20 years on, The Blair Witch Project remains a seminal horror classic

Who could ever forget The Blair Witch Project? That mighty, snotty, movement-defining horror movie turns 20 this year. Travis Johnson retraces the Blair Witch legend, and sees how it holds up.

It’s sometimes hard to differentiate a work from the cultural detritus it accretes.

If something really makes an impact on the collective unconscious, it soon becomes more than the sum of its parts. A film can be quickly reduced to its component parts, meme-ified, repackaged, repurposed. Iconic moments become punchlines, catchphrases, gifs. It gets to a point where its hard to see the original thing through all the parodies, homages, riffs, and rip-offs; going back to the source becomes an act of cultural archaeology.

It’s generally worth the dig, though. It takes genuine greatness to get absorbed into the mass mind; there needs to be something pure, brilliant, and ineffable at the core. So it is with 1999’s The Blair Witch Project: a micro-budget horror flick made by two nascent filmmakers featuring a cast of no-names, that captured the imagination of the world.

Into the Woods with Heather, Josh, and Michael

The plot is simplicity itself: film students Heather (Heather Donahue), Josh (Joshua Leonard), and Michael (Michael C. Williams) decamp to the tiny hamlet of Burkittsville, Maryland, to make a documentary about a local folktale, the Blair Witch. After interviewing a handful of locals about the legend, the trio head into the nearby woods to visit and document a number of locations with ties to the story. And they never come out again.

The formal wrinkle is that the film itself is purportedly comprised of the footage that the three film kids recorded during their trip. Which, as the movie’s marketing spiel told us, was recovered a year after the trio vanished in the woods. This approach grew out of directors Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick’s fascination with paranormal documentaries, with the two then-film students realising that the camera and sound techniques common to breathless tabloid shows about UFOs and Bigfoot could be easily and cheaply adapted to a fiction feature format.

Raising a meagre budget ($60,000 is the official number, but reports vary) and recruiting their three relatively anonymous leads from a pool of 2000 potential candidates, Myrick and Sanchez coached their actors, who were chosen for their strong improvisational abilities, in basic filmmaking techniques. They sent them off with a rough narrative roadmap, a few supplies, and little else, trusting that this approach would yield the cinema verité results they wanted.

Filming took place in Germantown, Maryland; Seneca Creek State Park; and Patapsco Valley State Park. Over the course of eight days the actors traveled from location to location on foot, navigating by GPS and capturing footage along the way. By night, the directors and other crew members stalked their campsites, resulting in the eerie sequences where the three characters react to noises and movement outside their tent.

Filming wrapped on October 31, appropriately enough, and the 20-odd hours of raw footage was condensed down into the lean 81 minute feature that wowed audiences at Sundance and saw the film acquired by Artisan Entertainment for $1.1 million. The Blair Witch Project went on to earn almost $250 million at the global box office.

I Read It on The Internet

We can thank a canny and prescient marketing strategy for that, at least in part. Released at the dawn of the internet, The Blair Witch Project was the first film to really capitalize on the possibilities of the new medium. Countless film fans saw the original trailer for the first time not in the cinema, but over a precarious dial-up internet connection. Many more flocked the film’s website, which carefully presented itself as being about actual events rather than a fictional film. It’s still up if you want to take a look.

Of course, that’s “fake news.” But 20 years ago it was rather charming – the internet wasn’t the roiling cesspool of disinformation and bad faith actors that it is today. Seasoned pop culture mavens were confident that The Blair Witch Project was fiction, but that slight uncertainty, that blurring of possibility, was intoxicatingly piquant. Others bought the lie hook, line and sinker.

The marketing team played into the “I Want to Believe” tendency for all it was worth (it’s worth noting that The X-Files was at the peak of its popularity at this time). The actors were sequestered, with IMDB listing them as “missing, presumed dead”, and flyers begging for any information about their whereabouts being distributed at festivals and screenings.

In a bravura move, a companion documentary, Curse of the Blair Witch, was produced, which treated the film’s elaborate mythology as recorded folklore. This kind of “in universe” document is a fairly common marketing tactic now, but at the time, if it wasn’t entirely new, it was at least never done so elaborately and seriously. Two other mockumentaries, Sticks and Stones: An Exploration of the Blair Witch Legend (1999), and The Massacre of The Burkittsville 7: The Blair Witch Legacy (2000), were also released to coincide with the original film’s VHS and cable release, respectively.

21st Century Witch Craze

The Blair Witch Project’s intricate but compellingly shaggy backstory was a big selling point, incorporating colonial history, Christian superstition, pagan symbolism and the relatively modern serial killer phenomenon. Acolytes were invited to dive deep into this seemingly random but carefully constructed hodgepodge of occult lore, true crime, and historical records, piecing together their own theories. A tie-in book, The Blair Witch Project: A Dossier, written by “noted paranormal journalist” D.A. Stern in the same “it’s all real” style as the bulk of the marketing material, explicated the canonical lore.

They were only the beginning. The Blair Witch Project went on to spawn two sequels: the poorly received Book of Shadows: the Blair Witch (2000), by noted documentarian Joe Berlinger, and the considerably more highly regarded Blair Witch (2016) by Adam Wingard. It was initially marketed as an unconnected horror movie, The Woods, before the project’s true nature was revealed.

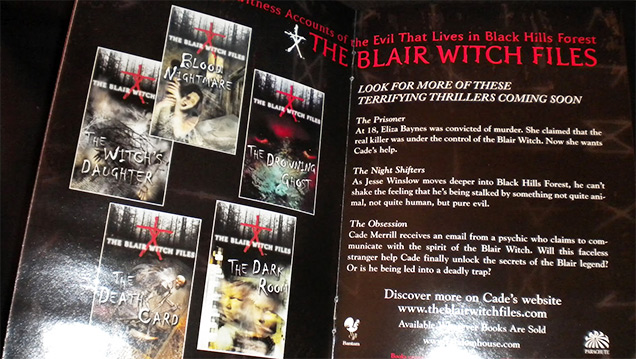

Outside of cinema, the Blair Witch cult spread its dark influence through other media: a number of tie-in comic books, several novels (including an eight volume young adult series, The Blair Witch Files), a trilogy of video games, and even an action figure (although the Witch is never depicted in the film, the figure was touted as an “artist’s impression”). Myrick and Sanchez are apparently currently working on a television series to further expand the property.

Found Footage Phenomena

Beyond the actual franchise the most obvious shadow cast by the Blair Witch was the sudden and still-current popularity of the “found footage” format. Of course, The Blair Witch Project wasn’t the first film to use the conceit – Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust beat it by 19 years, for one thing – but it certainly cemented the form in the public consciousness.

A slew of imitators sprang up in the films’ wake, with creators inspired by the style’s immediacy and visceral impact, and producers attracted to the perceived affordability of using consumer-grade equipment, real-world locations, and semi-professional actors (the technical challenges of papering over the cracks in ostensibly real footage would prove a significant hurdle for many). Most are risible, a few are inspired.

The most successful, Paranormal Activity (2007), spawned a franchise more successful than The Blair Witch Project’s own, while the past decade has seen more and more found footage films go beyond the boundaries of straight horror. Consider the kaiju picture Cloverfield (2008), superhero origin story Chronicle (2012), and domestic thriller Searching (2018).

The Horror, The Horror

Yet The Blair Witch Project endures, and will continue to endure. Not because of any neat formal tricks or bold marketing, but because it is simply a great horror movie.

Looked at again now, with the gift of distance from all the hullabaloo, the film is stark and merciless, resolutely going about the business of tightening the supernatural knot around its three hapless protagonists until their inevitable doom is visited upon them. It makes a merit of its limitations, never showing the titular threat (what was true for Jaws is even truer here) and instead letting the viewer populate the pitch-black night and shadowed woods with whatever nightmares we can conceive.

In Donahue, Leonard, and Williams, the film has a central cast who bring sublime believability and pathos to their roles. It may have been parodied into the ground, but Heather’s tearful, runny-nosed to-camera confession remains one of the most indelible images in horror history. Tonally, the film is in a class of its own, enveloping the viewer in a rising sense of creeping dread and uncanny horror. While the films it inspired may not inspire us, and its fortunes as a franchise are varied, the purity of the original exercise ensures that, now and forever, the Blair Witch continues to lurk in the lonely woods outside Burkittsville.