The Whale is getting harpooned by critics — so we review 14 wildly wrong reviews

Picking apart some of the most confusing criticisms of divisive drama The Whale, Luke Buckmaster defends Darren Aronofsky’s moving and complex work.

The Whale (2022)

I was profoundly moved by Darren Aronofsky’s new film The Whale—an intensely thoughtful and humane character study that has, as you might know by now, a stirring performance from Brendan Fraser at its core. Despite being caked in prosthetics and buried underneath a fat suit, it’s obvious that Fraser’s acting is exceptional; you can tell that just by voice and eyes. He has this way of looking at you—or through you—that oozes sympathy and hurt. In quiet, understated ways, Fraser’s character Charlie—an online college tutor who rarely leaves his apartment—calls for a world with more empathy.

Films have a long history of crude representations of obese people, which is partly why using fat suits has become a source of contention. But it’s crazy to suggest Charlie is a one-dimensional character. Even the film’s detractors don’t usually go there, tending to focus instead on Aronofsky’s direction and aspects of the writing (which I’ll get to in a moment).

Adapted by Samuel D. Hunter from his semi-autobiographical play of the same name, the protagonist is a complex individual full of contradictions: strong, fragile, bold, pathetic, gentle, hardhearted. One important fact missing from much of the discourse surrounding the film is that he has an eating disorder. Which—like many disorders in real-life—was triggered by a traumatic incident: the suicide of his partner.

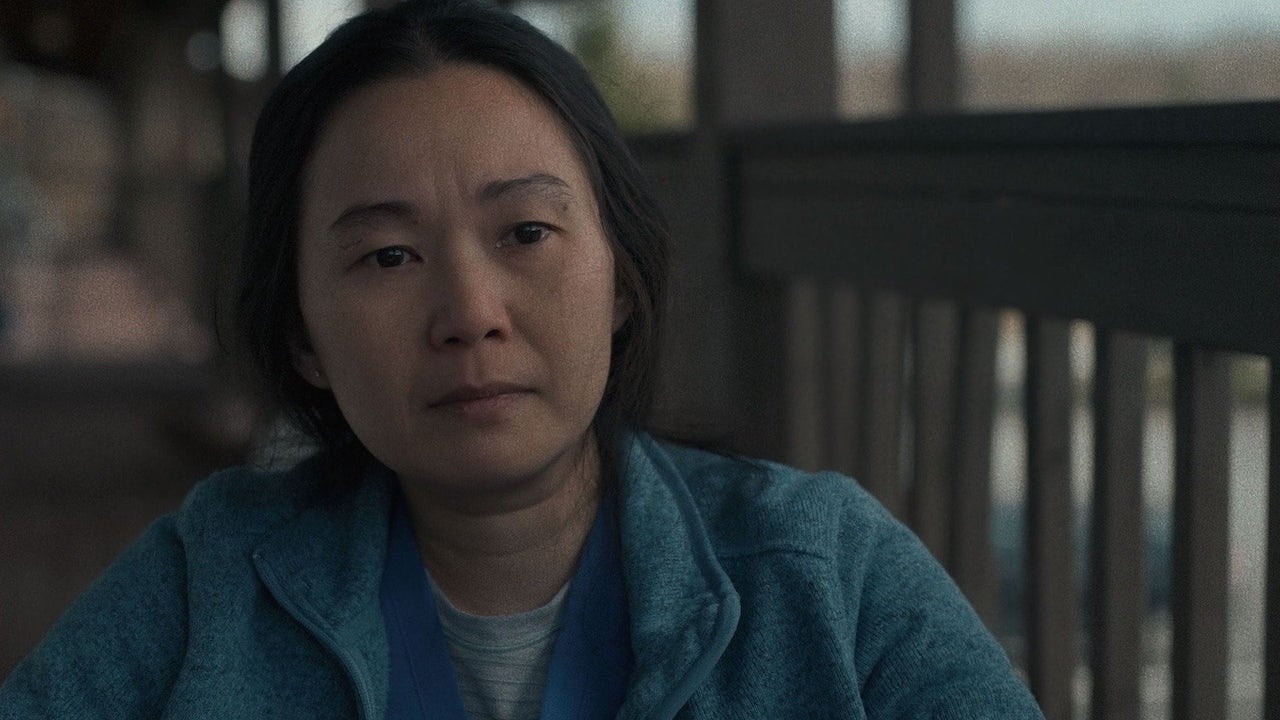

We meet Charlie as he jerks off to porn then has a heart attack—and things don’t get better for him as the runtime progresses. He’s told in no unclear terms that if he doesn’t seek help, or turn his life around, he will soon die. A couple of people want to help: namely his best friend Liz (Hong Chau) and a young missionary, Thomas (Ty Simpkins), who sees his sickness as an opportunity for conversion. But one can sense early on that this is a tragedy, which is no surprise in the context of Aronofsky’s work (his oeuvre includes Requiem for a Dream, The Wrestler, mother! and Black Swan). Plot-wise this near-single setting production is the director’s simplest film; thematically it’s one of his richest—rivaled only by The Wrestler, another film intensely connected to the physicality of its protagonist.

One can spend a lot of time in Aronofsky’s films waiting for the declaration of an obvious, palatable sentiment: that moment when he holds the viewer’s hand and finally reveals the picture’s moral centre. Almost always this never arrives, leaving viewers—including and especially critics—flummoxed and rattled. There’s something about his style that pushes the blood to our heads and gets people responding passionately, even hysterically. And yet, understanding all of this, I was still dumbfounded by negative reviews of The Whale that I found to be weird, wrong, and problematic.

Interpreting films from different points of view, and exchanging clashing opinions, is one of the great features of this—or any—art form. But for me, many reviews of The Whale went beyond the pale: missing the point, misinterpreting the film, and making spurious or simply untrue observations. Before I continue this conversation: below are more than a dozen examples, including quotes from the review followed by my thoughts, conferred in the spirit of robust discussion that Aronofsky has a way of bringing on. Afterwards, we’ll debrief. Take a deep breath. Let’s begin.

Sean Collier, Pittsburgh Magazine:

“It (Charlie’s optimism) gets to the heart of the story, that a downtrodden man with plenty of reason to become embittered can, even at the brink of oblivion, find beauty and wonder in the world.”

That’s not the heart of the story. The heart of the story concerns a person who, at the brink of oblivion, unwilling or unable to help himself, looks back on his life and is determined to assign it one true, meritorious purpose. The tragedy of this is that the person who Charlie believes gives his life value—his cruel teenage daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink)—may be unworthy of his kindness. It’s important to make this distinction (rather than mistake the message for being about finding beauty and wonder) because it adds an additional tragic layer to the narrative.

Chris Fell, The Daily Beast:

“The film would rather make Charlie a divine saint, willingly accepting his daughter’s constant epithets and speaking like a motivational cat poster.”

Divine saint?! Observations like this (including the description “Christ-like”) appear in several reviews. All of them unfounded. Charlie is an optimist but he’s also deeply flawed. He lies to his best friend, for instance, acts intemperately to his students, and must be held at least partly responsible for the disintegration of his relationship with his ex-wife and daughter. Charlie is no saint. And the reason he says lines like “she’s amazing!” to describe his daughter (I assume this inspired the “motivational cat poster” comment) is stated in my previous response: he desperately wants to believe she’s a good person. Also, he doesn’t know her well.

Eileen G’Sell, Detroit Metro Times:

“Did he have to be 600 pounds? Fraser is already a large actor and would arguably be even more vulnerable onscreen as a very overweight man, rather than a morbidly obese one.”

There’s a valid conversation to be had about the ethics of actors wearing fat suits. But the idea that the film could be improved by slimming down the protagonist would risk derailing the narrative logic on which the entire experience is based. It’s essential that Charlie is at death’s door: so unhealthy, so obese and immobile, with such dangerously high blood pressure, he might drop dead at any moment. Making him thinner or healthier would risk shattering the narrative’s plausibility.

Odie Henderson, Boston Globe:

“The disdain starts from the opening scene…Watch how this scene is edited, how your eye is forcibly drawn to the gay porn on Charlie’s laptop screen.”

Forcibly drawn? The critic seems to be suggesting that Aronofsky cuts to a full screen image of men fornicating, or something comparable, dictating our gaze and visual point of interest. This doesn’t happen. The above comment says more about the nature of porn (it’s like the sun: you can’t help but look) than any decision made by the filmmaker.

Brian Formo, Collider:

“The characters in The Whale only speak direct wants, needs, and desires every moment they are on screen. It does not feel organic or real.”

This happens quite a lot: a reviewer dilutes their criticism by stretching it to the point where it’s factually incorrect. The characters do not express “wants, needs, and desires every moment they are on screen.” There are too many examples disproving this to list. Here’s one: when Charlie talks to his class about writing persuasively, telling them to “think about the truth of your argument” and reminding them that “the point of this course is to learn how to write clearly and persuasively.”

Eileen G’Sell, Detroit Metro Times:

“What is most sad about this movie…is that none of the people onscreen—no matter their size—bear the complexity of any one of Melville’s minor characters.”

The critic is referring to minor characters in Herman Melville’s great novel Moby-Dick. This is a peculiar comment to make, given the title of The Whale refers to an essay written about Moby-Dick, not circumstances inside its narrative world. But, moving on, the statement isn’t true. Is the critic seriously suggesting that no-one in The Whale—including Charlie—is as complex as the landlord character, introduced in chapter three of Moby-Dick? Melville uses this character primarily to further the plot (he allows Ishmael, the protagonist, to share a bed with a harpooner) and divulge information about other characters (for instance he explains that the harpooner has embalmed human heads from New Zealand). Charlie, Liz and Thomas are all far more complex characters than the landlord!

Richard Lawson, Vanity Fair:

“When we do feel some of the innate sweetness that has always animated Fraser’s work…it’s usually because he’s acting opposite Chau, whose performance is the only thoughtfully calibrated thing in the film. Fraser and his other co-stars only threaten to tear down the delicate space that Chau creates and then must rebuild, scene after scene, throughout the movie.”

Hang on a moment: this is Hong Chau’s movie, not Brendan Fraser’s? Fraser’s sensitive, sophisticated, justifiably acclaimed performance gets in the way? I agree that Chau delivers a strong and moving performance. But to suggest that Fraser’s performance was not thoughtful, and in fact destroys the delicate space Chau recreates, forcing her to rebuild scene after scene, is…certainly a unique perspective. Needless to say, Charlie is the heart of the soul of the film.

Rich Juzwiak, Jezebel:

“…Charlie’s size hides greater pain deep down—he points out to Liz that his internal organs are ‘two feet in, at least’—which is yet another predictable observation about fatness.”

The above quote belongs to a dark joke delivered from Charlie to Liz. For full context, she says: “You say you’re sorry one more time, I will shove a knife into you. I swear to God!” And he responds: “Go ahead. What’s it going to do? My internal organs are two feet in at least.” It’s a bleak, unexpected, self-effacing joke. It’s not an observation, let alone a predictable one.

Anne Hornaday, Washington Post:

“…the too-pat dialogue, combined with an orgiastic rock-bottom scene, finally undercuts whatever authentic feeling Fraser succeeded in building up, a sense of falsity that culminates in a literalistic misfire of a final image.”

I won’t spoil the final images. Suffice to say they’re symbolic, not literalistic.

Keith Phipps and Scott Tobias, The Reveal:

“When Aronofsky’s camera settles in on Charlie, the 600-pound hero of The Whale, he conjures the most repulsive introduction imaginable: a sweaty, wheezing shut-in masturbating to internet porn and giving himself a heart attack at climax.”

My first inkling was to respond to this by listing a series of things far more repulsive than a fat man masturbating to porn then having a heart attack. Of which there are many. Countless. Surely these critics are familiar with horror movies that contain brutal, bloody gore and murder. Aren’t these things more repulsive than masturbation and a heart attack?

David Sexton, New Statesman:

“It’s thought that 42 per cent of American adults are obese, and 18 per cent severely so. The reasons, it is suggested, are complex and multi-factorial. Darren Aronofsky’s film The Whale offers a simpler explanation: here obesity is presented as an individual tragedy, a response to intolerable unhappiness.”

Firstly, instead of prefacing a statistic with words that undercut their validity (“it’s thought that…”) it’s best to cite credible statistics and studies. Refer to the experts. Secondly, “intolerable unhappiness” is not a synonym for “trauma.” The film clearly explains that Charlie’s eating disorder began after the trauma of his partner dying. There are many peer-reviewed studies identifying the connection between trauma and eating disorders. Here are several.

Katie Rife, Polygon:

“Charlie’s nurse and only friend, Liz (Hong Chau), is mostly kind to him, although she enables him with meatball subs and buckets of fried chicken.”

I don’t mean to sound like a stickler, but providing fast food to a fat person is not enabling them. Is the critic suggesting that a responsible friend would only bring Charlie salads and fresh juices? Just as you can’t force a drug addict to stop taking drugs, you cannot force a person with an eating disorder to eat well or exercise. Liz understands that Charlie’s one great comfort in life is food. She always understands she can’t force him to change. “Enabling” isn’t the right language.

Dominic Griffin, Baltimore Beat:

“…as any cursory glance at photos from any of the play’s real-life productions will show—each image resembles a still frame from a Farrelly brothers comedy; the source material has a deluded and pompous sense of self-righteousness to mask its ugliness.”

Every image of the play resembles a Farrelly brothers comedy? Really?! You can find examples of photos from the play here, here and here. None of those examples look like stills from a Farrelly brothers comedy. Also why is the critic analysing stills from the play in the first place?

Christy Lemire, RobertEbert.com:

“The difference between those films (Aronofsky’s previous work) and The Whale is their intent, whether it’s the splendor of their artistry or the thrill of their provocation. There’s a verve to those movies, an unpredictability, an undeniable daring, and a virtuoso style. They feature images you’ve likely never seen before or since, but they’ll undoubtedly stay with you afterward.”

I understand the spirit of the criticism—that Aronofsky’s other films are visually bolder and more striking—but it confuses style with ideology. Or at least uncomfortably combines stylistic intent with moral interpretation. There’s an inference that a more virtuoso style equals a better or even more principled film. I doubt The Whale could have been improved by bold, daring, unpredictable, skittish cinematography and editing. The restrained visual style helps keep the viewer’s attention focused on Charlie and the supporting characters. Showing visual restraint is often considered a virtue.

**

So, what can be learned from the above exercise? Firstly, my responses were not intended to discredit the critics: everybody (including myself) makes mistakes in their writing and interpretations from time to time. Most intriguing was how many reviewers made erroneous and/or problematic comments. When I started reading positive critiques of The Whale, it became apparent the only point of consensus (more or less) was the quality of Fraser’s performance. Interpretations about its ethics were wildly antithetical: where some saw cruelty and exploitation, others (like myself) saw tenderness and humanity.

These wildly different responses can be put down to the viewer’s moral compass being thrown out of whack by the movie. As I previously mentioned, Aronofsky doesn’t hold our hand and reveal clear a moral perspective, as much as we may want him to. There’s also the issue of the fat suit, which was surprisingly under-played in many negative critiques (not to be confused with think pieces and news stories). I’ve read a lot of critiques of The Whale—and it’s clear there’s no consensus among critics about the ethics of wearing them. Will there be a clear ethical consensus in 10 or 20 years time? It’ll be fascinating to find out. Perhaps we can return to the film then. It will remain the same, frozen in time, while the discussion rages on.