The Boys made me revisit the greatest superhero scene of all time, from Zack Snyder’s Watchmen

Amazon Prime’s off-the-wall series The Boys is the latest dark and dirty superhero production. Luke Buckmaster explores the show and explains why it drew back him to the best superhero scene of all time, from Zack Snyder’s 2009 epic Watchmen.

It can no longer be considered an act of originality or subversiveness to tell a dark and cynical story about superheroes breaking bad. Or, as the case may be in Amazon’s eight part series The Boys, superheroes who were never good in the first place, and thus were never really heroes – if indeed any meaning can be derived from such binary definitions. This show is full of grey areas. And also full of a fantastical array of grotesqueries – from dolphin erotica to a seduction-gone-wrong that results in a man’s head being crushed while giving a super-enabled woman head.

That, by the way, is the nomenclature preferred in this world. The costumed crusaders are “super-enabled” rather than “superheroes” – a distinction that goes some way in reflecting the show’s core cynicism. The story revolves around a group of such “enabled” folk called the Seven, who are deeply flawed individuals to say the least. Some of them fiends, drug addicts and sex offenders, and all of them stooges for the organsiation to which they belong: Vought International, a multibillion-dollar corporation that cares about political power – not any romantic ideals about doing “right” or “wrong.”

A seedy, corrosive kind of energy washes over the drama, like the Kick-Ass films or the 2010 black comedy Super. But of this canon of films – bizarro superhero movies that ferociously subvert those quaint, old school ‘undies on the outside’ stories – one work towers above the rest: director Zack Snyder’s 2009 epic Watchmen, a terrific adaptation of comic book writer Alan Moore’s seminal graphic novel. The Boys bears many similarities to Watchmen. I have never another film or TV show that expands so many of its ideas and exists in such a similar space.

Never, also, have I seen another film or TV show that’s entire existence – its very raison d’etre – is so succinctly captured in Watchmen’s unforgettable opening credits sequence. In this scene, a five and a half minute montage of slow-mo vignettes set to the tune of Bob Dylan’s iconic protest anthem The Times They Are A-Changin’, Snyder says more than The Boys expresses in approximately eight hours of running time.

That is less a criticism of the show (which I liked, and which grew on me as it progressed) than a reminder of how good the Watchmen sequence is: to my mind, it’s the greatest superhero scene in motion picture history. What other stretch of film or television could compete with its thrilling revisionism and postmodern ideas, its pressure-packed meanings, its brilliant reinterpretation of historical narratives through the prism of pop culture’s infinite cycle?

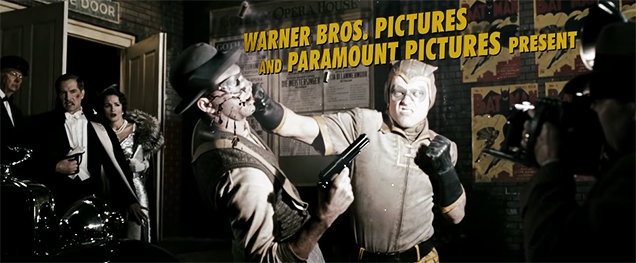

The first shot – depicting a superhero called Nite Owl punching out a gun-brandishing robber – presents a paradox. Batman posters in the background indicate this is about the Dark Knight, identifying the two well-to-do theatregoers on the left of the frame as Bruce Wayne’s parents. Who, in this revised storyline, are saved from being murdered, meaning Batman (whose backstory involves witnessing their death as a child) never came to be. Contradictions aside, this is interesting visual storytelling and clever use of space, the right side of the frame providing the context with which to view the left and central elements.

A vignette one minute in reconfigures the circumstances around the taking of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic photographic, which captured a uniformed sailor kissing a woman in a white dress immediately following the declaration of the end of World War II. In Watchmen it is now a woman, Silhouette, roaming around looking for liplock, kissing an acquiescent woman in white – whose back, like in Eisenstaedt’s photograph, arches dramatically backwards.

It is a striking moment of LGBT celebration that proves shockingly short-lived, with a message about how victories in the LGBT movement have been hard-fought and involve the spilling of real blood. We next see the two women lying on a bed together, brutally murdered. The words “LESBIAN WHORES” are written on the wall behind them in their own smeared blood. Meanwhile on the soundtrack Dylan croons: “You’re sons and your daughters are beyond your command, your old road is happening ageing.”

For me the entire meaning of this classic song – and to an extent the meaning of Snyder’s sequence – can be derived from the next line: “Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand.” In a world that is constantly changing, Dylan argues, it is a moral imperative to be supportive rather than destructive on the path to meaningful social progress – or at the very least to shut up and get out of the way. This evokes real-world situations involving conservative forces attempting to fight the inevitability of progress, armed with the decaying philosophies of yesteryear (often found in passé attitudes towards social issues such as drug use, abortion and LGBT rights).

At another point in Watchmen’s opening credits, we see a male superhero (Dollar Bill) shot dead, slumped on the ground outside a bank. His cape is stuck in the door, presumably rendering him immobile and allowing him to be killed by robbers. What are superhero capes, other than forms of branding? There is much conversation in The Boys about how the Seven are connected to consumerism in general and advertising affiliations in particular, exploring the concept of branding heroism (also touched on recently in The Incredibles 2 and Spider-Man: Far From Home). In just a few seconds, Snyder shows us how a person can be killed by their own marketing.

This extraordinary sequence also depicts several historical moments, rewritten to include the involvement of various parties. The Comedian (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) for instance is implicated in the murder of JFK, and Doctor Manhattan (Billy Crudup) is present on the moon when Neil Armstrong took his giant leap for mankind. Snyder reinvents other moments that linger in the public consciousness, including a dinner party shot homaging Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

These aren’t simple cut and paste jobs about inserting characters here and there; the process means much more than that. By placing these characters inside significant real-life events, Snyder makes a point about how humans arrange the data of our lives, and collective experiences, by telling stories. It is a way of making sense of the fabric of the universe. As Jean-Luc Godard once said: “Sometimes reality is too complex. Stories give it meaning.” Or even, as Joan Didion put it: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

In the real world, history is distorted by legend – the fidelity of facts obscured by the smoke of campfire type storytelling, in whatever form that takes. Watchmen errs towards making the opposite point: suggesting history has obscured legend, writing out the magical forces that contributed to great moments of cultural significance. There is a melancholic sentiment underneath all of this, expressed in many of the vignettes, about how time can have a corrosive effect on everything – even the nature of virtue. “You either die a hero,” as Harvey Dent said in The Dark Knight, “or live long enough to see yourself become a villain.”

What a scene! This fascinating introduction could have been a lazy text crawl, like the kind in Star Wars, but instead it became a truly striking example of that old dictum ‘show don’t tell’. I started this piece intending to write about The Boys, but Snyder and his band of flawed idiosyncratic heroes (can we even call them heroes?) drew me back like a magnet to their world of moral greys and complex ideologies, and to that very dense intro scene in particular.

One of the reasons why Watchmen and The Boys (the former more than the latter) are such interesting texts is because, in their world as in ours, morality comes down to individual perception, and perceptions can differ sharply from person to person. That is true of many films, contrasting for instance the hero’s principles with the villain’s objectives. But in these stories it is particularly complex, because the moral centre, as it were, cannot hold; morality itself is fluid. There are no such things as heroes and villains: only different people – whether they are “super-enabled” or whether they are just jerks – holding themselves to different standards.