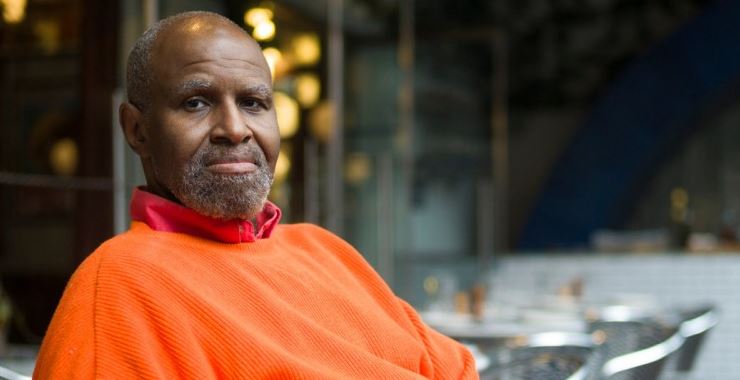

Meet Armond White, the world’s most controversial film critic

“I seriously think people don’t know what criticism is anymore, because there are so few examples of it,” the notorious American film critic Armond White tells me over the phone from his home in New York. “All they know is rating systems, and the consensus you see on aggregator websites. This has allowed a kind of herd mentality to overtake film culture. And saddest of all, perhaps, it’s not just among readers but among people who write reviews.”

White’s assessment of the current state of film criticism is damning, though that will likely come as no surprise to anybody familiar with the veteran critic’s work. How to best describe his writing to people who haven’t read him? Put it this way: remember that critically acclaimed film you recently saw and loved? Armond White (who writes for National Review and OUT Magazine) almost certainly hated it, and penned an erudite critique ripping it to shreds.

Blade Runner 2049, for example, reflects the work of an “ultra hack.” Dunkirk is “uninspiring mayhem.” Wonder Woman = “‘feminist’ in a petty, trendy way.” Manchester By the Sea is “boring and bludgeoning.” Moonlight appeals to “our most banal sympathies.” Get Out reduces “racial politics to trite horror-comedy.” It presents “contemptuous treatment of American innocence.” And on we go.

You may agree with all or none of these assessments. The point is, White is controversial. He is also perceived as an agitator for reasons other than his reviews. In 2014 White was removed from the New York Film Critics Circle after allegedly (he denies this) yelling profanities at Steve McQueen, the director of 12 Years a Slave. A few years earlier he reportedly made Annette Bening cry. Jordan Horowitz, producer of La La Land, is one of many industry figures who have lashed out at him.

Just this week, White published a tweet describing director James Toback, who has recently been accused of sexual harassment by 38 women, as the “smartest, most honest director in America.” This appears to be a form of clickbait, directing readers to a 2000 interview in which the filmmaker opened up to White about his experiences being (his words) a “wigger” or “White Negro.”

All this suggests a man comfortable with being a contrarian. I assume, also, that he is comfortable with that word. And I find out the hard way that he is not.

“I never accepted the term contrarian,” White says. “I think that’s offensive, frankly. And my response to that is: if I’m a contrarian, what are other reviewers? What I strive to do is be a good critic, not somebody who simply accepts the product put in front of me. I guess it scares people to think that they don’t have any originality; that they don’t have the capacity to think for themselves.

“There’s a line a lot of reviewers use that I don’t like at all. They say ‘accept the film on its own terms’. What that really means is, ‘accept the film as it is advertised’. That’s got nothing to do with criticism. Nothing to do with having a response as a film watcher. A thinking person has to analyse what’s on screen, not simply rubber stamp it or kowtow to marketing.”

In the age of social media, strong, outraged and outré opinions are a dime a dozen. So why do Armond White’s thoughts continue to have weight, and relevance? And why do his detractors find his presence so hard to stomach?

The answer, as I see it, relates to a couple of incontrovertible truths. One: that White is obviously (and often ferociously) highly intelligent, and highly knowledgeable about films. And two: that he is clearly a gifted writer, his scholastic critiques laced with outside-the-square statements and provocations. Extreme, perhaps. Cage rattling, sure. And interesting: always.

Take, for example, the opening paragraph of White’s critique of Star Wars: Rogue One. You may disagree with his assessment, but it is nevertheless an impressive piece of writing. Here’s how the review begins:

“My experience with watching the Star Wars franchise as an adult could be summed up during a key moment, in Return of the Jedi, that fans of the series consider a turning point in Western narrative tradition: Incredulous, I turned to a friend and commented, “I can’t believe we’re watching a puppet die.” The difference between adult and child reactions to Star Wars is central to comprehending the new installment, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, which adds to the Western economic tradition by commercializing the franchise’s fantasy appeal to post–Baby Boomer and Millennial generations.”

I’ve been reading Armond White’s work for years now, and believe I have solved the ‘riddle’ of his writing. Including why the critic rejects being labelled a contrarian, and why he so passionately rubbishes most titles that roll off the American film industry’s assembly line.

Hollywood is a famously left-leaning institution. It seems clear to me, through his writing, that White on the other hand is a hard-right political conservative, who views films as fundamentally ideologically-driven works.

So, when analysing the output of artists who generally view the world very differently to himself, and holding very passionate views, White sees every reason to bemoan; much to get upset about. Including – to cite one of many, perhaps countless examples – what he describes as “the Obama effect,” which he claims has corrupted films such as 12 Years a Slave and Django Unchained.

That attitude – viewing art through the prism of politics – might seem unreasonable when it is applied to work that does not appear, at least at first blush, to warrant it. For example, when White dedicated much of his analysis of the animated family movie The Boss Baby to the politics of Alec Baldwin, voice of the titular protagonist, who he went to town on, describing the actor as a “court jester for the angry Hilary mob.”

But it is worth asking yourself: when was the last time you watched a film or TV series that you vehemently opposed, from an ideological and political point-of-view, then went on to champion? If the answer is “never” (which it probably is) you might just have found yourself relating to Armond White.

“To me everything does have a political component and I think it’s an interesting way to look at art. It’s one way that makes film reviewing, I think, a politically relevant form of journalism,” he says. “We do live in a political world, and we bring our political sense to the movies with us – unless you’re the kind of person who goes to the movies and shuts off the outside world. I’m not that kind of person.”