Bali 2002 takes a scattershot look at the relationship between Australia and Indonesia

Being based on real, tragic events that still loom large in the memories of many Australians, Bali 2002 seemingly can’t take many risks in telling its traumatic story. Eliza Janssen wishes the miniseries had more to say about Australia’s tourist impact on Bali.

Memorialising the 20th anniversary of the Bali bombings that killed 202 people and injured 209 more, Bali 2002 doesn’t indulge in many period-accurate details. The fashion could be spotted in any tourist destination today; the previous year’s attacks on the World Trade Center are never mentioned; and the music at Kuta’s Sari Club is thudding royalty-free beats.

Except for one choice soundtrack selection—Vanessa Amorosi’s Absolutely Everybody. With its humanistic lyrics and exhilarating chorus (“everybody breathes and everybody needs/absolutely everybody!”), the song is a sugary sweet microcosm of the nations-wide survival and healing we’re in for here.

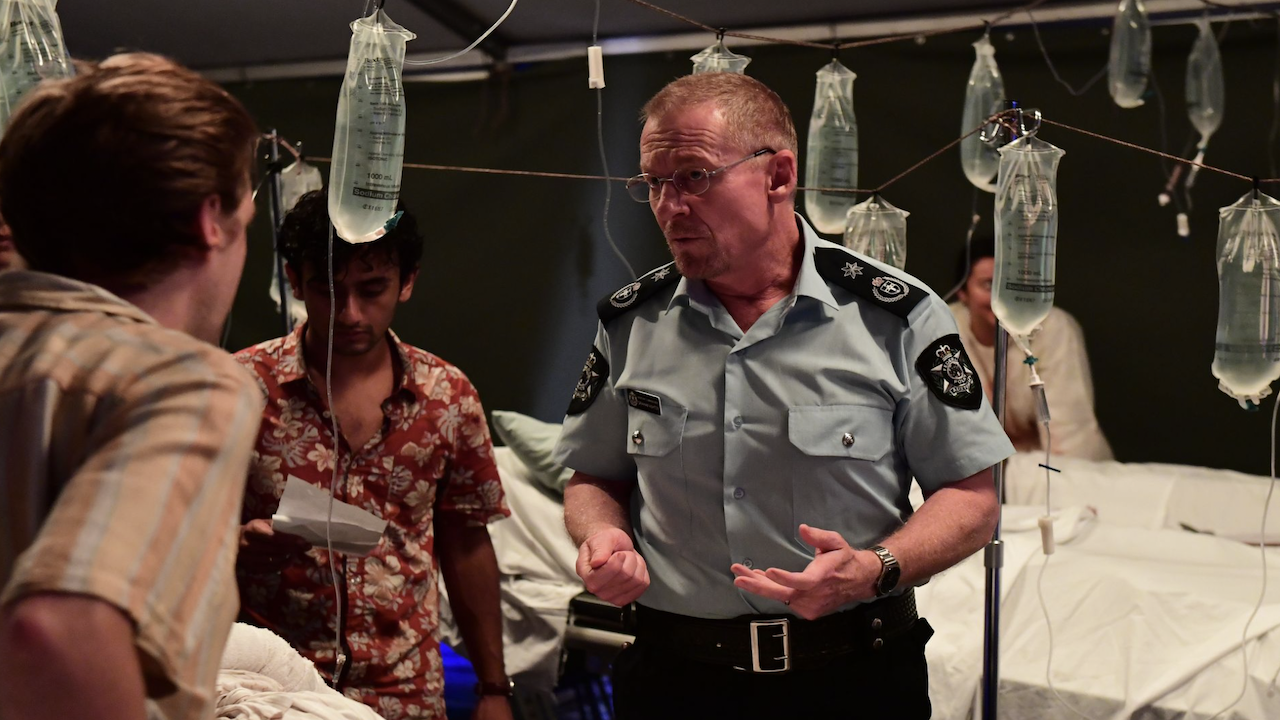

A Stan Original co-produced by Channel Nine, Bali 2002 indeed feels like an emotionally rote, made-for-TV re-enactment of tragic events that many viewers will still keenly remember unfolding on the small screen. It’s all very I Shouldn’t Be Alive, with an ensemble of beatifically smiley actors playing real tourists, and veteran Aussie screen talents Richard Roxburgh and Rachel Griffiths counted on to add some gravitas as expert authorities.

He’s the surly commander of the AFP’s investigation into the terrorist bombing, and she’s future Australian of the Year Dr Fiona Wood, insisting on the use of then-untested skin spray technology to save the lives of returned bombing victims. Like any flimsy biopic about a rock star or a genius scientist, Bali 2002 may be hindered by its respect for these real, morbid events and the heroes they forged in fire: Roxburgh and Griffiths never put a foot wrong, determinedly doing the right thing and saying all the right, placating words in a way that prestige TV storytellers would never dare to bore us with in fiction.

It’s all a bit weightless, especially once the pilot episode shows us the pivotal bombing. All Australian viewers, all Stan subscribers, will know that this moment is coming and that it’s going to change the lives of every happy-go-lucky holidayer we’ve been introduced to over the last half-hour. But that didn’t sap any tension from stories like The Impossible or Chernobyl, where one horrifying moment sends communities reeling into a future of pain and uncertainty.

And it’s significant that both those tales of explosive chaos and tragedy did not obsessively return to the scene of the crime to remind us of their impact. Bali 2002 first seems to admirably get the explosion out of the way early on in an attempt to focus on its traumatic aftermath, but then weakens the scene’s immediate drama by replaying the moment from various, increasingly irrelevant perspectives every 20 minutes or so for the remainder of the limited series. The scattered structure feels half-baked, a convenient way to explain how each new character experienced the blasts that undermines any initial momentum or suspense.

Onto that aftermath: it’s where we get the series’ best acting. As the dust clears, Roxburgh gets to deliver bitter exposition to the uncaring knobs back in Canberra (“we have a body here that has been claimed by four separate families as their son. Because it’s intact. Because the alternative’s too hard to bear.”). Sri Ayu Jati Kartika gives Bali 2002’s most grounded performance as Balinese widow Ni-Luh: her probing presence makes us question the parasitic relationship between Aussie tourism and Indonesia’s gentrification, when she sobs that “we should’ve looked after our guests”. They’re all flown home while she’s left in the rubble of “angry, confused” ghosts, unable to pay for her husband’s cremation.

That fraught, international codependency could’ve been embraced by Bali 2002 as a more compelling source of conflict than whether new amputee Nicole (Elizabeth Cullen) will get together with her hot boyfriend back in Australia, or if Roos player Jason McCartney (Sean Keenan) can make it onto a footy oval again. (The answer to both is yep, as boxy 3:4 news footage and closing title cards confirm).

Beyond the simple outrage and grief of the attack’s countless deaths, Bali 2002 could’ve crafted something more complex by honing in on these real, uncomfortable moments—where we must ask what Bali and Australia have to gain from their perhaps mutually exploitative relationship. We’re surely meant to feel provoked by clips of PM John Howard shaking his head over the tragic fallout of a “legitimate, simple overseas holiday”; the information that the bombed Sari Club would only let in “white-skinned tourists”; characters nattering about how cheap the region’s shopping is, how “gorgeous” the locals are.

But these colonial perspectives are blithely brought up and forgotten, not reaped for their potent dramatic potential. Instead the JI extremists are, perhaps understandably, singled out as the series’ sole, simplistic force of hate. They consider the murdered civilians to be less innocent than any victim of the US war on terror, tainted by “indulging in sex and parading their bodies…coming here, getting drunk, showing no respect.” Any Australian viewer, of course, will recognise these as the very tenets of our entire culture, and so will feel happily smug when Roxburgh turns the tables on their leader, revealing that he too hypocritically watches salacious Western porn.

It’s all so easy—checkmate, terrorists!—in a way that real life never is, although it does achieve the base effect of making the viewer briefly remember at least some of this real incident’s real victims. Perhaps it’s impossible or inadvisable to dramatise the Bali bombings with anything less than tearstained patriotism and grace—perhaps the island must stay an accomodating (“legitimate, simple”) holiday destination at all costs.