Rolling Thunder Revue is a brilliant, mind-bending film about performance and fakery

Martin Scorsese’s new Netflix documentary explores Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue tour from the 1970s. It is a terrific, strange, self-reflexive and highly ambitious electric boogaloo of a film, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

Bob Dylan has been living in the post-truth era for longer than the rest of us. The troubadour’s, shall we say, poetic attitude towards representations of himself and his art has been a recurring theme in his career since the 1960s, when legendarily combative press conferences between the prankish singer-songwriter (sometimes brandishing props) and clarity-seeking media played out like delicious farces. The artist recast journalistic inquiry into a kind of nonsense doggerel, shifting the realities in the room, creating confrontation where there was none, then turning that confrontation surreal once on board his magic swirling ship.

Martin Scorsese’s new Netflix film continues the director’s decades-long collaborations with Dylan, which began with one of the greatest concert documentaries ever made: 1978’s The Last Waltz. This new film, subtitled A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, explores the artist’s ramshackle Rolling Thunder tour, which launched in 1975. Rather than playing it as a straight history lesson, as he did in 2005’s No Direction Home, Scorsese embraces the Dylan-approved funhouse mirror approach to truth and truthfulness, engaging particularly with the idea that the act of concealing something enables unfettered honesty – or at least a liberation from inhibition.

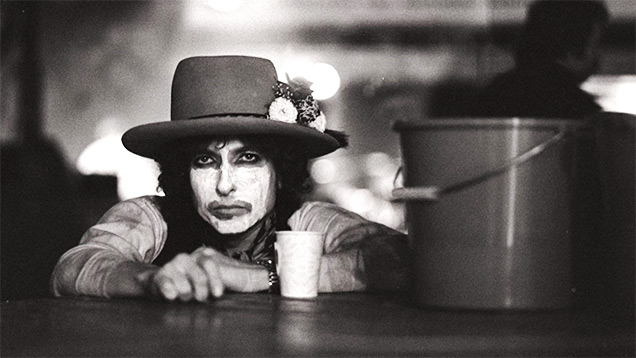

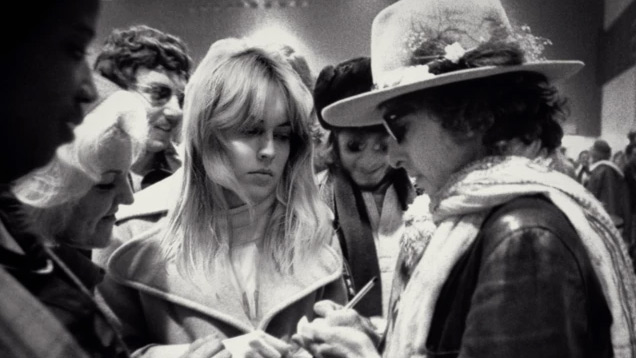

“You only tell the truth when you’re wearing a mask,” says the typically oblique Dylan, whose appearance in the film marks his first interview in a decade. Perhaps he is taking cues from his younger self, who, throughout the tour, appeared on stage beneath a flower-bedecked hat, with face smeared in eerie white makeup. Rolling Thunder Revue opens circa 1976 with grainy footage of a hustler and a street performer – buy a bicentennial hat, listen to the Star Spangled Banner! – then segues to vision of a parade and of Nixon, accompanied by Dylan crooning Mr Tambourine Man.

Scorsese cuts to the man himself in present day, reflecting on what all this touring madness really meant. The maestro’s prognosis: “it meant nothing,” he says, and in fact “happened so long ago I wasn’t even born.”

What follows is – to borrow the words of playwright Sam Shepard, who tagged along on the tour and was also interviewed – a dog and pony show. Shepard is discussing the tour itself but might as well be describing Scorsese’s ambitious electric boogaloo of a film, peppered with hot-blooded performances from a shouty and spry Dylan. In broad terms these concerts are positioned historically in the musician’s oeuvre between his spoken word poetry of the 60s and his tub-thumping Born Again period in the 80s. The film’s longer performances include near-complete renditions of Isis, Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall and One More Cup of Coffee.

Much of the running time is made up of little or never seen before tour footage, as well as footage shot for a fictitious feature Dylan was filming at the same time as touring: the critically lambasted Renaldo and Clara, which opened – and flopped – in 1978. Scorsese does not distinguish between “real” footage and scenes staged for Dylan’s movie. This is only the beginning of Rolling Thunder Revue’s – how to put it? – slippery regard for facts, or consideration of history as a potential form of pantomime.

Some present day interviewees, such as the European filmmaker Stefan Van Dorp, who reflects on the various challenges of filming Dylan and his consort, are completely invented (he is played by Argentinean performance artist Martin von Haselberg). Articles such as this can be consulted to ascertain what is “real” and what is “fake.” For the record: Sharon Stone’s account of how she attracted Dylan’s eye as a teenager, and tagged along on the tour with him, and even drew from him a claim that he wrote Just Like a Woman for her, is firmly positioned in the camp of make-believe.

But one shouldn’t overstate the film’s dishonesty, or even imply that it is necessarily dishonest in the first place. The fibs are tall tales rather than outright lies – perhaps in service of a message that being genuine and being truthful are not the same thing. Or maybe the messages is that one can be factually dishonest while still adhering to a more fundamental view of honesty. Or that every “real” legend requires a basis in reality, and that legend then hungers for fabrication the way fire reaches for oxygen – a necessary element in its proliferation.

Rolling Thunder Revue arrived on Netflix this week, around the time historical titles such as Cheronbyl and Tolkien are being probed for historical accuracy, with the general belief that fidelity to fact at least in part determines their worth. Such investigations are necessary and valuable, encouraging viewers to differentiate between various kinds of invention – those organic to day-to-day life for instance, versus those of storytellers working within structured mediums. But almost always this kind of fact-checking neglects to mention that the core challenge for filmmakers is not to recreate past events, which is impossible, but to create fiction and find ways to make it truthful.

Scorsese takes that idea and applies it to documentary, then deliberately obscures his own creations – if you can call this film entirely his own, given it is largely a work of assembly. This self-reflexiveness positions Rolling Thunder Revue alongside a string of idiosyncratic, sort-of real and sort-of not films from the last decade that have flowered in this space – among them Casey Affleck’s I’m Still Here, Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop and Kitty Green’s Casting JenBenet. These films take umbrage with Jean Luc-Godard’s famous description of the cinema as “truth twenty-four times a second,” arguing the French auteur got it around the whole way: the medium is a flickering reel of lies and distortions.

This sort of thinking is familiar ground for Dylan but new territory for Scorsese. In a sense Rolling Thunder Revue is the wily old filmmaker’s belated cinematic addition to the literary canon carved out by the Beat Generation, with hat tips to some of its biggest names – including Allan Ginsberg (who toured with Dylan and features prominently) as well as artists influenced by the Beat movement, such as Patti Smith (who appears briefly but memorably). It is for Scorsese what F For Fake was for Orson Welles: a mind-bending essay on performance and fakery. Rolling Thunder Revue even opens with George Méliès’ 1896 short The Vanishing Lady.

With Dylan in the role of the art forger, this pied piper with a jangling tambourine makes a faker out of the director too, enticing Scorsese to spin his elaborate apologia pro vita sua. This oddly exhilarating docodrama is a minor film in some ways, major in others, contrasting pure musical performance with riddles: of, as Dylan might have put it, jingle-jangle meaning and skipping reels of rhyme. Is this terrific, one-of-a-kind film post-truth? Anti-truth? Total truth? A dog and pony show? Maybe all, maybe none. It’s Dylan hiding in plain sight, dragging the concert movie medium along with him.