Special effects are more important than characters in the gloomy The House With a Clock in Its Walls

Words like “happy” and “joyous” are not synonymous with the oeuvre of director and ‘torture porn’ specialist Eli Roth, whose films (which include Hostel and The Green Inferno) feel like the work of a person dropped on their head as a child. Nor will these words apply going forward, despite Roth debuting as a director of family fare with his adaptation of author John Bellair’s popular 1973 children’s book The House With a Clock in Its Walls.

Given the film’s supposed appeal with younger audiences (though that remains to be seen, and one imagines some nervous suits at Universal right now) it is an oddly gloomy affair, with a dirgelike spirit that drains the fun from its own creations. The storyline is frustratingly vague and dialed-back performances from Jack Black and Cate Blanchett are miserably lethargic. Did Roth instruct them not to be charming?

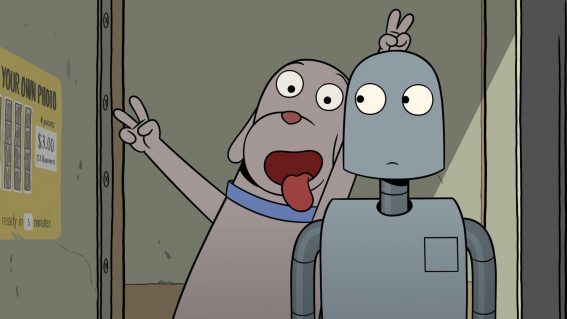

The House With a Clock in Its Walls plays like knocked-off Poe by way of Night at the Museum, capacity for wonder smothered by the business instincts of a theme park. Parentless child protagonist Lewis (Owen Vaccaro) moves into an old creaky house where Blanchett stares into thin air and Black roams the hallways at night, trying to locate a clock hidden behind the walls.

Black is the vaudevillian looking warlock Jonathan Barnavelt, who shows Lewis the ropes of (real) magic. Roth’s direction seems to consider magic also – in that he is more concerned with conjuring than creating. The house is used to activate special effects: things come out of the walls; there are phosphorescent bursts of light; a suit of armour magically awakens.

Instead of nurturing his kooky inventions the director keeps moving to the next one, with an absentminded ‘quick, look over there!’ approach channelling his inner Dory. What’s the deal with the arm chair that thinks it’s a cat? What happened to the crazy purple snake thing? Or the planetarium-like light show in the garden? Roth is reluctant to linger on anything, let alone infuse objects or events with meaning.

An under-written subplot involving Lewis struggling to fit in at school leads him to trigger the emergence of Kyle MacLachlan as a zombie boogeyman planning to end the world, which weirdly results in a Benjamin Button-esque sight gag that feels like it belongs to a different movie. At least Rogier Stoffers’ cinematography is handsomely rendered, with woody, chocolatey colour grading.

But there is very little heart in this film; very little feeling. Lewis is the ‘eccentric loner’ cipher who carries quirk with him in the form of vintage pilot goggles strapped to his forehead, as if screenwriter Eric Kripke considered outré fashion and character development to be the same thing. Every once in a while Roth switches to backstory mode, rolling out slabs of narration with accompanying grainy-looking footage styled like an old news reel.

Use of magic (which the protagonist picks up almost effortlessly) jolts the plot in different directions and creates impromptu spectacle. The characters’ actions are never as important as the special effects they create. Perhaps The House With a Clock in Its Walls will grow more enjoyable with time, when its SFX grow dated – perhaps amusingly so. Today’s cutting edge will become tomorrow’s kitsch.