Wendy is Benh Zeitlin’s beautifully sad follow-up to Beasts of the Southern Wild

Wendy—which recently screened as the centrepiece of this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival—is a reimagining of Peter Pan, from director Benh Zeitlin. It’s frustratingly elusive but nevertheless a bold and original take on a well-known story, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

There is not necessarily all that much difference, as Benh Zeitlin’s new film hypothesizes, between appreciating youth and fearing death. The curse of age and wisdom, as most adults would recognise, is that wisdom only comes with age—and the more you age the closer you are to death. Childhood is the furthest distance, but offers the least potential for enlightenment.

When applied to the story of Peter Pan, of which Wendy is a contemporary retelling, this melancholic logic imbues the story with an extra layer of sadness. A boy who cannot age can never fully appreciate the virtues of his unique existence: blessed with youth, cursed with ignorance.

These are thoughts that swelled in my mind after the credits rolled, which ought to provide some indication of the qualities of this film: not exactly a Disney matinee shot on a soundstage with a spin-off amusement park ride in the works. It is told at every instance from an adult’s bittersweet—sometimes just bitter—perspective, with a kind of yearning very much intended for older audiences.

“Doubt yourself and you’re old already,” says Peter (Yashua Mack, a fresh-faced and striking presence) at one point. Lines from J.M. Barrie’s book can be similarly wistful (i.e. “You can have anything in life if you will sacrifice everything else for it” and “Never is an awfully long time”) but here it feels different. More an expression of the core attitude: that this film and to an extent the wider Peter Pan narrative is less about celebrating youth than fear of losing it.

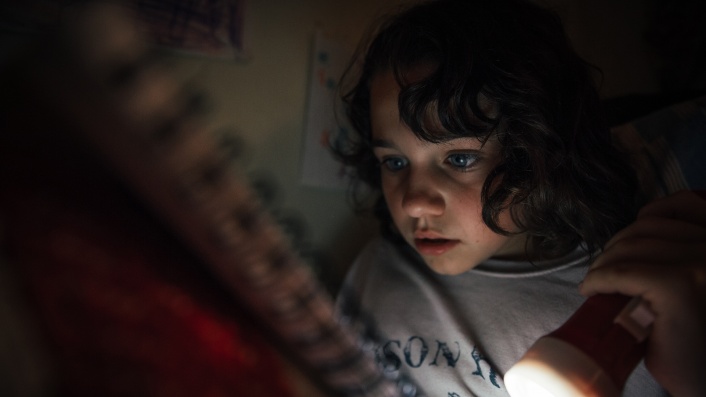

Zeitlin opens by packing in close-ups of an American diner: a jug of coffee; bacon frying on a grill; the red cheeks of a young girl. Thick streams of sunlight counter a fuzzy, handsomely unkempt texture, setting in motion a work that looks bold and beautiful in a soft way, as did Zeitlin’s rousing 2012 debut Beasts of the Southern Wild—which compared the small pleasures of being a child with the insurmountable consequences of an adult world.

Like in Beasts, the initial setting of Wendy is a kind of rural Skid Row: a Louisiana backwater, the kind of place where even dreams feel hard-earned, and which one associates with an almost innate desire to leave. And leave the kids do. Wendy (Devin France, another great and striking presence) and her twin brothers Douglas and James (Gage and Gavin Naquin, respectively), see Peter moving across the top of a freight train and join him. The train is the magical passageway connecting this world to the next—the tornado in The Wizard of Oz; the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland.

The kids arrive on an island with an active volcano, which cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen shoots with a tactile earthy texture that reminded me of Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are. Among the Lost Boys is Thomas, who disappeared from said backwater years prior, rebelling against his assumed lower class destiny by declaring he “ain’t gonna be no mop and broom man.” On the island the kids investigate a huge glowing fish, dubbed Mother, which might hold the secret to the fountain of youth. Mother is of particular interest to this version of Peter Pan’s pirates: scabby ageing men longing for a second life that belongs only in fantasy.

What begins as a exhilaratingly reimagining, cementing Zeitlin’s scruffy visual style and rough-and-tumble rhythms, becomes an increasingly drifting picture of a state of grace: a sort of sin-free Lord of the Flies, painted with the scrambled flow of partially rendered dreams. The poetic vagueness of Zeitlin’s dialogue (he co-wrote the script with his sister Eliza) has a wearying effect, as does the intangibility of the story, which I came to think of as more like a gas or a vapor than a clear trajectory forward. Narrative uncertainty is dramatically countered by adrenaline-charged production values—including a fine, uplifting score by Zeitlin and Dan Romer and the aforementioned visual boldness.

Wendy is very much a work of atmospheria, sometimes maddening but with a style, a mood, a feeling impossible to shake. The consistency of the film is debilitating; one acclimatizes to its unique qualities and then they feel unique no more. The tone is great; the lack of narrative precision hurts it. And yet I have quite a lot of affection for this film. In my mind it runs together as one long single scene, one body, stretched so far all its connective bits and faces have fallen out, the guts of it gone, leaving a beautiful empty-ish vessel. Wendy is frustratingly elusive—but vivid, memorable, and an original take on a battered text.