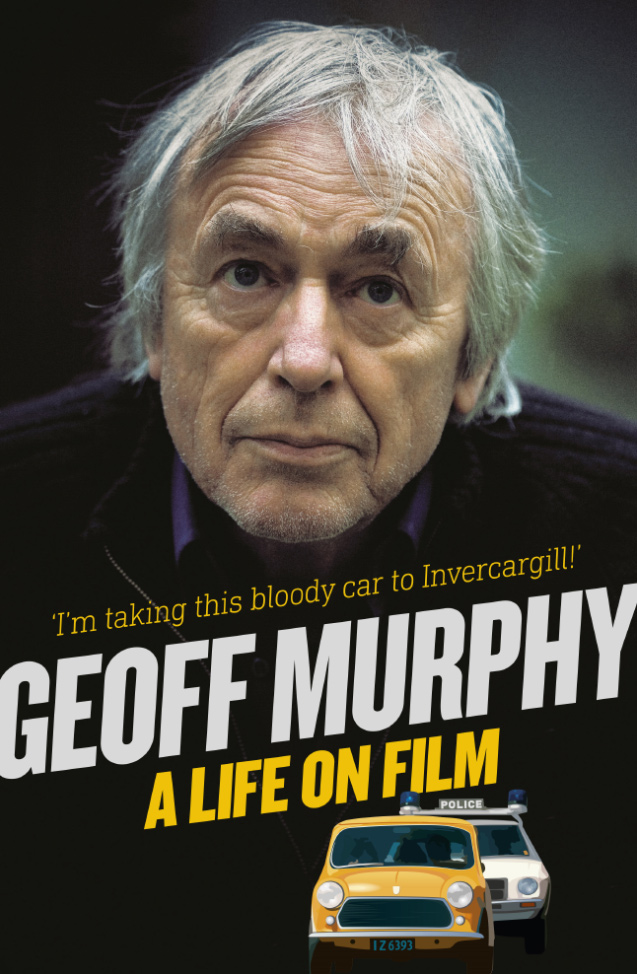

Remembering Geoff Murphy with one of his tallest Hollywood tales

We’re saddened today to hear cherished Kiwi filming icon Geoff Murphy has passed away. His colourful life and career brought joy to so many of us. As you’d imagine from someone who emerged into public view as a part of the counter-culture creative collective BLERTA, director of the anarchic, groundbreaking Goodbye Pork Pie and went on to adventures (perhaps misadventures) in Hollywood, Murphy had many a tall tale to tell.

Earlier this year, we were surprised that alongside bona fide 80s classics The Quiet Earth and Utu, Murphy had nearly directed 1987’s Predator. It’s just one of the stories in his memoir Geoff Murphy: A Life on Film that we share again with you today, a tale that might not have ended successfully but captures Murphy’s quintessential Kiwi-ness, including having no worries about taking the piss out of himself.

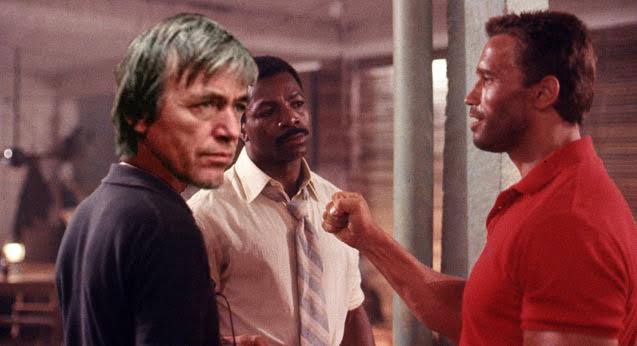

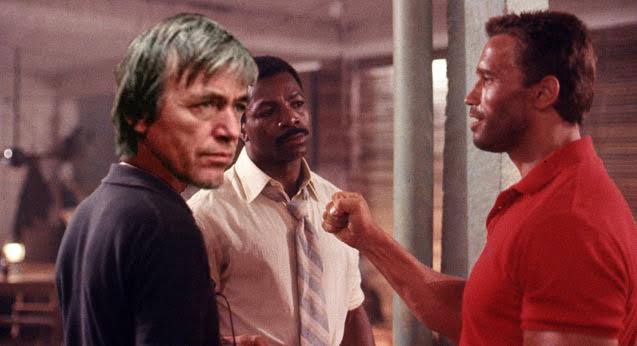

With the kind permission of publisher HarperCollins New Zealand, this extract from Murphy’s memoir recounts his time on the project—and unexpectedly foot-in-mouth exit. We’ve taken the liberty of adding a few doctored pics to illustrate how things could have gone differently…

Murphy’s tale commences on the heels of ultimately unsuccessful meetings about directing Conan the Barbarian, Part III and Surf Nazis Must Die.

This meeting went a lot better. For a start, this project had a script. Bill [Block – Murphy’s Hollywood agent] had sent it to me in Auckland just before I left for Sydney to mix The Quiet Earth. I read and enjoyed it. It was called The Hunter. I had expressed interest in it then.

We met with the writers and a Fox executive to discuss the project, and I immediately expressed my interest. Bill went off with the Fox guy to hammer out a deal, and the writers and I went off to a bar and had a drink. These writers were the Thomas brothers, John and Jim. They were genuine Californians, born and bred, and had both worked for some time as surf lifesavers on the Pacific coast. This was their first script, and it was an early draft. It is notoriously difficult to get anyone to read a script in Hollywood, so they were somewhat taken aback to have one that was already being slated for production. I got on really well with them, which was just as well, as any deal that Bill managed to pull off would probably have all three of us crammed in a small room for several months as we polished the script up ready for production.

The deals were done quite quickly, and we were allocated a room at the back of the Twentieth Century Fox lot. I had a pay- or-play deal to direct The Hunter for some US$150,000. This sounded a hell of a lot to me. ‘Pay-or-play’ means that if the studio decides after a time that they are no longer interested in making the film, or if they fire me, I would get paid the full amount as though I had directed the picture. It was as good as money in the bank! If I broke the contract, I would get nothing and maybe even lay myself open to being sued. This was not likely. This Bill Block joker seemed to know what he was about. Of course he took 10 per cent, but he was worth it. I don’t know what sort of deal the writers got, but I’m sure it was pretty good, so the three of us settled down in our little room and set to work. There was just the three of us, no producer, no secretary or anything like that. We were a lean machine, reporting from time to time to the Fox executives who were allocated to our project. We were happy chappies.

We agreed pretty quickly that the basic shape and theme of the script were fine. Our job was to flesh out the characters and detail and add a polish.

I thought the set-up as written was really good. In the title sequence a spaceship descends from the heavens and settles in a small jungle clearing. It is only a modest-sized spaceship and looks a bit grimy and fairly battered, like an old, much-used farm Land Rover. It sits there emitting a low hum, and then it suddenly disappears. The hum, however, continues, and after a moment a wedge of light appears in the sky. The wedge widens and quickly we can see that it is a door that opens downwards, like an ancient drawbridge. We can see the interior of the invisible spaceship through the opening that the door has revealed. Inside, flickering displays and alien technology can be glimpsed. The inside of the door has steps on it, so that when it settles on the ground it forms a stairway into the invisible ship. A figure appears silhouetted against the brightly lit interior. It moves sinuously down the stairs and stands there, glinting in the moonlight. It has a gadget in its hand, and with a flick of its wrist the stairs retract and the door closes, leaving no sign of the spaceship. The figure flicks the gadget again, and he himself disappears.

This alien that has arrived is the hunter. He has similar characteristics to the big-game hunters who used to plague Africa. He hunts for sport: the more dangerous the prey, the greater the sport. Like the great white hunter standing with his gun raised in the face of a charging rhino, he likes to offer his victims a glimmer of a chance, but only a glimmer. He likes to take part of his prey back home with him as a trophy, an example of his skill and bravery. He has chosen the Earth from all the planets in the galaxy, and landed to hunt the most dangerous animal that his instruments have yet detected.

Man.

We didn’t have to do much to improve on this guy. He was pretty good from the start. The humans required more work, and we wrote and rewrote for the next three months until we were happy that we had developed a worthy protagonist.

Our hero is the leader of a Navy SEAL team of about 10 men. They are equipped with the most efficient and fearsome weapons known to man, and have been trained as a unit until each man can sense where the others are and what they are doing without looking. They are super-fit, and their training has been about honing their every instinct for war.

Their leader is a special kind of soldier. His grandfather had served with distinction in World War I, and his father had survived the cauldron of the Normandy landings and the Battle of the Bulge. He was born to be a soldier. But there was one thing that had always worried him. It was easy to identify the enemy in the days of his forefathers. The Kaiser’s troops, with their pointed helmets and lust for world dominance, and even more so the Nazis, with their swastikas, squat panzer tanks, vulture-like Stuka dive-bombers and their penchant for genocide, were clearly the forces of evil. They demanded to be confronted. To fail to do so would be a dereliction of one’s duty to the human race. However, with each post-war conflict, the picture had become more murky. The US Government were no longer the white hats they had always been. The President told lies, and US troops were known to have committed atrocities. The ethics of the military ethos had taken a severe battering. This is why he chose the Navy SEALs. Here was a unit that had been created to combat bearded terrorists who hi-jack planes with the intention of killing innocent civilians in their seats. Here was an enemy he could identify and that demanded confrontation. So he threw himself into his training, seeking to become the best of the best.

However, when the word came for his first mission, it was not to rescue hostages from salivating fanatics at all. It was a very puzzling brief. Somewhere in Central America, someone was going about disembowelling, skinning and decapitating people and hanging their bodies in trees. This could have passed unnoticed if it weren’t for the fact that a couple of the victims had been from the American military, and the incidents had all the hallmarks of terrorism. Of course officially there were no American military personnel in Central America, but the fact that someone had actually caught them was worrisome to the establishment, and so it was decided to send a hot-shot team down there to investigate their deaths. Thus it was that our hero got the word. I had always imagined that someone like Harrison Ford would play this part.

Unfortunately, the powers that be insisted that a CIA operative accompany them. Harrison objected for three reasons. He didn’t like the CIA, he didn’t like this particular operative (I imagined James Woods would play him), but mostly he felt that an extra person would upset the finely tuned machine that his SEAL team had become after several years of intensive training. He was overruled, and before long they were being dropped off by a Navy chopper in the middle of the jungle.

If you haven’t guessed it already, this film was later made as Predator and starred Arnold Schwarzenegger, and was not directed by me, but more of that later.

They duly find the bodies, and, searching for the perpetrator of this heinous crime, set about attacking a guerilla camp they discover nearby. We had it that they make short work of this camp and enter it only to discover that it was defended by old men and boys. It was not a frontline camp at all, but a supply depot manned by non-combatants.

When we submitted our script to the studio executives, we learned that this concept was not acceptable. I was informed that all guerillas look like a cross between Fidel Castro and the Hell’s Angels, only uglier, and American soldiers don’t shoot old men and boys. This was after the My Lai massacre — everyone knew that American soldiers did shoot old men and boys. They also shot women and girls. ‘Do you guys work for the State Department?’ I asked. They replied that they did not. They had no interest in politics, they were only interested in what sells, and that’s how guerillas had to look if they hoped to sell the movie to the American public. When it came to American culture, I still had a fair bit to learn.

The studio heads also rejected the idea that the alien was a woman. They figured that in the 1980s 17-year-old boys were not willing to accept that a woman could kick the ass of an entire US Navy SEAL team, even if she was wearing a fancy suit. We tried them on the idea of the alien being an old man, like a 150-year-old guy, thus still maintaining its frailty but avoiding it being a woman. They didn’t like this either. They wanted an ugly alien. They didn’t like the idea that mankind’s foes could be beautiful or fragile. The American public wouldn’t buy it. In the end they went for the standard rubber alien.

Towards the end of the writing period, Twentieth Century Fox decided to employ a producer for the project, so they hired a guy called Joel Silver. Joel ticked all their boxes. He had made several successful action films, was a testosterone producer, and was Jewish. Mostly I got on okay with him, but we did have a number of difficult conversations. The key one was about the casting. Joel was keen to cast Arnold Schwarzenegger as the lead. I felt that he was wrong. The lead we had written was the quintessential American GI. You couldn’t cast an Austrian. He couldn’t even speak English properly. Joel informed me that Arnold was just finishing a film called Commando which was due to open soon. ‘If Commando takes 20 million on its opening weekend, Arnold will play the lead.’ There would be no argument. The dollar sign is the bottom line. Get used to it. Realising that there was no way around this one, I agreed to it, provided we could rewrite the script. If Arnie didn’t fit the script, then we would have to make the script fit Arnie.

I now had a few weeks with nothing to do, so I flew back to Auckland. In due course I got a call from Bill Block informing me that I had been fired. Arnie had agreed to do the film, but his contract gave him right of approval of the director. He didn’t want me. He wanted John McTiernan.

I was pretty disappointed, as I had got pretty fond of this script. Still, he’s no fool, is Arnie. I presumed that Joel Silver had told him of my reservations, and he had acted accordingly. John was a good choice. He had made the first (and the best) Die Hard. He’s a damned good director.

The sequel to this came sometime later. Bill called me about a development contract. This is where you are paid to work as a director with a writer on the script with no guarantee that the film would be made. This is not a pay-or-play deal. These contracts were quite common, and quite a few people made a good living from them even when the films were never made. In this case, the producer was my old mate Joel Silver and he wanted to develop a film about Wild Bill Hickok. The idea didn’t grab me at the time, and I was still a bit raw over Joel’s supposed role in my sacking, so I told Bill to tell him that I didn’t want to work with him as he was an arsehole and had got me fired off Predator.

Well, Bill did just that. He reported back that Joel was very pissed off. He claimed that he didn’t get me fired off Predator at all, Arnie had done that himself. He had fired me because someone had told him that when I was meeting with Dino [about Conan III] I had referred to him as Cronin the Librarian! Evidently Mr Schwarzenegger is a very sensitive soul. He had every right to fire me. Arnie had the right of approval of the director for Predator written into his contract.

So that is how I blew probably the biggest break I could ever have got in Hollywood. It was my big mouth!