The visual inventions of The Irishman, from tracking shots to deadly callbacks

It’s easy to forget how visually impressive Martin Scorsese’s new gangster epic is, writes critic Luke Buckmaster, because the film is so impressive across the board.

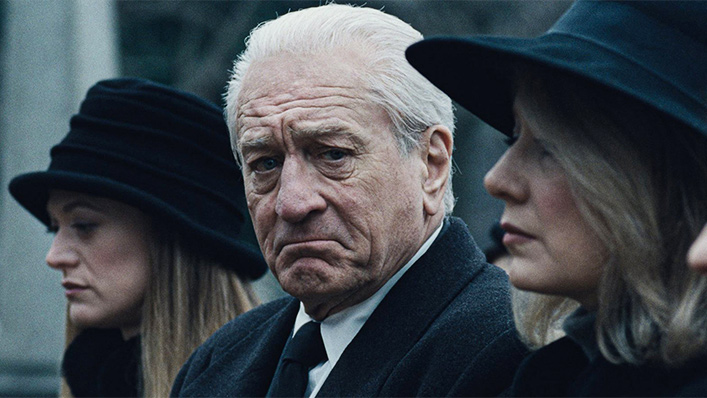

Lengthy tracking shots, vintage R&B and doo-wop, extensive voice-over narration, sudden bursts of violence, a sprawling rise-and-fall narrative, Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci as made men with axes to grind and scores to settle: ah, Marty, great to have you back doing your gangster thang. There’s nothing quite like watching a Scorsese crime movie, as I was reminded during a recent trip to the cinema – to see the very long and very impressive Netflix-bound epic The Irishman, set in one of the legendary auteur’s favourite places: an institutionally corrupted postwar America.

Listening to DeNiro address the camera during the opening reels, presenting the audience a narrative offer we can’t refuse, felt almost like returning to a cinematic home away from home. To a place where – to borrow the parlance of this film and the book on which it is based – they paint houses. The painting of said homes not exactly involving a tin of Dulux and a roller. The “paint” is more a “spray.” And the colour of the spray, if you catch my drift, is inevitably blood red.

Scorsese frames the perspective of The Irishman – both the film and, in a sense, DeNiro’s character Frank – from just to the side of major historical events. We see news flashes of Castro and are very much aware that infamous union boss Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino) despises JFK, barely hiding his glee when he learns of the President’s assassination while consuming an ice cream sundae. Discussions posed in this film, as in The Godfather, probe at the immigrant experience, the nature of modern dynasties and whether politics is a form of mobsterism – and vice versa.

With this kind of dramatic heft, coupled with the veteran auteur’s fire-on-all-cylinders approach – acting, dialogue, narration, music etcetera coming together like a thunderclap – it is easy to forget how visually interesting Scorsese is. With that in mind, let’s take a look at some of The Irishman‘s most interesting visual elements.

De-ageing technology

Everybody’s talking about this, which isn’t necessarily a good thing; it’s dominated the conversation. As the protagonist delivers his opening spiel, Scorsese cuts from a feeble and very old-looking DeNiro to a substantially younger CGI-swathed incarnation, winding the clock back several decades. As soon as the de-aged DeNiro appears, behind the wheel of a green food truck, you can spot something funny: a peculiarity in his facial features, which look blurrier and more plastic-like than they ought to.

Over the course of the film’s – shall we say – ample running time (it clocks in at 209 minutes) I puzzled over what exactly the director and his VFX team got wrong. Too little detail? Too much detail? Not enough attention to DeNiro’s eyes? Too much attention to his eyes? I came up stumps, ultimately – reverting to a basic uncanny valley prognosis: that DeNiro’s face appeared sort of real and sort of not.

I liked the film so much I found myself making up all sorts of creative justifications. The de-ageing effects enabled the veteran actor to reference his own career, I told myself – DeNiro’s computer-enhanced presence comprising one living, breathing, time-cheating homage to himself. I was grasping at straws. The de-ageing CGI is distracting. Thankfully the film’s many strengths overpower it.

Tracking shots

Scorsese opens The Irishman by moving the frame forward through a nursing home, capturing old-timers as they play cards, put together a jigsaw and socialise, before arriving in DeNiro’s lap. This shot is matched to a needle drop: film industry slang for making a piece of music a prominent part of a sequence. In this instance it’s The Five Satins’ In the Still of the Night, which the director returns to several times as an audio callback.

The tracking-shot-needle-drop is a nifty trick – and not the first time Scorsese has used it. In Goodfellas his camera famously ventured through New York’s Copacabana nightclub in the “Copa shot,” not unjustly described by Filmmaker Magazine as “one of the few shots in the history of cinema readily identifiable by name.” It’s an unbroken image needle dropped to the tune of The Crystals’ Then He Kissed Me.

Death declarations and callbacks

The Irishman introduces a range of slippery nogoodniks, many of whom fret their hour upon the mafia-managed stage then are heard no more. For some of these characters, the first occasion we see them is matched to a freeze-frame visual explanation of the last moments in their lives, the cause of their deaths explained through text overlay. This is another visual flourish that never gets old.

We are told for instance that one goon will be “blown up by a nail bomb under his porch.” Another will be “shot three times in an alley.” And another “shot eight times in the head in a Chicago parking lot.” We come to expect these summations and enjoy the grim familiarity of their repetition, forcing us to consider the narrative from a distanced perspective.

Scorsese deploys visual callbacks elsewhere, including shots that sound blandly simple when you describe them but are actually quite thrilling to watch – including images capturing the contents of a car boot and aerial perspectives of vehicles navigating a particular suburban street corner during the final act. Each of these flourishes (and many others) enhance the The Irishman’s rhythmic qualities. It’s not just the songs, but the film itself, that flows like a piece of music.