Joaquin Phoenix fights for nuance in the exaggerated but affecting Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far On Foot

The crowning achievement of director Gus Van Sant’s biopic of the late American cartoonist and wheelchair user John Callahan, based on his memoir of the same name, is the nuanced exploration of a tough theme: the difference between forgiving yourself and not feeling sorry for yourself. At the heart of Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot – which is essentially the story of an alcoholic’s path to redemption – is the sad belief that whenever somebody appears to have lost everything, they can always lose a little more. The silver lining according to Van Sant is that it is never too late to be kind to yourself and others.

From the very first scene, depicting a group therapy session in which several forlorn voices are heard but none of them are Callahan’s, the director struggles to identify the essence of his protagonist. The question of who this man is beyond the simplest definitions (i.e. alcoholic and paraplegic) lingers throughout. Eventually there is beauty in the synchronicity between the journey of the film and the journey of the subject: a drama that slowly comes to terms with a protagonist who is slowly coming to terms with himself.

Van Sant lurches between extremes, painting Callahan in near-caricature. We see a Hunter S. Thompson-like protagonist, in large tinted sunglasses, sweating profusely and desperate for booze while fumbling for coins and blabbering. We see him hit rock bottom, an angry paraplegic who can’t reach the bottle of demon drink he desperately craves. We see Callahan on stage recounting stories of getting wasted, which the film then visualises – each recreation playing out with the gut-sinking knowledge of the price he will ultimately pay when, three sheets to the wind, he gets in a car with the equally inebriated Dexter (Jack Black).

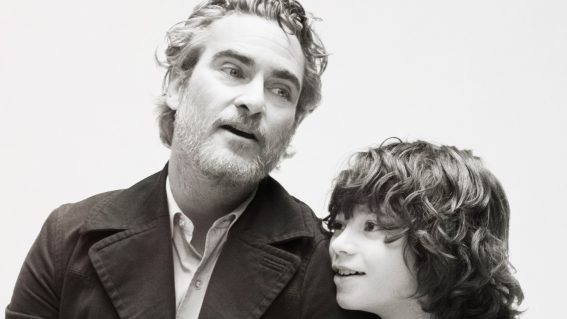

Joaquin Phoenix’s expertly controlled performance keeps providing nuance while Van Sant’s structure, which fluctuates between time frames, keeps taking it away. We know Callahan loves to drink, but why? We know he doesn’t like using a wheelchair, but who would? Why does the story for so long avoid discussing meaningful elements of its subject’s life: his upbringing, his family, his attitudes towards himself? To put it another way: why does the film for so long avoid telling us what makes him human?

An answer of sorts arrives during a scene at an AA meeting in which the protagonist ruefully reflects on his formative years and current medical condition. He explains that he was an orphaned child and bemoans the loss of his body below the chest. Instead of the group comforting him, he is attacked for singing a sad song – one woman exclaiming that “poor me poor me leads to ‘pour me a drink’.” It becomes clear the director adopted a similar hard-love stance, seemingly in the belief that compassionately reflecting on Callahan’s past might risk making excuses for his booze-addled present.

The trade off hardly seems fair – too little compassion for fear of too much sentiment – but at least the film comes from a place of deep consideration. And at least it has Phoenix’s performance to nudge it towards sophistication, as well as the softly explorative cinematography of Christopher Blauvelt, which feels like it is evolving and metastasizing. Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot is sprinkled with short animated illustrations of Callahan’s drawings, but it’s easy to forget you’re watching a film about a celebrated cartoonist. Like the recent Australian film Acute Misfortune, it never puts the art above the artist.