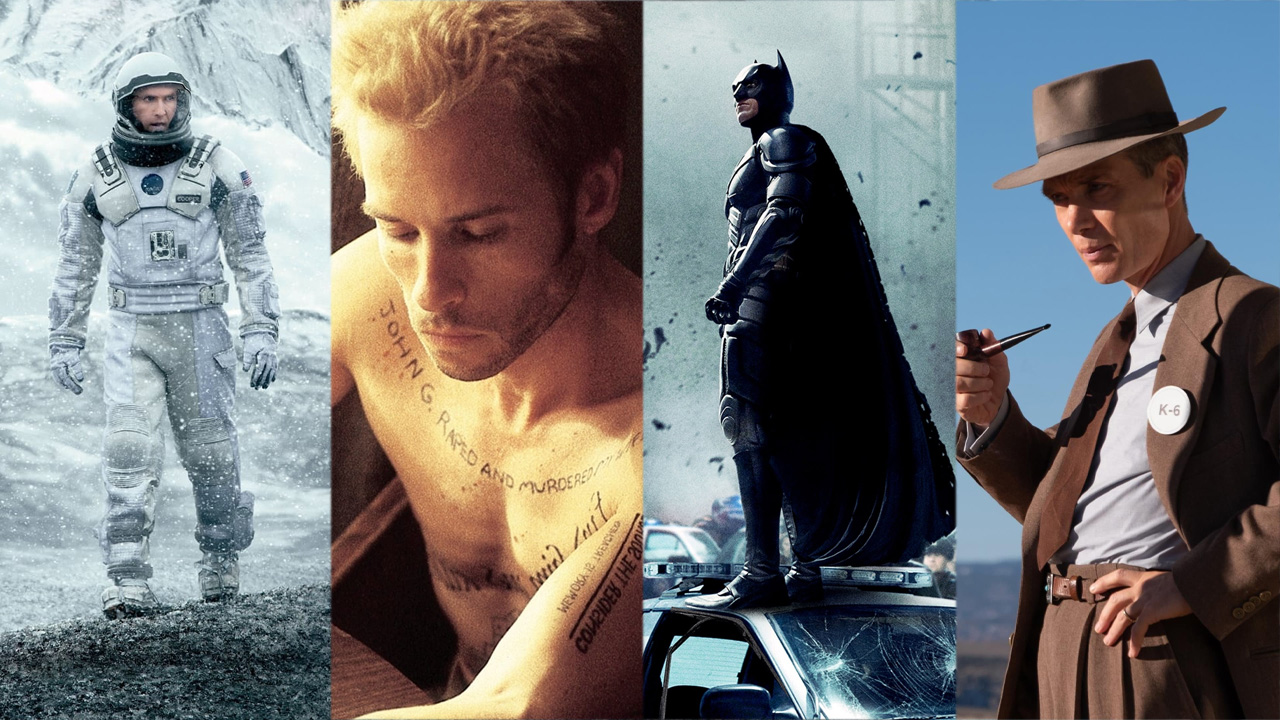

Every Christopher Nolan movie, ranked from worst to best

These days Christopher Nolan is a rare breed of filmmaker, capable of turning original concepts into blockbuster event movies. He’s dabbled with superhero shenanigans, via the Batman movies, but emerged with his style and verve undiminished. Over the last quarter century, the British writer/director has made a couple of clunkers, a couple of masterpieces, and numerous films in between.

Here’s all his movies, ranked from worst to best.

12. Tenet (2020)

Sometimes Nolan’s dialogue errs towards student film psuedo profundity; in Tenet it spills right over. “Cause comes before effect,” John David Washington’s protagonist says early on, and indeed the dude has nailed it. But the snobby science lady demurs: “no, that’s just the way we see time.” He responds: “well, what about free will?” Yawn. Are we watching a movie or in high school philosophy class? None of it matters anyway when science lady goes full Jedi: “don’t try to understand it, feel it.”

The jibber-jabber strewn throughout Nolan’s outrageously perplexing spectacle, about saving the world from entropy and a maniacal Russian oligarch (Kenneth Branagh) who knows how to invert time, was worsened by well-known sound mixing issues, constituting one of modern cinema’s biggest technical stuff-ups. The second time I streamed it with subtitles, but it was still a slog. Moments of admittedly original choreography are smothered by the feeling that we’re watching a film trying awfully hard to be awfully clever for an awfully long time.

11. Batman Begins (2005)

Liam Neeson’s Ra’s al Ghul does marketing outreach for League of Shadows early in Batman Begins, monologuing to Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne about how he’s “become truly lost.” Sounds like he’s recruiting for a church. This moment has “origins” and “future legend” written all over it, but feels less like interesting drama than a box-ticking prologue. You could say the same about the film itself. When mentor Neeson and protege Bale fight with swords in a snowcapped exotic place, because cinematic, you can sense Nolan going through the motions.

There’s down ‘n dirty action in the second half, as the Bat nestles into Gotham City crime-fighting. One of his foes is Cillian Murphy’s Scarecrow, who innovatively attacks people by spraying them with intense hallucinogens then donning a freaking looking potato sack. And I thought I’d had a bad trip. He’s a pretty good villain, but for the final act Nolan returns to all that ho-hum legend stuff the film spent so long escaping.

10. Following (1999)

Nolan’s monochrome-veneered debut has the roughness and scratchiness of a future great artist finding their feet. Plus the buzz and sheer possibility of a future great artist finding their feet. I love the simplicity of its premise, which speaks to human idiosyncrasy: a man (Jeremy Theobald) follows people. Not for any particular reason: “I’d just see where they went, what they did.” One he follows is a burglar named Cobb (Alex Haw) who cottons on and confronts him. Soon they’re robbing homes together. Cobb says he does this for adrenaline, “and because like you I’m interested in people.”

Nolan is interested in people too: as catalysts for drama. The world is unfathomably large and complex, he seems to be saying, with potential stories everywhere. The houses you walk past on the way home could be getting robbed. Maybe someone’s being murdered. Following is more about the potential for interesting drama, because Nolan doesn’t manage to thread it into a satisfying experience. It’s not the cheap DIY aesthetic—it’s the script, the plot sequencing. The film doesn’t have good momentum or a satisfying denouement, and even at 70 minutes it feels sluggish.

9. Oppenheimer (2023)

If any film needed to get its moral messaging right, it’s one about the invention and deployment of the first nuclear weapons. We can’t help but react to the swelling score, the jagged cuts, the crescendoing energy, relayed with the nervy chutzpah of an Oliver Stone movie. There were lots of ways to tell this story…it didn’t need to be so juiced up. All the sound and fury means there’s no cool hand guiding the messaging. And while some of the staging is impressive, Nolan’s scrambled arrangement clips everything and rarely allows individual moments to breathe. He keeps whooshing away, scattering the pieces.

The presence of a more traditional villain, carved from American politics—Robert Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss, a bureaucrat serving in the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—wildly changes the film’s emphasis. It’s laughable to suggest Oppenheimer and Strauss’ moral crimes are comparable, but Nolan goes further than that, emphasising the latter’s chicanery in highlighter pen while the protagonist receives the soft glows of nuance. This film could’ve been richer if the director stopped slicing up his drama and configured well-developed moral and intellectual positions.

8. Interstellar (2014)

Nolan was always going to make a space movie—a rite of passage for blockbuster directors whose ambitions like this are: bigger, bigger, bigger. What nobody expected was an M. Night Shyamalan twist ending, involving cheating the space-time continuum via appreciating a good old-fashioned book shelf. Interstellar is the clearest indicator that the director has a social conscience, set on an ecocide-riddled future earth where authorities “don’t want a repeat of the excess and wastefulness of the 20th century.”

After happening upon a secret NASA base, corn farmer and former astronaut Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) barrels into space to find a hospitable planet, by way of shooting himself into a wormhole. The silliness is played straight and heavy-handedly. We don’t blink when we hear lines like “love has meaning, yes” and “time might be another physical dimension.” It’s amazing that this film doesn’t just come across as complete poppycock. Despite Nolan overshooting on almost every level, we mostly go with it—because it has heart and audacity.

7. Insomnia (2002)

The pitch: a neo-noir film based in a town where the sun never sets. There’s no hiding in shadows, no meeting under street lamps. This convention-breaking twist is surely what inspired Nolan to remake the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name. Insomnia is the odd one out in his oeuvre, in that it’s his only film he didn’t write. Al Pacino is rock solid as Will Dormer, a hotshot detective flown into an Alaskan town to deliver cutting insights and psychoanalyse the killer, Robin Williams’ Walter Finch. Williams of course was acting against type. Like in serious movies with Jim Carrey, his performance has an element of “see, I can do this.”

Genre and convention-wise this film is the most hardcoded of Nolan’s work. But it’s not badly made; think of it as elevated procedural. Things intensify when the title activates and the protagonist’s relationship with reality becomes increasingly wobbly. But it never excels psychologically as much as it should…the *gasp*! moment never arrives. This production looks better as a Pacino or Williams film than a Nolan one.

6. Dunkirk (2017)

Of all Nolan’s films, Dunkirk has the strongest sense of humanity. You can feel the director applying a duty of care to this real-life WWII story, which, despite involving a devastating defeat for Allied forces fighting in the north of France, has a ready-made inspirational ending. Trapped on the beach, more than 300,000 British civilians were evacuated—with help from a flotilla of citizen-operated vessels. The beach is introduced early, looking beautiful in a bare way. Some of the film has an impossible Instagram-like sheen, bright and faux-nostalgic. However the colour and vividness fade as the drama wears on.

It’s a curiously adrift war picture. Sometimes it’s where the action is, not when it is. The film is tastefully segmented rather than frustratingly scattered, like Oppenheimer. There’s no clear anchoring performance. Sometimes it’s on the ground, sometimes on the water, sometimes whizzing around with Tom Hardy’s RAF pilot in the sky. Despite or in addition to the sound and fury, the direction is elegant.

5. Memento (2000)

This is the kind of audacious production a blockbuster director makes before they become a blockbuster director. It has the all-in vibes of a balls-to-the-wall debut. The premise: a man who can’t create short term memories—Guy Pearce’s Leonard Shelby—seeks to avenge the death of his wife, in a narrative told in reverse. To help him remember, he takes photos and records notes in the form of tattoos on his body. It’s not just one big mystery for him, but an endless series of small ones.

Guy Pearce’s performance impressively blends steeliness and obstinance with confusion and tumult. He’s like a lot of people: doesn’t want to acknowledge his own vices, even when they’re plain as the nose on his face. This is the sort of highly original film that could never spark a trend—it’s too conceptually niche, too limited. The gimmicky reverse structure paradoxically made me think about cause and effect: how it applies just as much to this film as any other. Despite the clever arrangement there’s not a heck of lot under the hood—but it’s intensely focused and chillingly cerebral.

4. The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

The air in this film is something else. Choked, tortured, combustible. Like the devil has reality in a chokehold. I appreciate that its first set piece is mid-flight, high in the sky, boulder-like sicko Bane (Tom Hardy) doing terrible things tens of thousands of feet in the air. Because that suits the mood: that something high up is going to come down. No superhero movie has felt quite like this. Once Bane blows up the football stadium, about 90 minutes in, all hell breaks loose, triggering a long finale described by the villain as “Gotham’s reckoning.” But really it’s Batman’s.

You can’t beat Ledger’s Joker, certainly not with theatrics. But you can give the villain more purpose, or at least clearer purpose. Unlike his makeup-caked predecessor, Bane doesn’t just want to watch the world burn, he wants social change: an insane combination of anarchist, Marxist and misanthrope. He’s scary in a primordial way.

3. The Dark Knight (2008)

When we first see Batman in The Dark Knight, it’s not really him. This caped crusader is someone else, some random dude in a costume. The real hero apprehends the imposter, who cries foul: “what’s the difference between you and me?” In this moment Nolan makes a more interesting commentary on legend than he did in all of Batman Begins. But when you remember this film your mind goes straight to Heath Ledger, and his amazingly theatrical interpretation of the Joker. Ledger gets the film smoking: every appearance is high voltage, every scene electrifies. “I’m not a monster,” he says. “I’m just ahead of the curve.”

It’s easy to forget that this great villain runs in parallel with the formation of another: Harvey Dent, whose trajectory illustrates a decent person turning foul. He’s got elements of both hero and villain—which is another reason for his name, Two Face. There’s lots of rousing scenes in The Dark Knight, although, like other middle-trilogy classics like The Empire Strikes Back, it has no real beginning or end. But as a collection of scenes, it’s one hell of a showcase.

2. The Prestige (2007)

This is probably the best film ever made about magic—fittingly, with tricks up its sleeve. Nolan’s narrative sleight of hand (which here includes a ripping last minute twist) has never been more thematically relevant. The Prestige is also an amazing film about pursuing greatness and the pitfalls of obsession. It’s about how something you’re totally devoted to can turn you inside out. Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman play feuding magicians in London during the golden age of magic, a spectacular era (what I would give to time travel there…) when large scale illusions were watercooler events.

I love when Nikola Tesla (David Bowie) gives Jackman’s The Great Danton a machine that will revolutionise his act, but leaves a note saying “such a thing will only bring you misery.” Lines like that can sound too neat, but here it works. Nolan dramatises the theatrics of stage magic and adds science or “real” magic to the mix. One interpretation would be to say the former is illusionary, the latter actual. But Nolan’s conclusion is more exciting: both are different kinds of magic. The question of worthiness or unworthiness is entirely dependant on the motivation of the creator or performer.

1. Inception (2010)

Nolan’s magnum opus imagines video game concepts of worldbuilding and level design as matters of the mind, giving Elliot Page’s architecture student Ariadne the mother of all gigs: to “build cathedrals, entire cities, things that never existed, things that couldn’t exist in the real world.” Ariadne’s recruitment leads to a special effects showcase (the famous city bending scene) that feels justified and germane to the story. No heist film had ever been like it, nor any film about dreams. Maybe Inception connected so strongly (the title is now more commonly associated with this movie than the actual word) because it taps into a fear that anything can be stolen—even things deep inside us, under lock and key.

Leonardo DiCaprio’s Don Cobb assembles a team to perform an “inception” on Cillian Murphy’s billionaire energy magnate, penetrating nesting dolls in his consciousness. The pacing of time flows differently in each layer, enabling an exciting kind of cross-cutting. As large and spectacular as Inception‘s images are, Nolan ingeniously ends on a small one: a spinning top. We know exactly the famous final shot means visually, or more to the point what it asks: might “reality” itself be a dream, or a dream within a dream? Edgar Allan Poe’s famous poem got the blockbuster treatment.