Interview: ‘Best of Enemies’ (Screening at MIFF 2015)

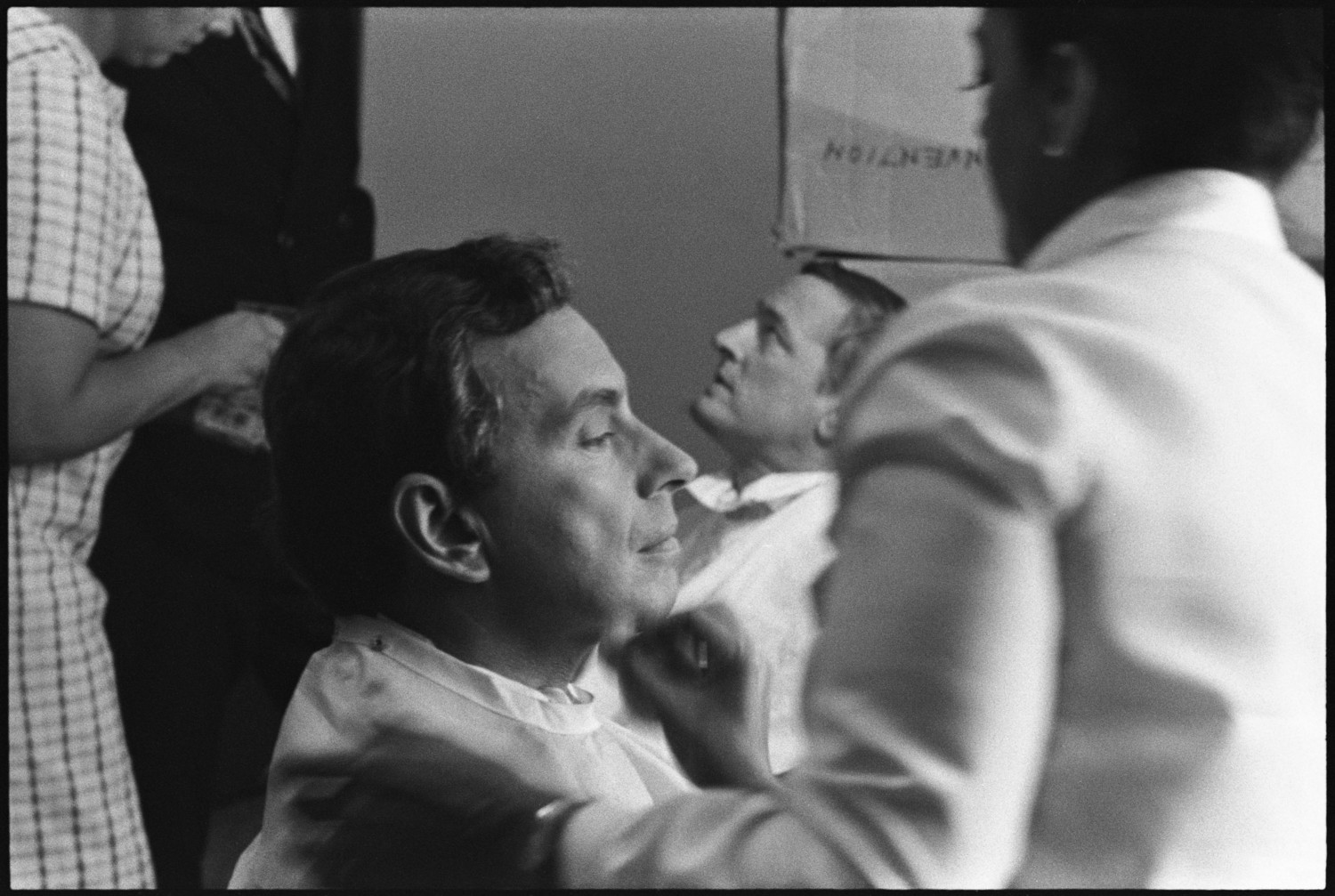

Best of Enemies, screening at the Melbourne International Film Festival, looks back at televised debates between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley.

Dry as that sounds, their match-ups during the Democratic and Republican National Conventions of 1968 helped shape the combative style of political coverage right through to the present.

For ten nights, the ideologically opposed intellectuals scrapped, in a no-holds-barred contest of ideas and insults that rivaled the finest proponents of pugilism – not that most boxers ever hated each other as much as these two did…

We spoke to co-director Morgan Neville, who’d just arrived in Washington D.C. ahead of a screening of his fascinating film.

See our 20 must-see MIFF films here.

FLIKS: I can’t think of a better place to be speaking to you about a movie that’s so woven into American politics, or vice-versa.

MORGAN NEVILLE: And that’s why I’m here. We’re premiering in D.C. tonight. It’s the AFI Documentary Festival and we’re the opening night film. It’s going to be a fun night.

What a fascinating story you’ve brought to the screen here…

Yeah, it’s one of these things. I think, I, like a lot of people of a certain age, were dimly aware of it. I was born in 1967, I knew who they were as characters. Buckley had a TV show forever. He was just a perennial American media figure. And Gore – I actually worked for Gore right out of college, as a fact checker. It was a thankless job that I survived [chuckles]. But Gore’s a fascinating character too.

Really what it came down to, the origin of the film, is that Robert Gordon, my co-director, had come across a bootleg of these debates, and a friend of his who is a professor screened them at his college for a class – just some raw debates – and he said the class practically got in to fisticuffs over it, and they were arguing and debating it afterwards.

He said “there’s something here” and he sent me a copy and I watched, and I was transfixed. So we knew there was something there just from the source material, but we didn’t really know where the story was going to go.

We spent some time shooting interviews just to figure out if there was even a documentary. We went and we did a round of interviews. The first interviews we did were Christopher Hitchens and Dick Cavett and Frank Rich.

After those interviews, we knew we had a film because basically they all saw in debates what we felt was in there – which is a much bigger story about TV and its role in our politics and our culture. About the decline of the public intellectual, and about civil and uncivil discourse.

There were a lot of things that I was really interested in and I have to say it was one of the most fun things I’ve ever worked on [chuckles]. To be able to luxuriate in these ideas, in these words and these characters was really a treat.

The footage really galvanizes your own leanings, even from half-way around the world as I am. To me, it’s just really interesting to see that the manner in which these debates influenced current affairs is another American cultural export. Do you feel that way?

I do. I hate to take claim for such an export from the country [chuckles].

It’s okay, it’s okay. It’s just one of many terrible exports out of the United States.

No, you can pile on it. The film’s only screened in a couple of places outside of the United States, and so it’s interesting to see how it translates, as it were.

It works on a couple of levels. I think people recognize something about their own political and media landscapes – maybe not as bitter and vitriolic as we have here in America – but certainly traces of that exist everywhere, and maybe that’s America’s fault.

But also, I think, on another level, to me I keep thinking of it as an opera [chuckles]. These two characters who are both kind of heroic and tragic at the same time – certainly heroic in their own minds – but just the size of their personalities. They’re just characters that don’t exist much, if at all, any more in our world. So, in a way, I hope the film works on that level, and hopefully it does. We’ll see how it plays down there.

Before bringing those two gentlemen together for the debates, obviously, nothing like that had really been seen before. Was the landscape one that was largely one-on-one interviews and polemic-based discussion?

Yes, and basically the news would have occasional commentaries of somebody opining sagely about a subject and, beyond that, it was talk shows which, for the most part, were pretty civil. We had the Jack Carrs, and then Dick Cavett started right about this time – 1968 on ABC2.

I think culture, in general, was much more civil, and certainly there was this veneer of civility.

The uncomfortable things that existed in our culture were, for the most part, not on television. Those people – the Malcolm Xs – weren’t given a lot of time and then when they were on TV, they were treated as extremists and radicals, but never taken seriously.

Do you see a parallel in terms of the cultural impact with the first televised debates between Kennedy and Nixon?

I do and, in a way, it’s a part of this bigger cultural story that I was talking about at the beginning which is what does TV do to our democracy? How does it affect it? And it’s all those obvious things that came out of the Kennedy-Nixon debate and continue to this day, which is the image of over substance, in a very simplistic way, but just I think that the essence of an idea is not the important thing – it’s the articulation of it. And that TV rewards the quick joust, and something that plays well, whether or not the idea’s good.

Frankly, Buckley was a master at that. I really think that Buckley’s first love was debate, not politics. I think he loved debating anything and politics gave him a great life-long field of debate. I really think he loved the game of debate, and certainly Gore did too, to some extent.

I think that’s why they were so combustible to each other, but normally they were used to taking other people apart. You’d have people like a Noam Chomsky – thoughtful, intelligent opponents – come on Buckley’s show and whether or not their ideas were sound, he could make them look foolish because he was a master at picking apart the way people articulated, not fighting about ideas, but fighting about the image of ideas, or the way things articulated.

That is something that I think TV rewards, certainly in a way that print doesn’t, and that’s the legacy we’re still dealing with.

When reducing a discourse to spectacle – which is the end result of this process – what’s the most dangerous part of that for a democracy?

It’s interesting. There’s another documentary called Merchants of Doubt that came out just this past year that made me think about this a lot. It was Robbie Kenner, who did Food Inc., directed it, and it’s about the whole industry of these fake pundits that go on TV to do things like debunk climate change and defend Big Tobacco.

These guys aren’t scientists, and they’re not even particularly knowledgeable, but they’re brilliant at verbal gymnastics. I think that’s the dangerous thing, is that our media tends to, and maybe it’s even just the human nature thing, but media certainly tends to have these false equivalencies where you present all opinions as equal, and give equal time, and I think what a lot of times the person who’s the better debater somehow feels like he has the better ideas. I think TV rewards that and that leads to a lot of misinformation and a lot of things we just can’t agree about any more.

To me, the most pernicious thing about the legacy of this, and what’s lost and what’s gained, is that we live in a world – it’s kind of where we ended the film – we now don’t have to confront people we don’t agree with. We just reinforce our own ideas, and it’s one thing to not be confronted with other opinions, but we can’t agree on anything approaching subjective fact. And when we can’t agree on truth, that’s a dangerous slope to be on, and I think it’s one we’re on right now.

You used the phrase verbal gymnastics a minute ago and I just wanted to compliment you on the verbal gymnasts that you have reading – John Lithgow and Kesley Grammer – that’s such incredible casting to really help bring these characters to life even more.

Yeah, we debated and debated how exactly to handle that, and when we came up with the idea of doing them, they were just so perfect [chuckles] and one’s a Liberal, one’s a Conservative. They embodied those characters. That was fantastic.

Well, it was a fascinating film that I really enjoyed watching last night. Interestingly, earlier in the evening, I watched Russell Brand’s financial crisis film, so it was definitely a 40/50 year span of different media portrayals of current events last night.

You got a very interesting double feature. Sounds good.

Best of Enemies screens at MIFF on August 2nd and 16th, tickets here.

See our 20 must-see MIFF films here.