Happy Sad Man explores troubled masculinity with much-needed intimacy and variety

Troubled masculinity is a complex and often debated subject. A new Australian documentary, writes critic Sarah Ward (reporting from the Adelaide Film Festival) approaches the topic with care and sensitivity.

“I find masculinity very banal, really,” says Sydney artist David Capra. “It’s not very interesting to me.” David is one of five men featured in Australian documentary Happy Sad Man, which explores the very topic that he finds boring and routine. While one might hope that such sentiments travel from his lips to the world at large – or, at least, throughout the filmmaking realm – the movie that relays his tale proves an exception to the usual male-dominated story. The latest effort from I Am Eleven filmmaker Genevieve Bailey boasts something that accounts of troubled masculinity so often lack: not just intimacy, but variety.

Variety might be the spice of life, but it is rarely a factor in cinematic tales of men with mental stress, inner demons or internal woes. Walk into a multiplex and it’s likely that you’ll walk into a film that touches upon the topic, with First Man, Venom and A Star Is Born just the latest examples. Although the individual details change, the same basic story is still writ large across the big screen with frequency. Indeed, heroic, successful, brave or otherwise supposedly worthy men grappling with their worries is the quintessential narrative that humanity keeps trading in.

Enshrining one specific story into our consciousness has ramifications, however. Popular culture’s vision of struggling men – and of men in general – fits such a standard type that actually fitting that type is one of the things that men are struggling with. In Happy Sad Man, the fact that Bailey’s five subjects all deviate from the stereotypical idea of manhood sits at the core of their individual journeys. They’re all happy defying the norm, but they’d be happier still if there was no such concept of normal masculinity, and if the notion wasn’t held up as an idyll to aspire to.

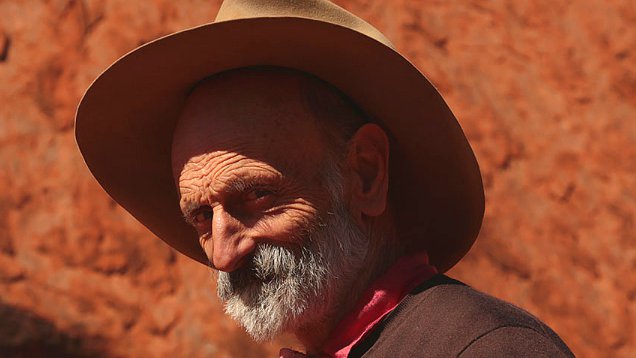

Bailey’s documentary finds its spark in its most prominent figure, self-described “first hippie on the south coast of New South Wales”, John. After making the short From Bombay to Broken Hill about him in 2002, the filmmaker was inspired to share not just more of his story, but more of what makes the eccentric, nomadic musician tick. Bailey also adopts John’s way of looking at the world, thematically rather than visually. “The world’s not totally tragic,” he explains. “The world’s not totally bloody marvelous either. Or it is those things, and every shade in-between and somewhere in the middle.”

John’s plight is one of ups and downs; of forging his own path, navigating complex family dynamics as both a child and an adult, and confronting mental illness. While he earns the bulk of the feature’s attention, Happy Sad Man intertwines his tale with the lives of four other men who also eschew easy categorisation.

The aforementioned David makes art dedicated to his dachshund Tina – including a wet dog perfume – which helps him cope with his anxiety. War photographer Jake has chronicled the heart of combat, yet finds himself less at ease then he returns to his usual existence. Ex-New Zealander Grant has surfed the wave that is bipolar disorder, and founded both the OneWave movement and Fluro Friday surfing sessions to encourage conversations about mental health. And then there’s Victorian farmer Ivan, who travels throughout rural regions to give other men someone to talk to.

Individually, each of these men is happy and sad. They’re both and neither and, as John would describe, they’re also every shade in-between. Viewed together in a mood-driven documentary, they help Bailey make a compelling argument that masculinity is a wide-ranging and evolving concept.

That’s a logical, common-sense notion that shouldn’t need espousing, but it’s one that comes into sharp focus simply by surveying the lives of men who don’t adhere to society’s cookie-cutter standard. There’s no better case for diversity among the qualities associated with being male – strengths, flaws and all – than seeing that diversity in action.

That said, Happy Sad Man remains a patchwork piece; a composite portrait that paints a bigger picture with insight and affection, but often presents more than it probes. Chronicling first and drawing connections second, Bailey also prominently inserts herself into proceedings, sometimes taking focus away from her subjects — although the power of the communal story she’s telling always remains apparent.

Of course, that Happy Sad Man proves an imperfect documentary about masculinity’s imperfections feels apt – like theme, like film. Aesthetically, Bailey’s highly personal approach suits the material, with naturalism and intimacy splashed across every frame. And really, seeing a variety of Australian men live their lives, embrace their individuality, tackle mental health and flout the generally accepted masculine ideal should be everyone’s idea of realism.