Why Unbreakable is one of the greatest superhero movies ever made

The trailer for director M. Night Shyamalan’s next film Glass has recently been released, revealing Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson reprising their roles from the 2000 film Unbreakable. Now almost 20 years old, critic Luke Buckmaster revisits Unbreakable and argues that it is one of greatest superhero movies ever made.

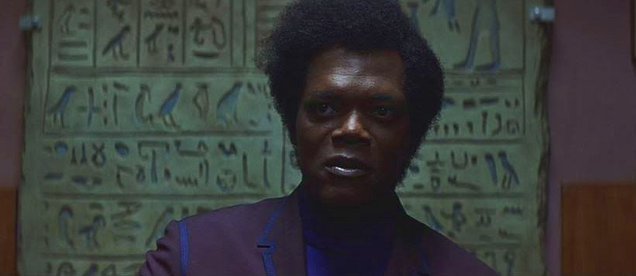

In director M. Night Shyamalan’s fourth feature film, the superhero movie Unbreakable, comic book collector Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson) puts forward a convincing argument that his beloved art form is comparable to work produced by the ancient Egyptians. Expanding on ideas famously unpacked by Joseph Campbell, about the cyclical nature of storytelling and its deep roots in human experience, Price, seated in front a wall of hieroglyphics, describes comics as “our last link to an ancient way of passing on history.”

More then that, he sees them as an answer to the riddle of his own existence. Born with osteogenesis imperfecta (also known as brittle bone disease) Price wonders whether there might be someone on the opposite end of the spectrum who doesn’t get sick and doesn’t get hurt: “The kind of person these stories are about. A person put here to protect the rest of us.”

Like the recent indie drama Columbus, which follows two melancholic characters with complicated attitudes towards building design and asks whether architecture has the power to heal them, Unbreakable deals with the assumptions we have about a ubiquitous art form and challenges us to think again. Shyamalan made not just one of the better superhero movies, but one of the best. It’s a film that stands up beautifully almost two decades later, because it is rooted in the principles of interesting cinematic storytelling.

When Unbreakable arrived in 2000, the superhero genre wasn’t the market-saturating force it is today: the contemporary equivalent of the western, with new additions seemingly arriving every other week. Price even had something to say – which proved prophetic if applied to superhero movies – about how the exquisiteness of comics risked being “chewed up in the commercial machine,” with big corporations pumping out “titillating cartoons for the sale rack.”

Critic Stephen Metcalf, in a recent essay for The New Yorker, examined the evolution of superhero movies succinctly if simplistically, observing that “when movies were mostly one-offs – and not spin-offs, sequels, reboots or remakes – they had to be good.” Because “conjuring a universe out of nothing, bringing it to crisis and back again, all in under two hours, required, if nothing else, craftsmanship on a level admired even by European snobs.”

And most interestingly: “The benchmark for a good movie was once coherence, and this meant more than a competently executed three-act script. It meant the unity of story with character.”

Unbreakable is one of the genre’s best examples of this unity. The film begins with intense mystery, as a doctor arrives to inspect a newborn baby and is shocked by what he sees. The doctor ruefully explains to the mother that the infant (a very young Elijah Price) emerged from her womb with broken arms and legs.

There are other stand-out moments that similarly imbue far-out situations with hugely affecting human details and conclude with an ellipsis, creating a strong desire to know more. In one of them Dunn is in a hospital room. The doctor informs him that the train he was travelling on experienced a horrific accident, crashing and killing everybody on board other than him. This establishes the first steps towards David’s realisation that he has super powers. The camera captures the moment several metres away, as if hesitant to get too personal with the protagonist too quickly.

Similarly, when we meet Dunn on the train in an earlier sequence, he is observed from between gaps in the seats in front, which obscure our view. Later, during an intense conversation between the protagonist and his wife, played by Robin Wright (their marriage is on the rocks) the camera begins well away and slowly moves into their space.

Cinematographer Eduardo Serra’s camerawork is always interesting and at times enthralling. Unlike most superhero movies of late, his compositions are given space to breathe rather than smashed to pieces in the editing room. One scene, depicting a formative moment in which a young Price is counselled by his mother about fear, comprises a single unbroken image (lasting for almost two minutes) captured in the reflection of an old television set.

Most memorably, Unbreakable is a film about purpose. Not just finding a purpose in life but considering what that purpose might mean in the scheme of things. In the rousing final scene (spoilers will follow) it is revealed that Price is the villain. He orchestrated terrible things, including the train crash, to find and test the hero – an elaborate way to smoke out that person on the opposite end of the spectrum.

Price has used comic book stories as a way to justify his own existence. Acknowledging that he is the bad guy, he half shouts and half sobs: “Now you know who you are, I know who I am. I am not a mistake!”

This is where the film revels in a quasi-spiritual ideology about heroes and villains. Shyamalan proposes a moral equilibrium balanced by extremes (good and bad, like the Force in Star Wars) with most of life existing somewhere in the middle. Is Price a bad man or does he just understand his place?

He is a pea in the same pod as the singing and dancing, tomato red cartoon Lucifer who arrived one year before in the 1999 comedy-musical South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut. Writer/directors Trey Parker and Matt Stone extracted comic mileage from the idea that Satan might actually be a swell guy, comforted by the belief that without darkness there would be no light. The filmmakers may have been having a laugh when he sang “without evil there would be no good so it must be good to be evil sometimes,” but they inadvertently touched on something profound.

In Unbreakable there is no “inadvertently” about it. This excellent and highly distinctive film is, and always intended to be, profound. Its seriousness never feels pretentious, and Shyamalan manages to have his cake and eat it too – deeply considering the essence of the superhero genre while delivering all the spoils of it.