Belfast’s love-letter to childhood is sweet – some might say syrupy

Kenneth Branagh is accumulating Oscar buzz with his semi-autobiographical childhood drama set in the Northern Ireland capital during the late 1960s. As Matt Glasby writes, as a coming-of-age story Belfast is sincere and well-made, if unsubtle.

Time was, Sir Kenneth Branagh was the boy wonder of the British film industry, a “new Olivier” directing and starring in the Shakespeare adaptation Henry V (1989) among many, many others.

But middle-age has softened the Kennergiser’s vaulting ambition, and he seems to have settled into his niche, directing respectable blockbusters such as Thor (2011), Cinderella (2015) and Murder on the Orient Express (2017), while bringing gravitas to the likes of Dunkirk (2017) and Tenet (2020).

In a dramatic change of pace, Belfast takes its cues from Alfonso Cuaron’s intimate, award-winner Roma. Shot in beautiful black and white by Branagh’s regular cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos, it’s a fictionalised version of Sir Ken’s 1960s childhood amid the Northern Irish Troubles. As well as directing, Branagh wrote the screenplay, only the second original script of his career.

Beginning with bright, saturated-colour shots of modern Belfast, the camera moves over a graffitied wall into black and white. It’s an elegant transition that marks a shift not just into the past, but into idealisation, something the film will grapple with throughout.

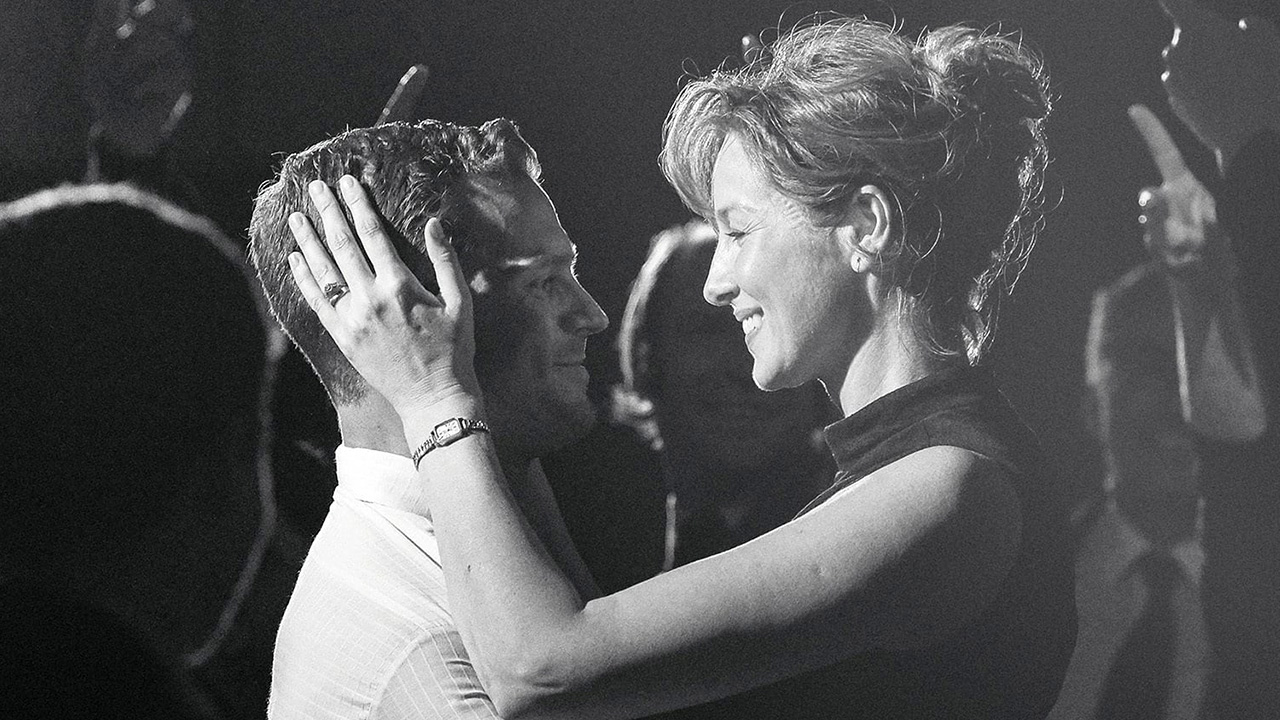

Immediately, a riot begins. The Protestants are trying to scare the local Catholics out, and barricades are erected at each end of the street to keep the peace. We then meet the film’s protagonists: nine-year-old Branagh stand-in Buddy (Jude Hill), his brother Will (Lewis McAskie), their Ma (Catriona Balfe) and Pa (Jamie Dornan), plus Granny (Dame Judi Dench) and Pop (Ciarán Hinds).

Pa’s working abroad in England, and wants the family to move with him; Ma’s worried about the bills; Will’s being asked to deliver messages for local agitator Billy Clanton (Colin Morgan); and Buddy’s trying to make sense of it all. Along the way, we’re shown Buddy reading The Mighty Thor and Agatha Christie—essentially call-backs to Branagh’s own career.

It’s an excellent cast. Hill is appropriately apple-cheeked; Balfe (perhaps the film’s standout performer) and Dornan make a convincing—if improbably good-looking—couple; and Hinds and Dench are twinkly charisma personified. For the record, Dame Judi has earned the right to speak in whatever accent she wishes. And she does.

There are funny moments too. After Pa calls Catholicism the “religion of fear”, we cut to a Protestant minister (Turlough Convery) proclaiming, “Protestants! You! Will! Die!”. Elsewhere, Buddy’s attempts at shop-lifting keep ending in disaster. The first time, he grabs a Turkish Delight, even though nobody likes them. Next, while the shop is being looted, he takes some washing powder. “It’s biological!” he tells Ma, as if that excuses his behaviour.

Sir Ken has never been one for subtlety, and there’s little in evidence here. We cut from Clantan’s threats to a roiling volcano on the cinema screen courtesy of One Million Years B.C. Later, Buddy tells Pops there’s only one right answer when it comes to maths. “If that were true people wouldn’t be blowing themselves up all over this town,” comes the trailer-friendly response.

As a coming-of-age story, Belfast is sweet—some might say syrupy—and sometimes it’s hard to tell if the events seem simplified because we’re seeing them through Buddy’s eyes, or simplistic because we’re seeing them through Sir Ken’s.

But then this isn’t really an attempt to make a Shane Meadows film or social history, it’s a sincere and well-made love letter to childhood and cinema: a portrait of the artist as a (very) young man.