Happy 25th birthday Falling Down! A great film, better and edgier now than ever

In the era of Donald Trump, Brexit and other contemporary politicians and movements that reflect a time in which voter disenfranchisement in western societies has gone mainstream, in a very big way, it has become de rigueur – and also cliché – for cultural critics to proclaim certain works of art ‘perfect for the time’. But when approaching the task of revisiting director Joel Schumacher’s 1993 classic Falling Down, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary, one can hardly ignore the present political reality and pervading American sentiment. The conversation the film began when it was first released a quarter of a century ago is more relevant now than ever.

It would be foolish to suggest Schumacher and writer Ebbe Roe SMith ‘predicted’ Trump, or anything of the sort. Rather, Falling Down encapsulates – better than any film I can think of – the reasons why, and the extent to which, so many Americans (particularly of the conservative ilk) so resounding lost faith in the system, and voted to boycott the status quo in order to ‘make America great again’. The film makes ideological observations in ways that don’t speak down to either side of the political divide; nor does it retread the familiar, stock-standard narrative about evanescence of the American Dream.

Falling Down’s atmosphere is tense and street level; this vision of America throbs like a war zone. The story follows the recently divorced William Foster (Michael Douglas) who is so fed up with the system he snaps, spectacularly abandoning social mores and spearheading a range of violent confrontations. Foster’s glasses became a famous visual motif. These kinds of glasses, known as browline glasses, were popular in the 1950s. They signify the character’s political and ideological displacement; that his values emerge from a different time.

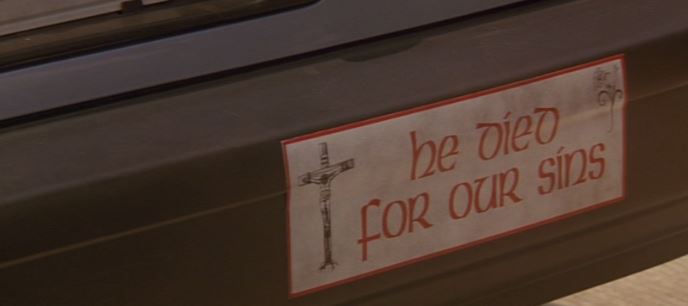

The setting is Los Angeles – presented as a microcosm of America – on a swelteringly hot day. The opening shot of Michael Douglas’ face is so close his nose consumes almost the entire frame. Schumacher eventually reveals that Foster is in a car stuck in heavy traffic. A girl stares out the back window of the car in front of him; to the right there is a school bus with an American flag draped out of one of its windows. From the POV of Foster, we see three sets of license plates, signifying different aspects of American society: capitalism, religiosity and good old fashioned American aggression. They look like this:

Schumacher cuts between a series of images of ordinary looking things – such as a plush Garfield window toy – and frames them from eerie looking angles, creating a disquieting montage reminiscent of a horror movie. The pressure in this moment builds and builds, with a suffocating intensity that represents the state of mind of the protagonist. Soon remaining in the car becomes too much for Foster, so he abandons it and commences his flipped out adventures, stomping into a range of tetchy encounters instigated by his raging demeanor.

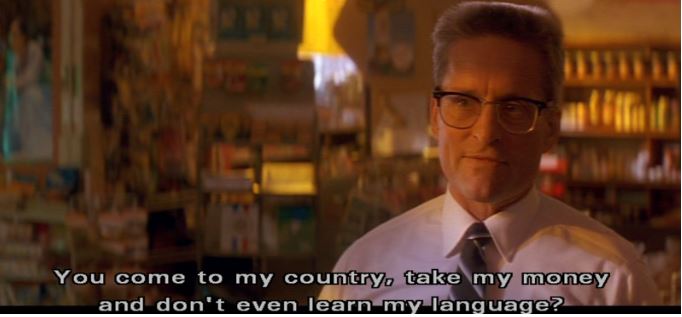

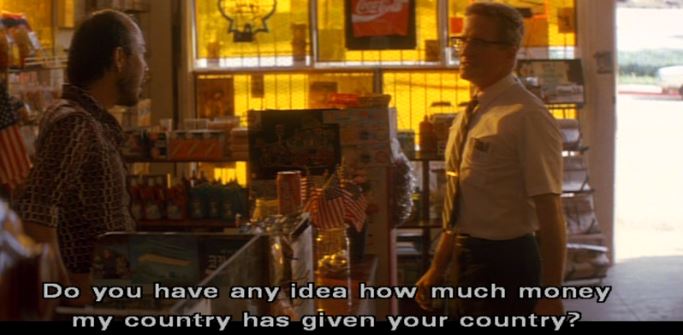

In a nearby convenience store, the protagonist requests some change so that he can make a phone call. The Korean man behind the counter demands he purchase something. Foster grudgingly accepts this but is disgusted by the price of a can of Coke, and annoyed that the man doesn’t speak fluent English. This happens:

Is this not a Trump voter sentiment, through and through? Foster ties his personal outrage to a broader grievance, considering a situation involving (supposed) international handouts to be unfair and unAmerican. He is not, however, armed with facts, and thus is thrown off guard when the Korean man responds to the above question (“Do you have any idea how much money my country has given your country?”) with the obvious counter: “How much?” Foster admits he doesn’t know, but “it must be a lot.”

The situation descends into violence, when Foster wrestles the Korean man to the ground. In the process a glass jar of miniature American flags falls off the counter and smashes. It’s a loaded image, perhaps representing commercialism at the expense of nationalism, and vice versa – or more simply, a broken system. The visual symbolism in Falling Down can be a little on the nose, but through it Schumacher and cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak reiterate a key point: this is not the story of one person but many. Foster’s individual journey reflects the attitudes of, if not a nation, then certainly a groundswell movement somewhere near the heart of it.

The film’s most memorable moments include the famous ‘I want breakfast’ scene, set in a McDonald’s-like fast food restaurant where a heavily armed Foster demands by gunpoint to be served the breakfast menu.

A more important sequence takes place in Foster’s old family home, where he used to live with his daughter and wife before she left him (and took out a restraining order against him). Here he watches old family videos on the couch, recalling memories of happier times.

This moment summarises a great deal about the conservative ethos. People who believe in conservative politics tend to, as the academic Louis Giannetti once put it, have “a deep veneration for the past,” believing society should return to a time that was fairer and steeped in ‘old fashioned values.’ They hold on to a belief that life was superior way back when, viewing the past through rose-tinted glasses. People on the left side of politics tend to be more critical of times gone by, and more hopeful for the future. They advocate social change, rather than arguing that the clock should be turned back.

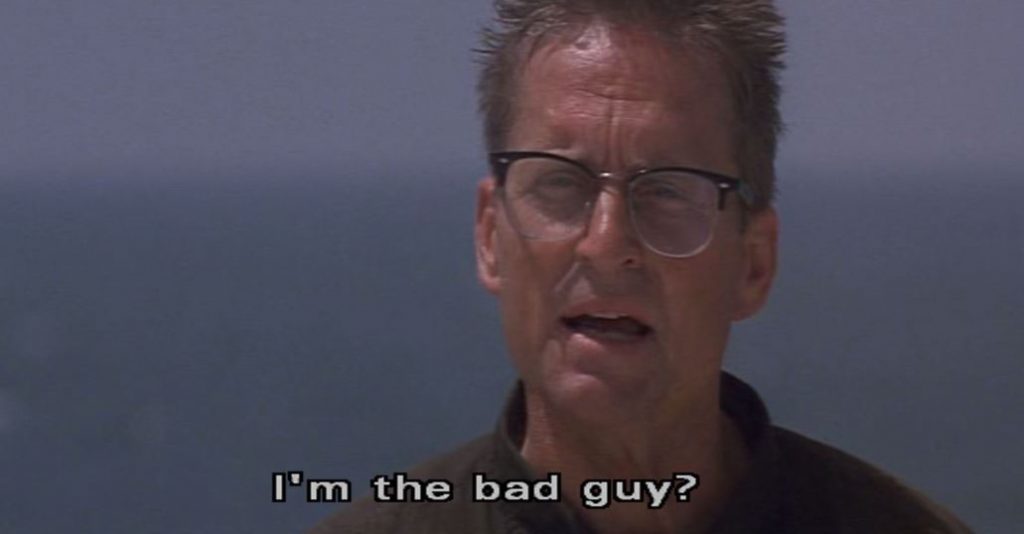

At the core of Falling Down is a deeply nuanced portrait of a bad guy. You could argue, in fact, that Foster isn’t a bad guy at all, which speaks volumes about just how nuanced the portrait is. Core to this is a sense of empathy and understanding. We relate to where Foster is coming from, and feel for him even when we do not agree with him or condone his actions. Michael Douglas’ performance brilliantly captures the complexities of this character, as well as the great sense of loss that follows him like a grey cloud, contextualising his behaviour in an overall air of melancholia.

During a final climactic confrontation involving a weary, soon-to-retire police officer played by Robert Duvall, the protagonist exclaims: “I’m the bad guy? How did that happen? I did everything they told me to.”

The greatest villains rarely think of themselves as villains. This is true in film, as in life. Almost everybody considers their own actions to be right and just, irrespective of the ‘truth’ – a concept that tends to feel black and white when we’re children and frustratingly subjective when we’re adults.

There is a lot to unpack in Falling Down; this analysis barely scratches the surface. It is a great, ideologically sophisticated film from a gun-for-hire director whose oeuvre is patchy at best, and at times downright awful (a handful of years later Schumacher directed the execrable, shamelessly shonky superhero movies Batman Forever and Batman & Robin). To say Falling Down has stood the test of time is an understatement. Twenty five years later, this squeamishly effective drama is better, richer and edgier than ever.