Searching review: missing person thriller told entirely on computer and smartphone screens

Watching a movie told entirely from the point-of-view of computer and smartphone screens creates an odd sensation. The opening image of director Aneesh Chaganty’s missing person thriller Searching (which plays at Sydney Film Festival and will be released nationally September 13) is an exterior shot of a bright, grassy green hill beneath a glossy blue sky. Anybody who has ever operated Microsoft Windows will probably recognise this as a generic desktop background image, but you wouldn’t have seen it in this way: on a big screen at the cinema. Usually filmmakers try to avoid a stock-standard tableau; here it is the very point of the shot – to contextualise a shared visual frame of reference.

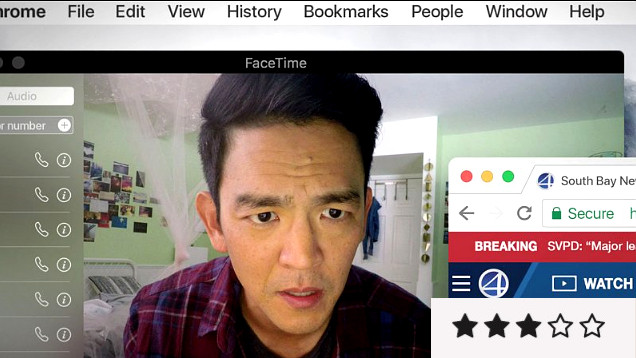

We soon see blown-up visions of Microsoft Control Panel, Internet Explorer, YouTube and various aspects of the desktop/laptop experience. We learn, with assistance from a webcam and Skype windows, that we are witnessing these interactions from the perspective of David (John Cho) and then, after a different user logs in, his wife Pam (Sara Sohn). The backstory detailed in these opening moments is nothing if not efficiently told, computer imagery presented in lieu of exposition.

A close-up of a calendar event notification (“Dr Aysola Check In”) followed by a close-up of an email subject line (“Preliminary Tests”) followed by close-up of a Google search string (“how to fight lymphoma”) imparts a clear message. Through status updates, videos, photographs, Word docs etcetera we learn that Pam’s cancer went away, then came back, then ultimately took her life, the rest of the film taking place following this prologue. Chaganty’s distinctive approach is an effective means to tell a story, though one feels reluctant to assign the filmmaker too much credit. This boxy digital aesthetic is, after all, intuitive to us all now – the opposite of visual innovation.

And yet, computer and smartphone elements used in such a way creates, at the very least, compelling visual shorthand. It signifies unconventional means to go about generating dramatic intensity and anticipation. A blinking cursor becomes an ellipsis; we wait for this half-finished moment to continue. A string of words we see typed and then deleted acknowledges a specific anxiety; perhaps even a person’s capacity for second thoughts and self-criticism.

The story that unfolds in Searching, which is a simplistic but clever multi-meaning title (searching online; searching in real-life; searching emotionally) concerns the disappearance of David’s daughter Margot (Michelle La). He starts to fret when he discovers she has been absent from school, and hasn’t been attending her extracurricular piano classes for months, secretly stashing the dosh. Did Margot nick off with friends without telling dad? Is she involved in something untoward? Is she a victim of a crime?

A determination to remain several steps ahead of the audience pushes the writers towards creative resolutions, twists and red herrings, which ironically leads them closer to a boilerplate thriller format.

The answers will be eventually revealed, after an elaborate guessing game embraced by Chaganty and Sev Ohanian’s screenplay. Keeping their narrative within the confines of a screens-within-screens aesthetic must have been a very visual, sequence-driven form of writing. A determination to remain several steps ahead of the audience pushes the writers towards creative resolutions, twists and red herrings, which ironically leads them closer to a boilerplate thriller format.

Searching is not the first of its kind. The 2015 found footage horror-thriller Unfriended, framed entirely through the lens of one person’s computer screen, introduced a rather literal take on Apple’s famous ‘spinning wheel of death’ beach ball icon. That film had a modicum of social commentary, the story spearheaded by a cyberbullying victim who returns to haunt the minds and operating systems of her tormentors. Searching doesn’t have a great deal on its mind, broadly speaking, and is perhaps most effective as an illustration of what online privacy advocates have been saying for a while: that the narratives of our lives are part of the cloud, and it wouldn’t take much for an observer to piece together the details.

Witnessing fictitious lives examined in such a real-looking format marks a curious blend of surveillance and voyeurism, with a homely, day-to-day online twist. In Searching the director neglects to address the most interesting question – of why we should care if an entire film unfolds in this way. Perhaps that question is unfair, given we don’t necessarily interrogate other films for choosing conventional visual approaches. And yet, surely, it’s the most obvious and important question of them all. Searching isn’t great, but it’s certainly interesting, with an eeriness predicated on manipulating a very prosaic and very contemporary aesthetic.