The most exciting Star Wars production in years isn’t a movie or a TV show

While Disney continues to milk the Star Wars universe, offering a never-ending supply of movies and television, one recent production—a virtual reality experience—stands out from the rest, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

The original Star Wars dished up screen-buckling spectacle on a hitherto unrealised scale, powered by various behind-the-scenes innovations such as the first digitally controlled camera systems. Subsequent Star Wars productions have continued a history of technological developments, including a new kind of virtual scaffolding created for The Mandalorian.

Read more

* A deep dive into the cinematic beauty of The Last of Us Part 2

* All new movies & shows to stream

But in the hands of Disney, which acquired the franchise in 2012, tales from the galaxy far far away have been bogged down by a sense of same-old same-old: a twisted family dynamic here; the clanging of lightsabers and spitting of laser beams over there. In this sense it’s unsurprising that the first Star Wars production in god knows how long to offer a genuine feeling of wonder—the kind of buzz that comes not just from what is realised on screen but what is possible—isn’t a movie or a TV show.

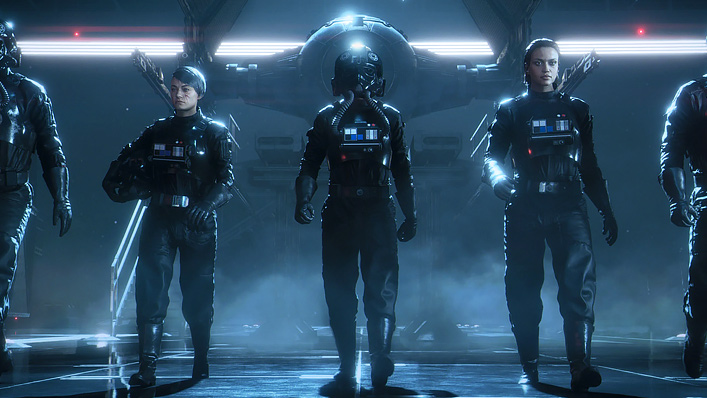

It is the virtual reality experience Star Wars: Squadrons on PSVR. In this exhilarating game the player—alternating between fighting for the New Republic and the Empire—plonks their butt into the virtual cockpit of an X-Wing, or a TIE fighter, or a number of other snazzy ships, and whooshes about participating in dogfights and various missions.

Whooshing around, trying to kill Alderaanians

There is a core paradox to space simulators that is also a core paradox of virtual reality: that of constant movement—the feeling of being able to go anywhere—contrasted with the immobile state of the real-life participant. That is always true in VR, but particularly pronounced in experiences like Squadrons, where characters in the narrative world are as bound to their immediate environment as the VR user is to their headset.

The story begins immediately after events depicted in A New Hope: namely the destruction of Princess Leia’s home planet of Alderaan. Darth Vader orders his troops to track down and kill all remaining Alderaanians, who are “refugees from a world we destroyed”—as Lindon Javes (voiced by Phil Morris) puts it. The task proves too much for Javes, who defects mid-mission and joins the Rebels, making a sworn enemy of his colleague Terisa Kerrill (voiced by Peta Sergeant).

Their rivalry and eventual confrontation is the main narrative arc that stretches over the campaign running time, though individual missions (which include destroying certain ships and escorting convoys) aren’t necessarily related. The player is an observer rather than an agent in the narrative—meaning we passively absorb exposition and backstory, primarily delivered by characters who talk to each other during missions and deliver non-interactive monologues between them.

Wowza, they’re some good reviews

Squadrons (which is available on other consoles but is something else—truly taking flight—in VR) has generated a very positive reception. Boosted by the Star Wars brand, coverage spilled over from VR-focused publications to tech and even mainstream publications. “Star Wars Squadrons has almost made me a VR convert,” reads the headline to a gushing piece on TechRadar. Meanwhile Engadget described it as a “perfectly pitched VR game,” CNet as “the great VR game you’ve been waiting for,” and The Guardian as “childhood-fantasy fulfilment on a galactic scale.”

That last description is on the money: who of us watched Star Wars and didn’t want to sit inside the cockpit of a TIE fighter or an X-Wing? The heart of Squadrons exists in this space, with the player surrounded by all sorts of buttons, dials and screens and a striking outer space tableau ahead—from clouds tinged in the glow of orange suns to planets with bright electric green atmospheres.

It’s not perfect—but it’s pretty damn exciting

But a perfectly pitched VR game? Or a great VR game? As exciting as it is, Squadrons is neither of those things. As a VR narrative experience the first obvious drawback is the presentation of cutscenes on flat 2D screens throughout the 10 or so hour story mode. EA obviously chose to do this for cross compatibility, given the game is available on multiple consoles and producing these scenes in immersive 360 would require a fundamentally different approach.

The strive to define what this fundamentally different approach is—and how to achieve it—is what makes the medium so challenging for storytellers, and such an interesting space to discuss narrative. Content creators need to redefine the language for motion picture storytelling, developed and finessed since cinema arrived in the late 1800s, to address new challenges including the most basic one: how to direct the audience’s attention in a 360 environment.

There are many methods to achieve this. Blocking, for instance: a technique that originated in theatre involving drawing sightlines, using the positioning of actors to convey mood as well as visual direction. And lighting effects can be strikingly powerful, some VR experiences blackening out swathes of the virtual environment and illuminating others in order to frame where the important cues take place.

The core challenge of VR is all about 360 worlds

Abandoning 360 means abandoning the core feature of virtual reality; no great VR production does this. The ones that do—like Squadrons and the recent Blair Witch VR—are often ports, and always lacking. But those cockpit moments? They’re gold. I found controlling the various ships in Squadrons difficult and a pretty steep learning curve. But there’s a purity in the gameplay that generates real wow factor, and gets one’s head moving and tilting and rolling—a big, stupid, slack-jawed smile beneath the VR headset.

These cockpit experiences are what cause writers to leap towards hyperbole. Is it a historical accident that they are so effective, and that flight simulators have been so fundamental in the evolution of VR? First produced in the 1930s, The Link Trainer flight simulator—essentially a cockpit mounted on a moveable platform, which was used to train World War II era pilots—became, to borrow the words of author Howard Rheingold (from his 1991 book Virtual Reality), “one of the key historical antecedents of VR.”

There are many interesting connections between flight simulations and virtual reality—the tech pioneer Ivan Sutherland for instance being a huge force behind modern flight simulators, and also the co-creator of one of the first head mounted VR display systems. But there’s a lot to go into here; a conversation for another time. For now, jump into a Squadrons cockpit, if you can, and take one of the ships for a spin. In true VR style, you’ll go everywhere and you’ll go nowhere.