Jirga is a mesmerising Afghanistan-set drama exploring the consequences of war

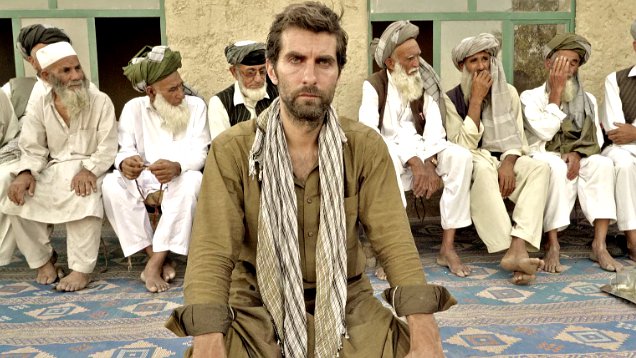

Writer/director Benjamin Gilmour’s Jirga is an arresting drama about one man’s journey for penance, even it means that he’ll pay for it with his life. Sam Smith plays Australian soldier Mike Wheeler haunted by the death of a man during a village raid (by his hand) and fixed on finding his way back the village to beg forgiveness.

Smith’s performance as Wheeler is one defined by the strange echoes of his inner torment, reverberating through this stunning Afghani landscape. Desperately navigating being followed through Kabul, struggling to remain upright through perilous gorges avoiding Taliban guerrillas, and striding over endless baron landscapes with the harsh sun hammering down, Smith’s blind determination as Wheeler is mesmerising.

Gilmour, who also acts as the cinematographer, shoots the arid beauty with stillness and admiration. There’s a beautiful moment when you’re trying to make out Wheeler’s cab transport against the shale hills. The road feels like they’re camouflaged alongside the natural seams in the countryside. In a brief oasis moment in the film, Wheeler is led to Band-e-Amir by his Taxi Driver (the warm musical character played by Sher Alam Miskeen Ustad).

Gilmour’s detour to this sublime blue lake surrounded by stone canyons is a defining moment for Jirga. Gilmour takes the philosophical Terrence Malick ‘Thin Red Line’ approach to a war film, rather than Steven Spielberg’s classical heroism in Saving Private Ryan. Though an exchange between Wheeler and the son of Atta Ullah (an unforgettable Inam Khan) – the man Wheeler killed – has the impact of the untimely death of Adam Goldberg’s Private Mellish in Private Ryan.

Jirga means tribal council. In the process of coming to this task Gilmour’s script ask questions; something that this critic can’t recall ever featuring in another Australian war drama. During Wheeler’s voyage he is captured (and released). He encounters Afghani people who reinforce that, firstly, this journey is folly, but most importantly that they aren’t really able to distinguish an Australian from an American.

For those tribal people, it’s just another westerner determined to keep them in a perpetual state of oppression or occupation. Jirga gets a chance to challenge audiences to contemplate equal moral culpability as our U.S allies for the state of the country.

AJ True’s score is littered with elegant Afghani string arrangements critical to Wheeler’s journey. However, I was most moved by brief, brassy, melancholic notes reminiscent of Brad Fiedel’s iconic score for Terminator 2: Judgement Day. This is not a portrayal of Afghanistan as an irreparably damaged battlefield; quite the contrary. There’s a yearning in those notes for judgement on an intensely personal level.

In 1967, the Boxing Heavyweight Champion of the World Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted for the Vietnam War. The sporting hero turned activist said this statement: “No, I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation…” This once radical statement feels right on time. Jirga revisits the cost of war and discusses who is willing to pay for the consequences.