Retrospective: All the President’s Men is the greatest film about journalism ever made

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s investigation into the Watergate scandal is brought to the screen in all-time classic All the President’s Men. It resonates strongly watching it today, nearly five decades after it was first released, writes Daniel Rutledge.

As a journalist, films and TV shows about journalism can be especially meaningful and satisfying on a personal level. In recent years Spotlight moved me tremendously, The Post was a solid watch, and The Newsroom infuriated me with what a pile of dogshit it was.

But the greatest film ever made about journalism is 1976 classic All the President’s Men. Director Alan J Pakula and writer William Goldman’s adaptation of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s investigation into the Watergate scandal is a superb retelling of one of the most important works of journalism of the 20th century. It’s strength is in how matter-of-fact it is, packed with details and devoid of sentimentality, a respectful ode to two great men performing an incredible example of what journalism is all about: Holding the powerful to account and uncompromisingly seeking the truth, no matter how hard it is to find.

It’s now 2022 and it’s OK to not know much about what the Watergate scandal actually was, by the way. Plenty of material only a Google search away will explain it thoroughly, but in short, it was the uncovering of a bunch of crime and skulduggery committed by US President Richard Nixon’s administration. When the whole ugly truth came out, he was no longer president and nearly 50 of his cohorts were convicted.

Nixon was in power in a time when, unlike today, people would quit out of shame when they were found to be so guilty. Had he not been the only US president ever to resign—before getting a friendly pardon from his successor—he would’ve been impeached and removed from office. These days, his modern equivalents just continue to lie and deny and point fingers elsewhere no matter how blatantly guilty they are, with corrupt Senators and Congresspeople enabling them, and a brainwashed support base refusing to accept the truth.

So it’s easy to romanticise the past and All the President’s Men is very much a product of its time. It’s a glorious depiction of the way investigative journalism used to get done which may be shocking for contemporary journalists. I love the scenes inside the Washington Post’s newsroom—the constant cacophony of typewriters and old-timey telephones being dialled, rooms full of cigarette and pipe tobacco smoke—it’s a vivid depiction of what many deem to be a golden age of newspaper journalism. But it was also a time when junior journos could spend months and months on the same story, supported by a well-resourced company to do so, well before the internet came along and changed everything.

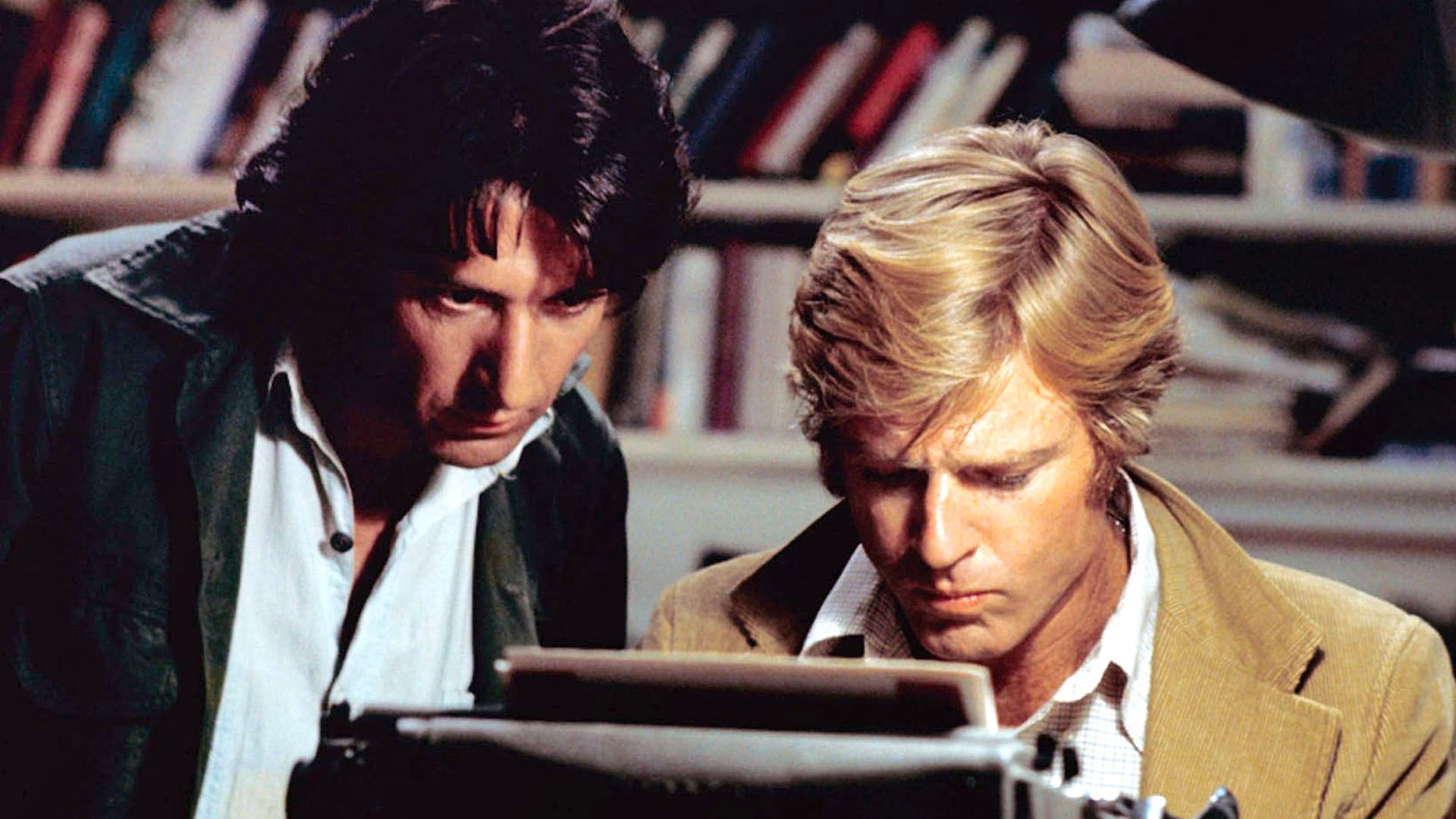

There is a distinct lack of melodrama in All the President’s Men. We see almost nothing of the personal lives of Woodward or Bernstein – there’s no romantic subplot, or any subplot for that matter. There’s only the investigation. Goldman and Pakula took a workhorse approach to this in a way that perhaps reflects Woodward and Bernstein. Likewise, the two iconic Post journos are portrayed by Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford, two of the biggest Hollywood stars of the era giving unshowy, stripped back performances and making the film all the stronger for it.

The film quietly celebrates the sheer grunt work of investigative journalism in a way that plays like a detective movie, only with no shootouts, or indeed much more than people having conversations. Yet it’s very thrilling, deftly creating a sense of horrific menace in sublimely subtle ways. As the layers of corruption are revealed, it’s impossible not to feel the thrill the characters would have felt as the puzzle pieces came together, too. The film’s final moments carry much power both because they’re perhaps the most understated of the entire running time, but they also work as a beautiful tribute to the printed word.

All the President’s Men is not just the greatest film about journalism ever made. It’s also a remarkable portrait of Americanism, for all its good and its bad. It resonates strongly watching it today, nearly five decades after it was first released, and I imagine it will continue to do so for many decades to come.