The Flicks Interview Mads Brugger – ‘The Ambassador’

In The Ambassador, playing at the NZ International Film Festival, director Mads Brügger makes himself the central character in his documentary. By buying diplomatic status and exploiting it in the Central African Republic, Brügger was able to capture on film the sort of corruption that’s endemic to countries plagued by inequality and the huge sums of money that resources such as diamonds offer. Sporting dark glasses, riding boots, and a cigarette holder, Brügger claims to be a do-gooder rich businessman in the film, officially in the country to start a match factory, but unofficially he is really there to gain access to vast reserves of diamonds.

While Brügger was in town for the NZ International Film Festival, Tony Stamp sat down with him to get the lowdown for Flicks.

FLICKS: So, I guess, the big question in terms of making the film is why did you decide to put yourself into the action like that? And why did you decide to sort of play a character in the scenes?

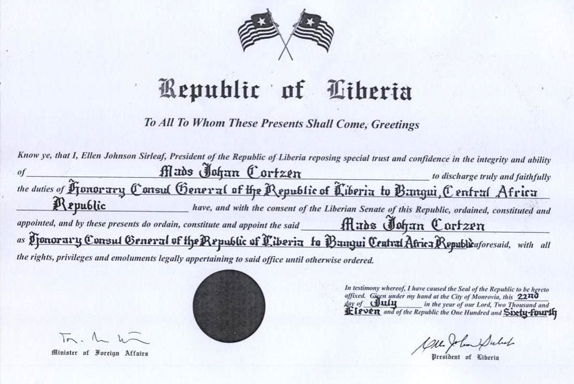

BRUGGER: Well, what really turned me on in the beginning was the idea that I could actually become a bona fide consul ambassador, you know, that would bring me beyond role playing. Because at the end of the day, whether you like the film or not, you would have to say, “Well, after all he is the General Consul of Liberia of the Central African Republic.” You can’t argue with that, which is a very unique feature of the film.

In practical terms, some critics of the film would say that the film is only about me. And I just want you to know that I am full of myself and I just want you to show off that I’m a sort of self-obsessed tourist. But, you know, in practical terms that’s the only way you can make a film like this because it would be impossible for me to direct a film standing behind the camera when making a film which is illegal and the whole process of shooting the film is secret. So, in order for me to have a feeling of how the film is coming along and what is going on within the frame, I have to be in the frame. And that’s my only possibility to affect what is going on and in the film.

it’s a film which, in many ways, also has to do with fantasies and fetishisms

Furthermore, it’s a film which, in many ways, also has to do with fantasies and fetishisms. My own fantasies about Africa but also Africans and their fantasies about, you know, white people, Western people and in some ways I am, in the film, the black fantasy of the ultimate white business diplomat because I carry myself in such a flamboyant way. A part of that, of course, has to do with survival, that in country such as the Central African Republic the only thing which is suspicious is trying to blend in.

The more you blend in the more suspicious you become. But the more you stand out, you know, the more protected you are in a sense and furthermore, the more I would engage and trigger the Africans and their fantasies about white diplomats, the more interesting I thought the action would become. And it really had an effect, you know, I promised several ministers that I would bring them the same riding boots as I am wearing in the film, and I did attract people who subscribe to the same fantasies and notions and ideas as my character subscribes to, because they could clearly recognize what kind of things I was attracted to and turned on by.

Your playing that character results in quite a bit of comedy within the film, not just in your appearance with the riding boots and the smoking paraphernalia, but also your way with a crisp one liner. Was it important for the film to be funny, or did that result unintentionally?

In Denmark, we have a thing called cultural radicalism which is an intellectual school that is quite popular in the Danish schooling system. And teachers in Denmark will tell you that is really one of the most important commandments of cultural radicalism. That whenever you say something, when you have a chance to say something funny, you should say something serious as well and vice versa. Because that will accentuate, you know, what is funny and what is serious.

Recently I read that Mugabe has been made the Tourism Ambassador of the UN. You know, if that isn’t funny I don’t know what is funny anymore

And toying with genres, I liked the idea of making an Africa documentary which also has its fun moments, because if it’s true that comedy is tragedy plus time, you know, you could argue that the only thing you have left to do regarding Africa is basically laugh, because it is so very tragic and it has been going on for such a long time. Recently I read that Mugabe has been made the Tourism Ambassador of the UN. You know, if that isn’t funny I don’t know what is funny anymore really. And having fun moments in the film really adds to bringing the audience out of their comfort zone, and I do understand if people feel bad about sitting in the theater, laughing, while watching things that are absolutely horrible, you know. But that makes the game much more interesting.

How did you go about getting such good footage? Were people ever aware that they were being filmed? And where were the cameras concealed?

Well, there is some footage in the film, which clearly is hidden camera material and these cameras we would hide, in flower bouquets and inside books and we were we were working a lot on getting good sound. You can survive bad pictures but bad sound is definitely not good. But a lot of the film has been shot on a Canon EOEO5 camera, which resembles a still camera. And in an African setting, for most Africans, it is a still camera. And I would show, when I met with ministers and people of power in the Central African Republic and Liberia, that my photographer was my Press Officer.

Everything you can attach officer to is swanky and great, you know, and they didn’t care, basically. I told them that I had hired him to document my exploits as I went about, and they just thought, well fine, who cares. So, he was able to shoot a lot of scenes which in theory would be unfilmable. Dealing with my sinister business partner, the diamond miner Monsieur Joubert, he would, again and again be telling me “what we’re talking about now is extremely secretive, if anybody finds out we will all go to jail” and he’s saying that while the camera is basically and literally right next to his face, but he didn’t care.

The way the film turns out, the tension sort of escalates and it gets very serious at the end, in terms of your jeopardy and the legality of the whole thing. Were you feeling that it was kind of turning out in your favor, because it made for a very good film narrative and also how scared were you?

I did have my moments of paranoia and anxiety, and what really helped me was having done a film in North Korea, because that made me able to deal with prolonged periods of paranoia and stress, which, you know, shooting The Ambassador certainly also involved. But I also had moments where I was enjoying myself. I know that sounds horrible and repulsive but driving through Banki in a high speed SUV together with your diamond miner business partner and your two pygmy assistants, it’s a very intoxicating feeling, and I also had moments when I thought “I’m really good at this, you know, I really know how to play the cards”.

I thought maybe this is what I should be doing for, for the rest of my life, because this is really fun

And moments when I thought “maybe this is what I should be doing for, for the rest of my life, because this is really fun”. That is, of course, craziness but we’re talking about the country where there really is no reality principle, where anything can happen at any time, and in places you’re having sundowners with the son of the president and an hour later you can find yourself in the social dungeon, not because of something you have said or done but because of something which is out of your control. I could tell you several situations where I felt this is dangerous or this is too close to the glass ceiling, but essentially once you land in the Central African Republic, once you’re on the ground, you know, everything will be dangerous and crazy.

The film strikes quite a non-judgemental tone and just kind of presents things as they are. What’s your desired reaction from the audience? What would you like them to leave the theatre thinking and asking?

Well, first of all, I don’t consider myself to be an activist. My profession is journalism. That is where I’m coming from. So I like selling it as it is, and you could also argue that, in fact, it is much worse than what I am describing in the film. Some critics of the film would say “but how come you paint this bleak picture of the Central African Republic, why not talk about something which is positive and good in the Central African Republic?” But that would really be faking it because there’s not much to be happy about in the Central African Republic

What I really liked was getting reactions from Africans that saw the film. And they told me that that they were really pleased about how naturally I was dealing with the Africans. I wasn’t treating them as somebody special or somebody that you should be careful about, or, you know, feel sorry about, which is something they are very tired of. A great many documentaries about Africa are about feeling sorry for the Africans. And they also enjoy getting to see how people of power, how they operate, you know. That is something very unique for Africans to have that experience because in many places in Africa journalists are not even able to work, you know. And the theory of journalists doing undercover work, exposing the kingpins and the wheelers and dealers of their country is beyond belief. So for many Africans this film is really an amazing experience and that is something I’m very happy about.