporous flecks of blood silently raining down on Wes are followed up by a treasured photograph being washed away by a wave of blood, McKendry’s talents as a visual horror storyteller are clear. She works a compelling performance out of Kwanten, whose attempts to ground himself always land on the right side of delirious.

By the time Wes is manipulated into a perverse sacrifice, a central idea has coalesced: that the overlap between stories of masculine inadequacy and the human response to cosmic monstrosities is vast and legitimate. It’s unclear whether a last-minute reveal adds to or undermines the themes that have been unravelling for the previous 70 minutes, but it gives more to muse over than most comparable low-budget horror movies. Glorious is a big swing, and while it ultimately feels like a miss, the swing itself is curious enough to justify our morbidibly gaze.