Fight Club 20 years on: how does its politics stand up?

Fight Club blew people’s minds when it arrived in cinemas in 1999. But a lot has changed in the world since Tyler Durden burst upon the scene – and a once gut-busting film isn’t what it used to be, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

When director David Fincher’s fiendishly stylish provocation Fight Club arrived in 1999, a cyclonic force seemed to accompany the film’s release; it was as if a wild storm had pushed it into cinemas. Watching this high-wired drama/thriller – with its explosive anti-capitalist messages and stench of violent, risqué rebellion – felt intensely visceral. Pre-millenium tension billowed out of it like hot air from an oven door.

The film electrified me, throwing me down the rabbit hole of novelist Chuck Palahniuk’s oeuvre, the author who wrote the book on which it is based. The author’s whiplash-inducing prose is often lifted verbatim and placed directly into the mouth of a protagonist known only as Narrator (Edward Norton), an insurance assessor whose existence is upturned by the charismatic lifestyle anarchist Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), the kind of guy whose idea of a perfect European vacation involves firebombing the Louvre and wiping his arse with the Mona Lisa.

When it is revealed (spoiler alert!) that Durden is a split personality inside the Narrator’s head, the film throws mental illness into its basket of motley messages and contentious themes. With his unbearably cool retro style (loud leather jackets, shirts with huge lapels, bug-eyed sunglasses etcetera), Durden could be considered an unintended offshoot of the market forces he is rebelling against: a sort of an anti-materialist, soap-selling materialist; chic and iconoclastic in anti-icon kind of way.

A symbol, in other words, of dissent and nonconformity. Durden described his generation (no doubt including himself) as “by-products of a lifestyle obsession,” famously warning the Narrator that “the things you own end up owning you.”

Fight Club attacked neoliberalism before it was cool

The film (and of course the book) took a shot at neoliberalism before it was cool, suggesting the very essence of capitalism was fouling our society, ensconcing it in a mushroom cloud of injustice and inequality. In subsequent years, neoliberalism would be fingered by areas of the commentariat (this George Monbiot piece from The Guardian one of many examples) as the adhesive binding together a seemingly random cavalcade of disastrous 21st century movements and inflection points – from the GFC to the election of Donald Trump and even the rise of the alt-right.

Durden doesn’t get bogged down in specifics; if he knew what neoliberalism was, he probably would have dismissed it as a fancy word used by academics who spend their lives writing books nobody reads. The hyper masculine cosmopolitan insurgent, presiding over a gang of disenfranchised thugs who probably went on to become men’s rights activists, always intended to tap into general disaffection rather than propose a specific doctrine or action plan, beyond baseless pranksterism and violence. The “homework” assignments Durden gave his minions (such as removing the barcodes from all videos in a rental store) feel like a kind of cruel version of flashmobs – another phenomenon that emerged out of the cultural malaise of the 1990s.

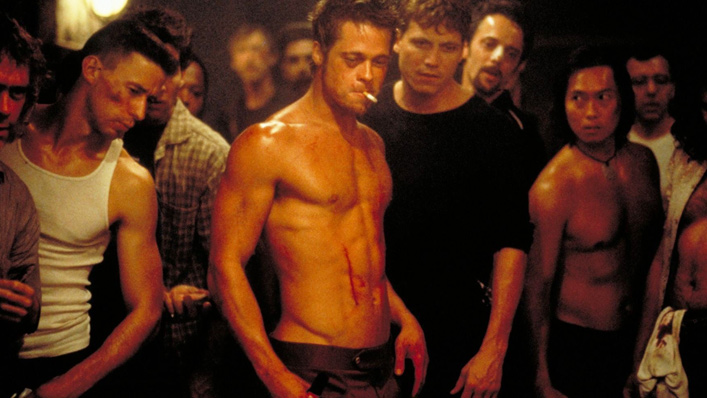

Like Harvey Dent in Joker, Durden surveyed the bureaucracy of politics and shortcomings of capitalism and saw a system to burn down – not a game to play or a world to heal. If Fight Club has a central, unifying speech – a core that underlines Durden’s political attitudes and gives the film a philosophical anchor – it would be the following famous spiel, delivered by a banged-up and topless Brad Pitt, stomping around in a basement like a wild virile animal:

“We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war. Our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Tyler Durden didn’t know how good he had it

This bile-scented speech resonated like biblical truth at the time: to the crowd in the basement as well as contingents of the viewing audience. But, rewatching the film today, I felt like grabbing Durden by the scruff of his bloodied neck and saying to him: dude (or even: “OK boomer” – yes, Brad Pitt is a boomer) you don’t know how lucky you had it, being one of the “middle children of history, man,” dealing with how your Great War is “spiritual” and all that. I’m so sorry you and your gen were “very pissed off” because TV duped you.

Want to know what it feels like to really have something to be angry about, with relation to social power dynamics and people thrown to the dogs by the lords of neoliberalism? Go ask the youth of today, man, who have a lot more troubling things on their minds than the phoney promises beamed out of an idiot box. These people long for a time when grim realisation meant acknowledging they might not grow up to be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars.

In the thick of the climate crisis, today’s youth are forced to acknowledge the planet they live on – with everything that comes with it, including the very air they breathe – is at best becoming a polluted shell of what it once was, and at worst a ticking time bomb leading to the collapse of human civilisation.

The disaffection of the 90s ain’t got nuthin’ on today

Add to that the rise of the surveillance state, the housing crisis, the robot revolution, the re-emergence of fascism, the last days of reality etcetera etcetera – and now, suddenly, complaining about being a byproduct of this or that – a soldier in some vaguely defined spiritual war – doesn’t seem to mean all that much, does it, man?

In the current day and age the whining Durden and his minions seem privileged, not oppressed. Their charismatic leader’s rhetoric suggests they are worker drones, slaving away for the powers that be. But the Narrator, their leader, has a cushy well-paying office job and money to burn, with an apartment full of crap he doesn’t need. Coupled with the vagueness of their rebellion – these guys know they’re fighting, but they don’t bother defining what they’re fighting for – Fight Club now, in 2019, feels like a younger and coarser person’s equivalent of the old man yells at cloud meme. Stupid, baseless, undirected rage. Anger for the sake of it.

I loved the film at the time, and am still very fond of elements of it today – particularly its extensive and terrifically written narration, for which we must credit Palahniuk. But the sting of the film is gone. So is that cyclonic, face-peeling momentum that seemed to push it onto our screens. Fight Club is increasingly becoming an argument against its own characters and even its own premise. History seems to be looking back on those time-wasting hotheads bashing each other up in the basement, and saying: you guys had it pretty good, after all.